We were raised by Puffins. With three TV channels and no internet, for long stretches of our lives reading was the best (and sometimes, the only) way to pass the time. Here we return to the books that made us and analyse what makes them great.

Preface

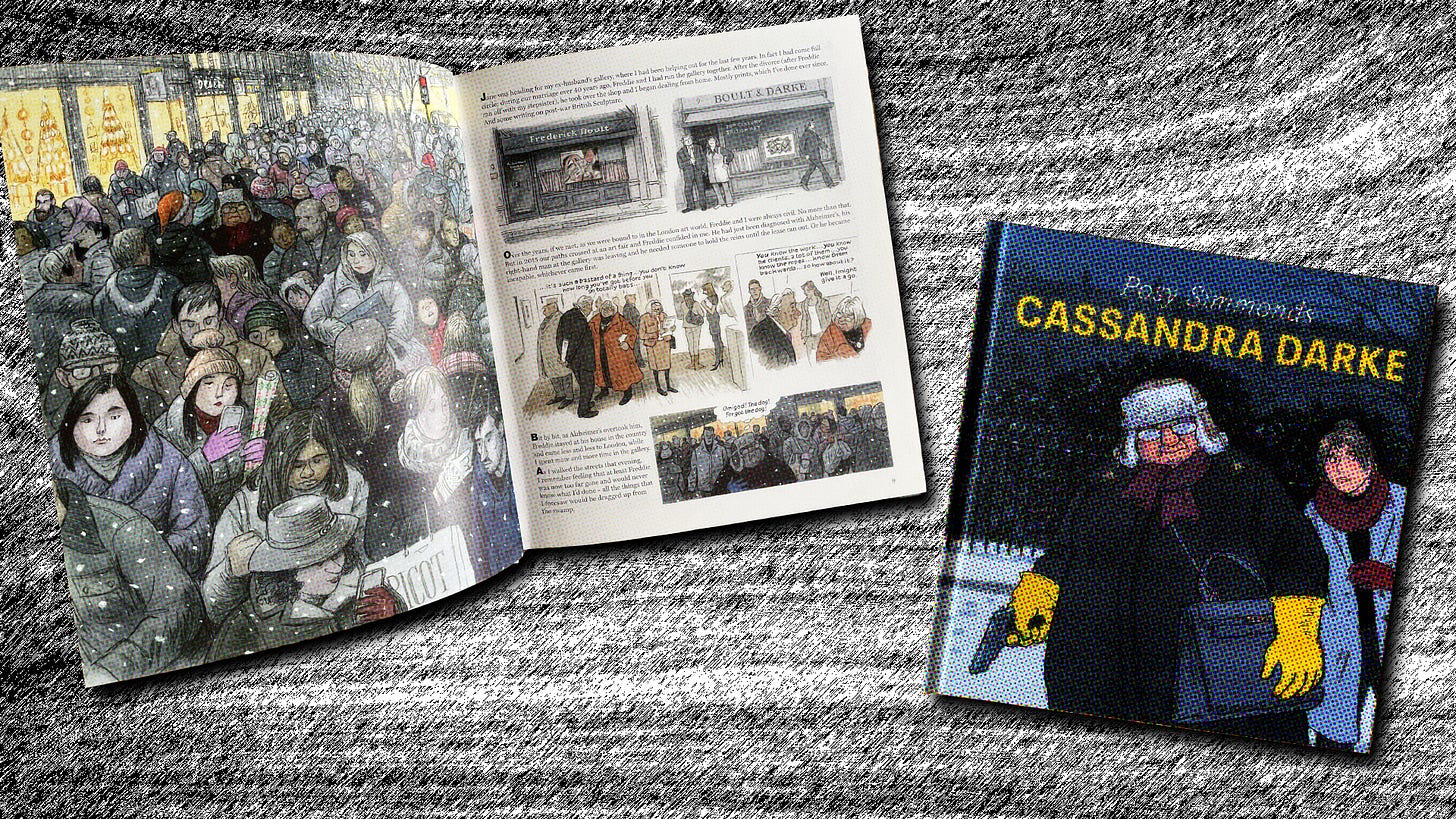

A graphic novel by celebrated Guardian cartoonist Posy Simmonds, Cassandra Darke is a Scrooge-ish take on London’s contemporary beau monde. The book opens on a snowy city during Advent; art dealer Cassandra Darke is in disgrace after being convicted of fraud, and briefly considers suicide in the solitary splendour of her Chelsea townhouse. (Simmonds, who knows her audience, finds an elegant way to tell us that the house is worth £8 million.) Then a mysterious break-in draws her into the murderous activities of a criminal gang, giving Cassandra a shot at sororal solidarity and redemption.

Chapter 1: A book for children

There is a moment, in the days leading up to it, when Christmas floods over the borders. Up to this point, Christmas is essentially an optional activity; after it, you will be pulled into the festive machinery whether you like it or not. The transition is marked by a sudden settling. Schools and offices close their doors, the streets are quiet, and you can get any table you like in West End pubs.

At the last Christmas overwhelms the infrastructure, like an extreme weather event or Godzilla. One Christmas Eve afternoon in the early ‘90s, when my brother and I were setting off for a pub in the nearby town, the station manager - who had known us for years, and had justifiably concluded that we had no idea how the world worked - warned us not to miss the last train back; ‘the service starts to run down at 6pm’. On the deserted platform carols were playing quietly over the tannoy. As we waited I had a dreamy vision of the last few trains moving around south-east England, their windows shining in the dark, delivering solitary travellers at each station before running empty to the depot.

I love these moments when Christmas gets into the mechanism and imposes itself on ordinary things: the ordinarier, the better. When I was a kid I used to count the days until December 24. You might think there’s nothing so unusual about that, but I started counting on January 1. It was a long, lonely, lunatic enterprise, and even as a child I knew there was something unhinged about it. But in mid-December my furtive obsession was validated as everyone else started to get sucked into the machinery. Signifiers began to appear in otherwise sensible, grown-up contexts: holly motifs on the foil tops of milk bottles, the BBC Christmas idents, the illuminated sleigh that was towed around the residential streets of Mortlake by the local Rotary Club.

The places where Christmas intersects with the real world are at the heart of Raymond Briggs’s Father Christmas (1973), which was everywhere when I was a child. (Briggs’s The Snowman was published in 1978 and wasn’t adapted for TV until 1982, which meant it missed my Proustian window.) Father Christmas is an animated account of the man himself’s Christmas Eve schedule, but the conceit is that Father Christmas is an ordinary man for whom everything is an enormous ball-ache, from waking up (‘BLOOMING CHRISTMAS HERE AGAIN’) and pushing the sleigh out of the shed (‘WORK, WORK, WORK!’) to fighting his way down narrow chimneys (‘BLOOMING SOOT!’). This is Father Christmas as a harassed functionary in the service economy, grumbling about his shift pattern and looking forward to his pension. He eats a meagre packed lunch on a snowbound suburban rooftop and gets irritably jammed in an Aga. As dawn breaks, he crosses paths with a laconic milkman: ‘Still at it mate?’ ‘NEARLY DONE.’

Father Christmas would not be such a perfect book without its humdrum houses, monotonous scrubby landscapes and professionally frustrated main character. Here is the emotional appeal of Christmas, for me at least: the transubstantiation of the everyday that takes place during a short ethereal period in the deep stretch of the year.

I don’t read many graphic novels, and I’ve no idea whether Posy Simmonds is often compared to Raymond Briggs. I do know that Simmonds is most usually described as the chronicler of the urban middle classes, for which she has attracted a certain amount of disparagement, whereas Briggs’s work centred working class people in explicitly straitened contexts. (Father Christmas has an outdoor lavatory.) But in their close, affectionate observation of cussed, workaday English lives, they seem alike to me.

Cassandra Darke is full of the moments when Christmas floods over the borders and intersects with everyday things. Here are the reasons I get it down from the shelf at the beginning of December every year: a perfectly rendered Big Issue seller outside a snow-covered Burlington Arcade in Piccadilly. In the middle of a row of identical grey townhouses, there is one that is ablaze with Christmas decorations. A huddled smoker stands under a swagged garland decorating a Victorian pub. A huge full-page panel shows a great grey crowd of shoppers on Oxford Street, cramped and pissed off, staring at their phones as they shuffle along; but disappearing into the distance there are two people wearing Santa hats.

Chapter 2: A book for adults

Cassandra Darke has a lot of fun with the middle classes and particularly with the London art world, a world that Simmonds presumably knows pretty well (‘Francis Bacon? Once an interior decorator, always an interior decorator’.) The nature of life in the underpopulated posh streets of Chelsea, where houses are investments rather than homes, is captured in a tiny throwaway panel that renders a mother’s remark to her child in Cyrillic script.

But Simmonds’s long tenure at the Guardian didn’t happen by accident, and she is also perfectly at home with the passionate activism of Dickens’s story. One sequence of panels shows the Christmas trees that light up the street-level lobbies of corporate offices all across London in December. Every Londoner knows the antiseptic perfection of these trees, decorated to convey core brand values and whatever measure of festivity is commensurate with the Q2 figures. If you walk down certain streets in the City - the streets where Scrooge had his counting house - it is as though the season has been disembowelled and embalmed. As Darke says, each atrium has ‘a Christmas tableau, the components as fixed as those of a crib scene: tree, reception desk, giant vase, someone keeping watch by night.’ (It would not have occurred to me to notice the giant vases, but Simmonds is absolutely on the money.) These ‘someones keeping watch’ in Cassandra Darke, as in real life, are all minority ethnicity Londoners in uncomfortable formal suits, and the Christmas atrium panels are followed by a matching set showing people sleeping in cardboard boxes outside the warming air vents.

As is the way with Scrooge-ish characters, Darke is magnificently unpleasant, selfish and solitary. Simmonds is very good at nasty characters, as she showed through her ‘Posy’ cartoons in the Guardian; she has the thin streak of brutality that makes everything a little bit more interesting. In an interview with her old paper to publicise her 2010 graphic novel Tamara Drewe she talked about ‘lulling the spouse’, a tactic she dreamed up and placed in the mouth of one of her characters, the inveterate philanderer Nicholas Hardiman:

‘Behind it is the idea that to avoid suspicion, you must first arouse it,’ Simmonds laughs. ‘So you tell the spouse, rather unconvincingly, that, unexpectedly, you're going to be very late this evening and you'll be at mutual friend X's house. And then you actually are at X's house when the anxious spouse rings up, which rather puts them off checking up on you again for a while.’

I find this kind of deviousness quite frightening, but her capacity to inhabit the minds of cunning, manipulative people adds greatly to the appeal of Simmonds’s work. It’s a particular boon when it comes to to re-inventing Scrooge, who tends towards cartoonishness in less capable hands. Darke is convincingly appalling, careless of her housekeeper (‘heavy-handed with the dill’), her office junior (‘I haven’t much sympathy’) and homeless people (‘Got any spare change?’ ‘Yes thanks.’) But as Dickens did with the original Scrooge, Simmonds also shows us all of the ways the world has been unkind or disappointing to Cassandra, an ageing and overweight woman who has been cursed with a plain face and an unusually good brain. We’re also shown some of the things that make her likeable and even admirable, not least her furious refusal to lie down and take punishment, her self-sufficiency and her doughty courage, all of which she shares with Scrooge.

Some of this is conveyed subtly using Simmonds’s signature talent for drawing gestures and facial expressions. A faintly sketched passer-by is wordlessly disgusted by Darke’s bulk; beauteous young things have pity and contempt written all over their faces. At other times, key information about character and mores is delivered with miniature precision in the text, which is frequently extremely funny. When - for plot reasons - Darke receives a text message intended for someone else that reads ‘Break your fucking legs that’s a promise cunt’, she notes ‘I immediately assumed the message had been sent by a friend and fellow art dealer, Teddy Wood, during one of his benders.’

One brilliant panel about halfway through shows Cassandra slumped on the sofa. She has just overheard her young lodger having passionate, noisy sex. Her body is overflowing the seat cushions. Her head is down, and her jowls bulge around the thin, tense line of her mouth in a way that overweight ageing women will recognise with horror. The text narrates what she is thinking about:

I remember sitting overwhelmed by regret. It was the realisation that my diffidence in sexual matters had been just cowardice, the fear of losing control. I had denied myself pleasure.

This is Simmonds’ answer to Scrooge’s agony at the memory of his lost love. Rarely has A Christmas Carol been translated so thoughtfully to a contemporary context. Simmonds might usually be cast as the chronicler of the middle classes, but what is less often noted is the most Dickensian attribute of all, and one that underpins the message of A Christmas Carol: her abiding generous interest in human beings.

For more graphic storytelling, try our piece on Los Bros Hernandez and their version of Dean Motter’s underground comic Mr X: