The Return of Mister X

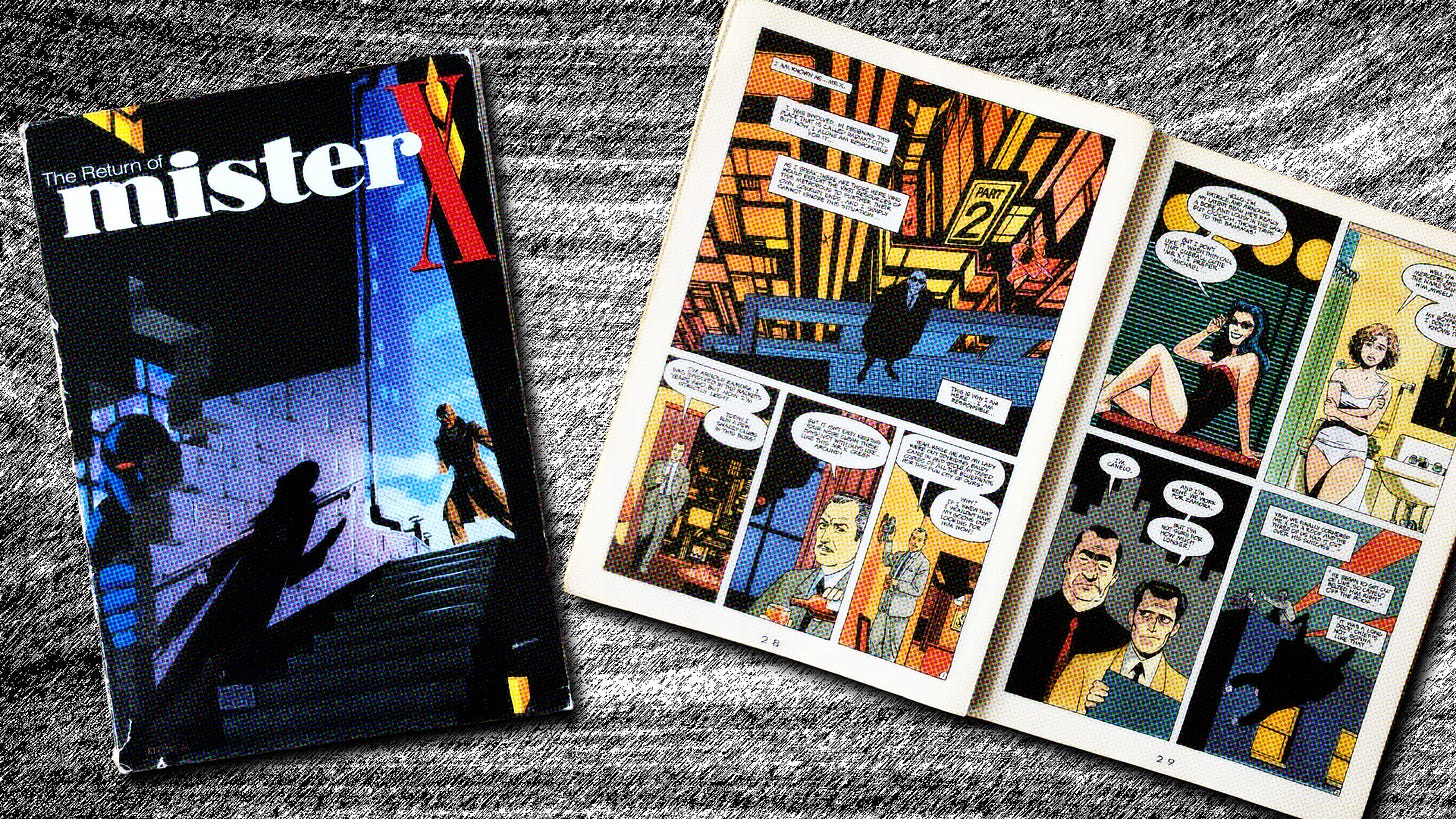

Dean Motter / Gilbert, Mario & Jaime Hernandez (1986, Titan Books)

We were raised by Puffins. With three TV channels and no internet, for long stretches of our lives reading was the best (and sometimes, the only) way to pass the time. Here we return to the books that made us and analyse what makes them great.

Preface

Radiant City was supposed to be the city of the future, with revolutionary architecture engineered to make its citizens happy and fulfilled, but the developers cut corners on the materials and now it is a dark metropolis that drives its inhabitants mad. Only the mysterious Mr X, who stalks the shadows in his billowing overcoat and wraparound sunglasses, seems to have a plan to save the city.

The Return of Mister X is a comic with a fraught history. The title makes it sound like a sequel but Mister X was not, in fact, returning; he had barely arrived in the first place. The character was created by Dean Motter, who then worked with artist Paul Rivoche to build out his fictional world, in the process creating a series of stylish and intriguing posters that caught the attention of the comics world and drove up anticipation for whatever it was they were producing. Unfortunately they produced nothing.

In the end new young comics stars Los Bros Hernandez - three Mexican-American brothers best known for their comic Love and Rockets - were brought in to get the comic rolling. The produced an initial four issues that were then packaged together as a paperback.

None of which I knew when I wandered into Mega City Comics in Camden in 1986 and saw the book on the shelf. I vaguely assumed that it had something to do with the track ‘Mr X’ on Ultravox’s 1980 album Vienna, and maybe it did, somewhere back in the mists of inspiration (the figure in the song certainly seems reminiscent of the character in the comics, and Motter knew his New Wave music). I was grabbed by the same things that had grabbed everyone about Rivoche’s posters: the soaring, neon, Deco city, the Expressionist shadows, the mysterious bald man in the coat and shades. I bought it immediately.

What I discovered in the book was not so much the character or the story but the artists, particularly Jaime Hernandez, who did the bulk of the art and whose own comics - the stories of the fraught love-lives of LA punks Maggie, Hopey and all their friends - were about to become one of the great and abiding joys of my life. If Mister X achieved nothing else, he improved my comics collection immensely.

Contents

The Return of Mister X is coloured (by Rivoche himself, along with Klaus Schönfeld) but Jaime Hernandez mostly works in black and white and he has a confident, dynamic line even here. There is something of the European clair ligne approach of Hergé’s Tintin, but with the bravado of an American comic book by Jim Steranko or Jack Kirby. The backgrounds are full of detail, the characters full of life.

Those people are most notable - his ability to capture a sense of an individual in movement and thought, their postures in the drape of their clothes, their expressions flitting across the faces. The book is full of teeming streets and packed parties and every person that appears is distinct and recognisable.

All this is helped by his incredible range, switching from detailed, subtle portraits like something from Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon or Byrne Hogarth’s Tarzan to the exaggerated emotion and energetic action of cartooning like his hero Hank Ketchum (Dennis the Menace - the anodyne American one, not the sublime agent of chaos in the Beano).

The plot is mostly concerned with Mr X returning to Radiant City and trying to regain the plans that will help him fix his marred creation, setting up characters and clearing the decks for future adventures. The Hernandez brothers instinctively try and add in a romantic subplot but they can’t quite pull it off; they haven’t yet reached the emotional depth of something like Jaime Hernandez’s The Love Bunglers (2014), a book that still reduces me to tears every time I read it.

The story zips by, an enjoyable mash-up of film noir and 50’s ‘googie’ atom-age futurism, all gangsters and robots, exotic nightclubs and flying cars, but it’s ultimately as flimsy as the sub-standard construction of Radiant City itself.

Afterword

…but the concept: the concept is simply terrific. An obsessive architect develops a serum that stops him sleeping so he can devote all the time to realising a vision undercut by penny-pinching developers. That alone is the sort of ludicrous story premise which is only really possible in comics.

Indie comics in the ‘80s had an energy and a role reminiscent of the punk and New Wave music artists that Motter and the Hernandez brothers adored. Like a band, and unlike TV or film, comics allows an individual, or a small tightly knit group, to work intently and personally on their own mad projects, yet still produce something that can stand - with equivalent production values - against the mainstream.

From a European perspective, The Return of Mister X fitted perfectly into this sense of radical, alternative comics. While the US market was still dominated by superheroes, as a British kid I had grown up on Hergé’s Tintin and the French sci-fi psychedelia comics of Moebius, and the home-grown anarchy of The Beano and the punk dystopias 2000AD.

Indeed this defiant weirdness was about to infect American mainstream comics as 2000AD writers like Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman and Warren Ellis crossed the Atlantic and started working on comics for DC and Marvel, changing superheroes forever. (There’s a good argument that you don’t get the Marvel Cinematic Universe without 2000AD, but that’s for another day.)

But more than just the concept, the image. Those Paul Rivoche posters, the cover that caught my attention, the neon canyons of the mid-century utopian city, the airships in the sky and the crowded streets below, the mysterious man, his expressionist shadow falling across the rooftops. It is an image composed of pure pulp, and as such overshadows its own story.

The image is, itself, in the lineage of great pulp images of the past. The famous portrait of Pierre Souvestre and Marcel Allain’s Fantômas (1911), the master criminal in opera coat and domino mask, leaning out over the skyline of Paris, bloody knife in hand. The cover of Detective Comics #27 (1939), as Bill Fingers’ Batman swings in over the roofs of Gotham City for the first time. Of Conrad Veidt’s Somnambulist in The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) and a chiaroscuro Sam Spade (Humphrey Bogart) in The Maltese Falcon (1941).

It is an image that transcends and eclipses its own origins as so often happens with pulp fiction. These images take on a life of their own, casting long shadows across the culture that follows them. Just as Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter of Mars and Tarzan influenced both Superman and Batman and set patterns for so much of superhero fiction to follow, or H. Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines carved out of Imperialism the tropes that in time brought us Indiana Jones, so Mister X is namechecked by Terry Gilliam in the creation of Brazil (1985), by Tim Burton in his Batman films, and by Alex Proyas in his Dark City (1998).

In some ways, part of the real joy of a comic like The Return of Mister X is in its imperfections and its failings. Where it succeeds it is wonderful, allowing us to enjoy the Los Bros Hernandez’ extraordinary skills at visual storytelling. However, where it fails, it inspires: it hands us imagery and settings that incite our own imaginations, invite us, like Mister X himself, to build our own glittering and shadowy Radiant City.

For more from the same underground ‘80s L.A. that brought us Los Bros Hernandez, you could do worse than Alex Cox’s Repo Man

Thanks, Mark, much appreciated - as is the recommendation - I hadn’t even heard of it and now I very much need to find it

The tone of this one is so, so earnest. What happened to the playfulness of the earlier essays?