We were raised by Puffins. With three TV channels and no internet, for long stretches of our lives reading was the best (and sometimes, the only) way to pass the time. Here we return to the books that made us and analyse what makes them great.

Preface

In which we are introduced to Winnie-the-Pooh, a Bear of little Brain, who lives in the Hundred Acre Wood with his friends Rabbit, Owl, Tigger, Kanga and Roo, and most of all Piglet and Christopher Robin. With all of whom he variously has adventures, makes up songs and eats an awful lot. Oh, we left out Eeyore; but then again everyone always does, you know.

Let us be clear from the get-go: we’re talking here about ‘Winnie-the-Pooh’, who has hyphens and is drawn by E. H. Shepherd, not ‘Winnie the Pooh’, who has no hyphens but does have a little red shirt, the voice of Sterling Holloway and animation courtesy of the Walt Disney company. Pooh wouldn’t be rude about the American cartoons; he’d just pretend he hadn’t seen them, and so we shall do the same.

The Pooh of the book arrives coming downstairs backwards (the only way he knows), his head bumping on each step as Christopher Robin drags him along behind him. It’s a delightfully meta introduction. Milne introduces us to fictionalised versions of himself, his son and his son’s toy, before creating a series of fictions within the fictionalised world. Christopher Robin himself gets confused about what’s real and whether he really remembers the events Milne relates:

‘I do remember,’ he said, ‘only Pooh doesn’t very well, so that’s why he likes having it told to him again. Because then it's a real story and not just a remembering.’

Pooh himself had quite a complicated beginning involving two bears – one real, one not – and a swan. There was a real bear called ‘Winnipeg’, who was bought at an Ontario railway station for $20 and became the mascot of a Canadian Cavalry Regiment before being left at the London Zoo during the First World War. There was a soft toy bear called ‘Edward’, who belonged to Milne’s son Christopher Robin. And there was a pet swan called Pooh. Christopher Robin was fond of both the real animals and so changed the name of his toy, with a ‘the’ in the middle, and we all know what that means.

Anyhow. Here he is at the bottom, and ready to be introduced to you. Winnie-the-Pooh.

When I first heard his name, I said, just as you are going to say, “But I thought he was a boy?”

“So did I,” said Christopher Robin.

“Then you can’t call him Winnie?”

“I don’t.”

“But you said -”

“He’s Winnie-ther-Pooh. Don’t you know what ‘ther’ means?”

“Ah, yes, now I do,” I said quickly; and I hope you do too, because it is all the explanation you are going to get.

Contents

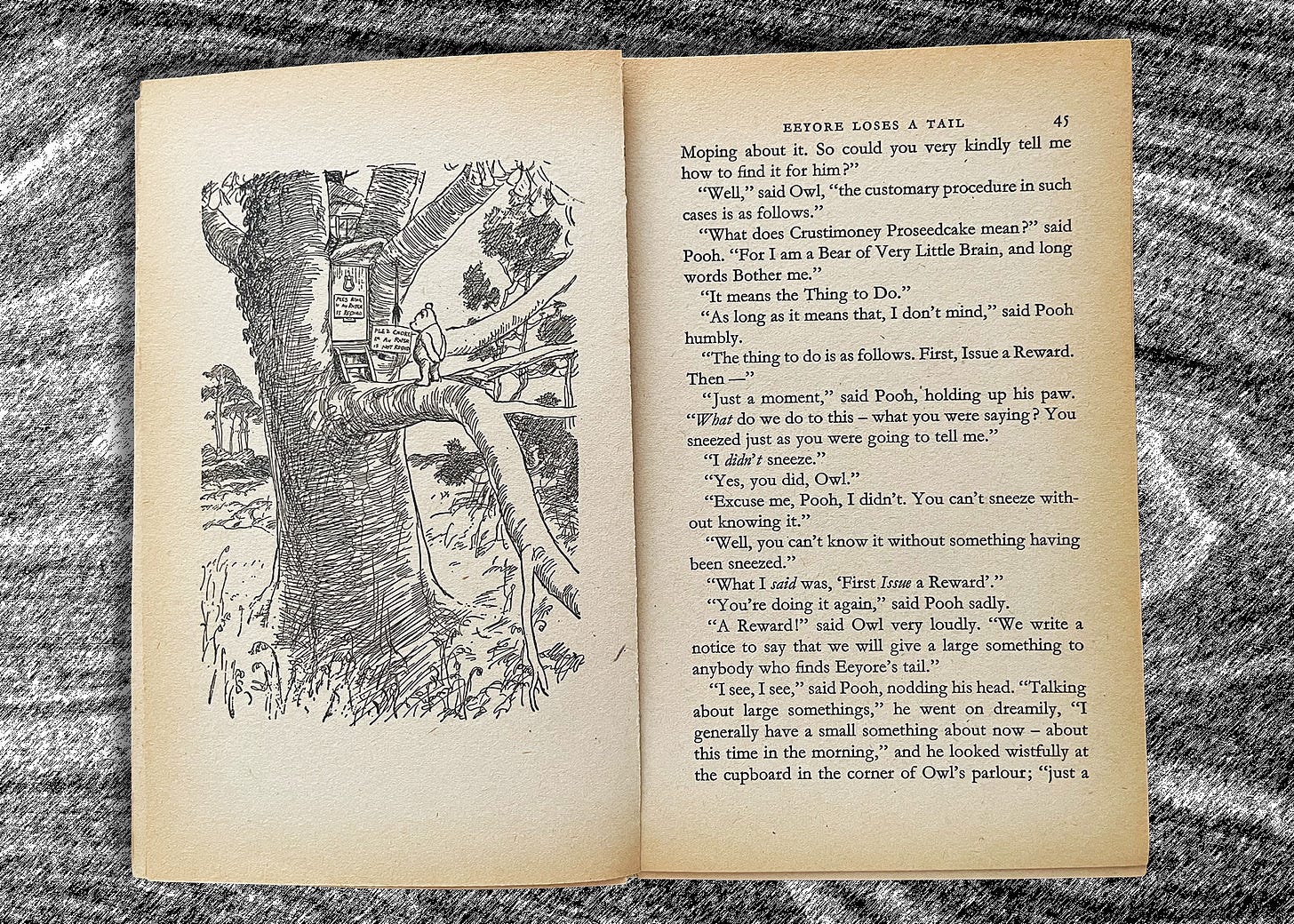

The main character might have had a complicated backstory, but the stories themselves are deceptively simple. ‘Deceptive’ because they are craftily plotted. Before Pooh, Milne had written a serialised detective story The Red House Mystery, and the Pooh stories share this ‘fair play’ mystery approach. In ‘In which Pooh and Piglet go hunting and nearly catch a Woozle’, Milne shares all the clues to what’s happening in the description; once you know Pooh and Piglet been following their own footprints in the snow, you can go back and re-read the chapter and see it all unfold in front of you. In ‘In which Eeyore loses a tail and Pooh finds one’ E. H. Shepherd joins in, clearly showing us [spoiler] Eeyore’s missing tail hanging up as Owl’s bell-pull in a full-page illustration. If we’ve looked at the pictures on the cover, we’ll know what’s happened even before Pooh figures it out.

And this isn’t the only writerly craft on display. One of the reasons Winnie-the-Pooh has endured is that it is genuinely funny. It is quite hard to make a solitary reader laugh out loud, but rereading the stories for this piece I laughed at least once a chapter.

Milne wrote often for Punch, the ‘humourous’ periodical, and he has the poised comic prose style of Jerome K. Jerome and P. G. Wodehouse and any number of other early twentieth century comic writers with decorative initials in their names. He is chatty and informal, lending himself perfectly to being read aloud. Most importantly he doesn’t spare his stylistic flourishes for the sake of the children. Pooh’s antics – rolling in mud to disguise himself as a cloud and then floating up to a beehive on a sky blue balloon – are amusing, but they are then related with wit and perfect timing.

The bees were still buzzing as suspiciously as ever. Some of them, indeed, left their nests and flew all round the cloud… and one bee sat down on the nose of the cloud for a moment and then got up again.

‘Christopher - ow! - Robin,’ called out the cloud… ‘I have just been thinking, and I have come to a very important decision. These are the wrong sort of bees.’

How beautifully structured that joke is. Milne never tells us Pooh is stung on the nose by the bee; he allows us to construct it for ourselves. Then he finishes it with Pooh’s dissembling, his desperate covering of his own terrible mistake. That arch, sophisticated Punch tone lends itself perfectly to the daft adventures of Pooh and his friends.

It is also a style honed on the niceties and awfulness of the British social structure, as much of that early twentieth century comic writing was. The occupants of the Hundred Acre Wood are recognisable British middle class types: the community bossy boots Rabbit, the bumptiously hearty Tigger, the petit-bourgeois striver Piglet. However, they are also all, recognisably, children. There is little moralising; few lessons are learned. Yes, the animals are best friends, but they are also instinctive ego-maniacs in the way that small children are, mostly focussed on what they want and all vying for the affection of Christopher Robin, in the way that siblings vie for parental affections or villagers for a kind word from the squire.

This is, of course, another key to the stories’ longevity. We all recognise that experience, just as we recognise the characters. We all know a self-appointed know-it-all like Owl and a moaning cynic like Eeyore, whose misery is pure self-aggrandisement. We all identify with Pooh, the gentle, self-effacing and much-derided bear of little brain who is nonetheless the only person who ever gets anything done around here, and is definitely the one Christopher Robin loves the most.

Afterword

Winnie-the-Pooh is a ‘classic’, which is a curse as much as an honorific. Classics are set up to be knocked down or, worse, confined to a display case in a distant gallery where they might be stumbled upon only by the most diligent browser.

The narrative of art since Modernism has been one of rolling revolution, the lone Bohemian genius upending the staid strictures of the Academy to produce never-ending novelty. The classics are there to be kicked against; how can one be an iconoclast without icons to deface? The classics of the previous generation must become the deluded follies of the temporally disadvantaged.

One of the salutary bits of growing up is the discovery that classics are often classic for a reason. The Seventh Seal isn’t a pretentious piece of European pseudo-intellectualism; it’s a moving cinematic exploration of life, love and death. Rembrandt wasn’t a painter who produced pictures of crinkle-faced tramps in a brown Windsor fog; he was a magician who could conjure human souls from paint and fold time to carry them down the centuries. Dickens’s novels aren’t grinding slogs; they are encapsulations of a whole city, full of teeming, various, sad and hilarious humanity.

Experiencing the classics matters because classics are integral to the culture. Through being read and thought about and esteemed, they have become influential and important. Knowing them is key to understanding one's culture, enabling you to decode assumptions and references. If you have a little familiarity with Greek myth and Bible stories, suddenly all the paintings in an art gallery make more sense.

But it’s also important to consume the classics because they are very good, often in a way that defies their reputation. Winnie-the-Pooh is not the syrupy, cosy collection of bedtime stories that Disney animations and toys and duvet covers might suggest. Or rather, it is not only that. It is also funny, wise and sometimes startlingly astringent. It manages to be both justly sentimental about childhood and admirably clear-eyed.

In the final story of the second book of stories, The House at Pooh Corner, Christopher Robin is going away to school and says goodbye to the animals. He knows he will not be allowed to do ‘Nothing’ in the woods with his friends any more. He and Pooh go up to their favourite spot and Christopher Robin makes Pooh promise to visit it when he has gone. As a child who went away to boarding school myself I find this sequence unreasonably heartbreaking, and just writing this paragraph has used up all the tissues in the house.

We all have to leave the Hundred Acre Wood. We have to grow up and stop doing Nothing. But it is reassuring to know that Winnie-the-Pooh is still up there on the shelf, keeping one tiny slice of childhood safe for us.

For more childish humour, there’s always the Crack-a-Joke book:

“One of the salutary bits of growing up is the discovery that classics are often classic for a reason.” Too true!

And thank you for bringing a tear to the eye of this American who only knows the red-shirted Pooh. I will put the books on my to-read-out-loud-to-the-kids list ASAP (we’re engrossed in Tom Sawyer now).

Oh my, I guess this is the forum to admit that not only did I read the the original Pooh stories to my children, made them memorize ‘Halfway Down the Stairs’ and also quiz them regularly on their memory (they are now 22 & 20 yrs old) but I also take down one of the books, with some regularity, and read a bit just to me…especially when I get a little lost in the adult world...