We were raised by Puffins. With three TV channels and no internet, for long stretches of our lives reading was the best (and sometimes, the only) way to pass the time. Here we return to the books that made us and analyse what makes them great.

Preface

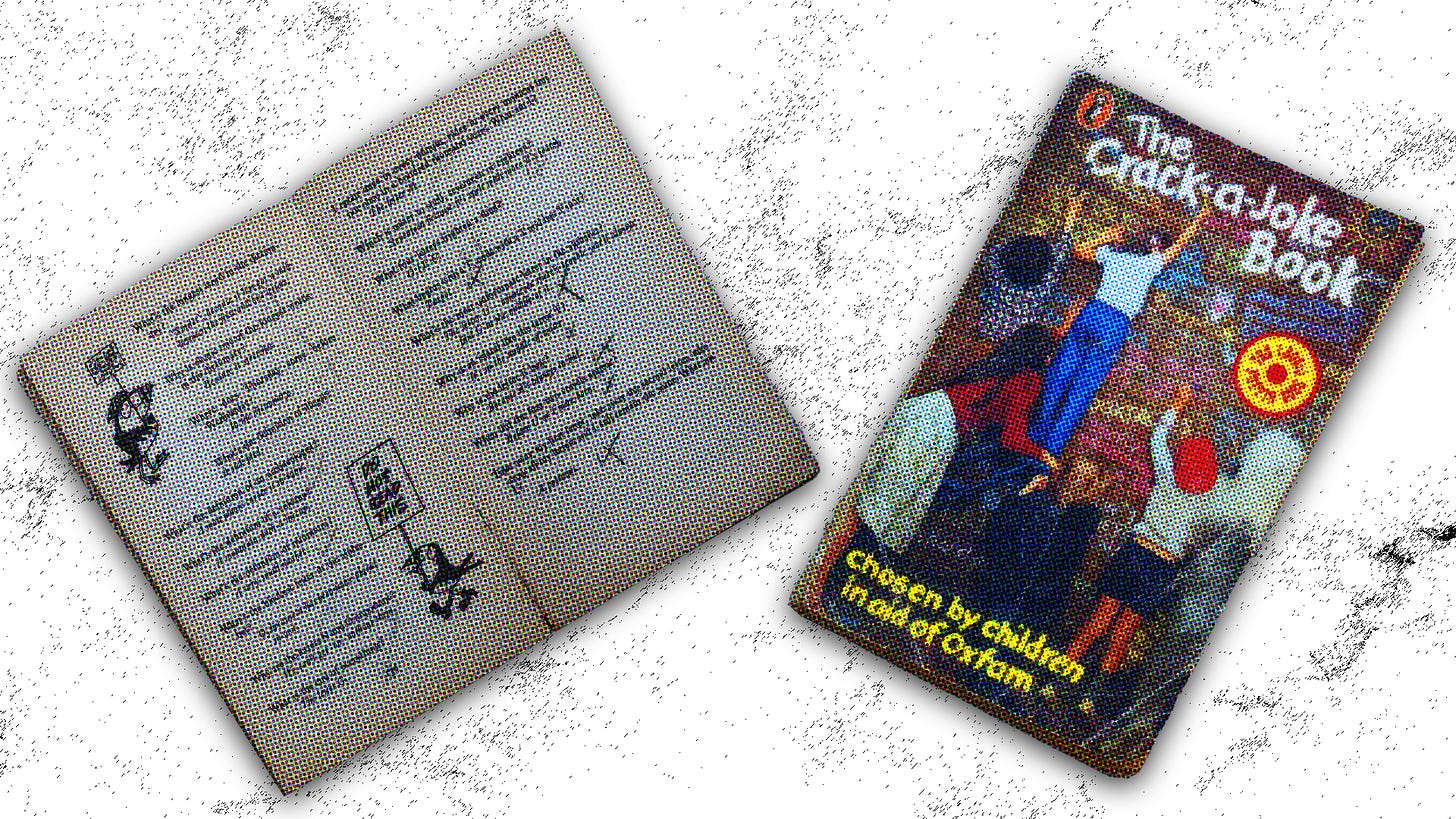

Literally just a compendium of hundreds of child-appropriate jokes, loosely organised by theme and interspersed with cartoons of puffins.

What comes out of the wardrobe at a hundred miles an hour?

Stirling Moth.

The Crack-a-Joke Book was published by Puffin, Penguin’s legendary children’s imprint, and was a fundraising exercise for Oxfam back when giving money to Oxfam was an entirely morally uncomplicated business. It is heavily implied that the jokes were all submitted by children and there is a hall-of-fame list of child contributors at the end (‘Tina Sheppard from Wantage’). However, Graeme Garden, Bill Oddie and Tim Brooke-Taylor were all editorially involved and - with a weary adult cynicism that would have got us kicked out of Kaye Webb’s office - we suspect they may have guided the selection.

TEACHER: Andy, say something beginning with ‘I’.

ANDY: I is…

TEACHER: No, Andy, you must say ‘I am’.

ANDY: I am the ninth letter of the alphabet.

Contents

Finding out about the awful contingency of humour is a very deflating childhood experience. Babies and toddlers are extraordinarily funny, so by the time you come to self-consciousness around the age of five or six you’re used to provoking indulgent adult laughter without any effort at all. And then, just as you’re beginning to associate comedy with love, popularity, and getting away with murder, it suddenly becomes much harder to pull it off.

Asking Auntie Mary why she has decided to grow a beard stops being funny and instead gets you a smack. Friends who used to giggle when you repeated the same phrase over and over now say it’s boring and stupid. Your dad will howl at a joke on TV, but when you tell him the very same joke a couple of hours later he won’t laugh at all. Inexplicable. Meanwhile there’s at least one child in your year accumulating friends by the bucketload because of an ungovernable comic flair that cannot be learned in books.

Wait, though! What’s this in the paper bag stamped with the logo of your local independent bookshop (there was no Waterstones in 1978)? Maybe being funny can be learned in books after all. Because while The Crack-a-Joke Book contained an awful lot of filler (the allusion to cracker jokes is not accidental), there was a decent proportion of killer: jokes that gloriously, genuinely made people laugh, even when being haltingly read aloud by a seven year old.

It didn’t actually make you funny. Being funny requires subtlety, spontaneity, timing, empathy - a whole host of stuff at which small children do not traditionally excel. But it did give you some solid jokes that you could learn by heart and pull out of the bag at will. The more you read and ingested it, the more fluent you became. This book allowed an entire generation to stop worrying about their material and really focus on their delivery.

FIRST CLEVER DICK: Every day my dog and I go for a tramp in the woods.

SECOND CLEVER DICK: Does the dog enjoy it?

FIRST CLEVER DICK: Yes, but the tramp’s getting a bit fed up.

Afterword

The young Generation X in the UK benefitted hugely from its curators, the benign experts and enthusiasts who gently sifted the culture and pushed the best stuff our way. Kaye Webb was a colossus of curation, and together with BBC children’s TV supremo Biddy Baxter she steered the cultural consumption and taste of millions of children. On taking over Puffin Books in 1961 Webb executed a strategic masterstroke, buying the paperback rights to almost every significant children’s book from the previous half-century or so: Watership Down, the Narnia series, the Bagthorpe saga, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory… just look at the list. This omnivorous selection, in affordable editions with parentally-trusted branding, put hundreds of stone-cold classics into the mass market. By the time The Crack-a-Joke Book was published in 1978 Webb had increased the number of Puffins published annually from 12 to 128.

There was a class aspect to all of this, and to illustrate it we invite any readers who were Puffin Club members to tell us in the comments whether they were allowed to watch ITV. (Three of the four Metropolitan editors were not; two because of its unspeakable commercial vulgarity, and one because her dad worked for the BBC and resented the competition.) But the wide availability of classic children’s literature, together with a deliberate emphasis on new work by authors from a variety of backgrounds, reverberated via schools and libraries across the land.

The Crack-a-Joke Book doesn’t stand up particularly well. Few of the jokes are actively offensive, but some of them wouldn’t make it into an equivalent collection now. Actually, hardly any of them would make it into an equivalent collection now. As a comparison in the effectiveness of crowdsourced humour, try putting The Crack-a-Joke Book up against TikTok. The average freely-available joke in 2022, drawing on the comic inventiveness of millions, is just better. We might, if we are very quiet and good, live to see the extinction of the lazy pun and the tortured near-homonym, twin spectres that haunt this volume like a bad smell (‘Why wouldn’t the man eat an apple? His grandmother died of apple-plexy.’) But if you were a child in 1978, suddenly able to direct the power of laughter like a tiny magus in cord dungarees, it was pure exhilaration.

At around the same time, although we weren’t yet old enough to know it, comedy was flexing and reshaping, undergoing one of its periodic generational shifts. Not The Nine O’Clock News was first broadcast the next year, The Comic Strip Presents the year after that; Alternative Comedy was getting on with the job of despatching Jim Davidson. Out with blatant racism, whoops-there-go-my-trousers farce and mother-in-law jokes; in with absurdist Alexei Sayle routines and talking rats addressing the fourth wall in The Young Ones. Many of our generation’s best and most totemic comedies - The Day Today, Hot Fuzz, The Office, Eddie Izzard’s stand-up - combine a hallucinatory silliness with a pinpoint subversion of form. Our comedies bent towards presentation and away from material commentary, and now our generation’s most significant British politician is Boris Johnson, the embodiment of Peter Cook’s vision of Britain ‘sinking giggling into the sea’. Perhaps, in retrospect, they shouldn’t have encouraged us.

WAITER: How did you find your steak?

DINER: Quite by accident. I moved a few peas and there it was.

We’d love to hear your thoughts on this piece, the Crack-a-Joke book or just your favourite shaggy dog story (it’s the one with the penguin in the park, isn’t it?).

Let us know what you think

For more on the curators who shaped the world for Generation X:

I was a Puffin Club member… and while I wasn’t banned from watching ITV, I do very much remember that the view in our house was definitely that all the good stuff to be watched was on BBC! ITV was not really “our thing”… and I can recall going to my aunt & uncle’s house in Clapham where, every Sunday, the Golden Shot would be on, followed by On The Buses, which contrasted to Sunday viewing in our house of The Forsyte Saga! I know which I would have preferred at the time…

Thanks for the relevant memories! Why were Kaye Webb and Biddy Baxter never in the House of Lords? OK, that was a rhetorical question, but still... As for the TV comedy shift, the old stuff wasn't all Jim Davidson, and some of the "alternative" stuff is a bit cringe-making now (I give you Ben Elton's homilies! Actually, they were a bit cringe-making then) .Eric Morecambe was my comedy god, and I loved the Carry Ons, which count as TV because that's how we saw them. I am unrepentant. 😀