The corporate theory of value

I seem to have accidentally retired at the grand age of 54 (thus becoming one of the 50--64-year-olds whose ‘economic inactivity’ forms part of the Treasury’s ongoing cluster headache). Not being a productive node is inconvenient in some respects — we haven’t had a foreign holiday in a while, let’s put it that way — but honestly, it’s mostly brilliant. When people talk about the ‘dignity of work’ or the pleasure of their careers, I never have the faintest idea what they’re talking about. I’d always rather be on leave, because:

I’m fundamentally very lazy;

I’m not one of those people who becomes anxious when I don’t have anything specific to do; and

at the most basic level, I have never come to terms with the fact that half of my time — the essential commodity that comprises my existence, my one brief shot at consciousness — must be measured out and sold to other people by the day. I know this makes me sound like an A Level student directly after a prodigious bong hit, but there it is.

Nevertheless, over the decades I’ve needed to live in houses and eat food, and so I’ve been working for money (with breaks to contribute to the literal survival of the human race) for 33 years. At times, I’ve even enjoyed it. The thing I really haven’t enjoyed is the rising tide of professional management bollocks. And I think this might be another transition — like the UGC internet and the rise of populism — that Gen X experienced in real time.

For instance: if you’re Gen X, you too will remember a corporate function that used to be called ‘personnel’. But at some point in the ‘80s, the term ‘human resources’ was imported from the States and adopted by wankers.

In a sentence that can only have been written by someone who works in human resources, Wikipedia asserts that the switch in terminology ‘resulted in developing more jobs and opportunities for people to show their skills which were directed to effectively applying employees toward the fulfillment of individual, group, and organizational goals’. Like so many missives from HR this prompts a reflexive ‘what the fuck?’, but if you read it enough times the message becomes clear: this was a change from the functional (hiring, firing, retiring and paying) to the exhortative. Stuffy old ‘personnel’ did boring things, like paying your wages to the right bank account and clearing up problems with your tax code. HR ensures that you sing the company song, and reminds you to smile while you’re doing it.

I distinctly remember reading the words ‘human resources’ for the first time not long after I started my very first proper job in 1992. I didn’t really think about any of the wider implications; I just noticed that it made me sound like a herd animal on the way to the abattoir. Relatedly, it was around this time that office workers were gathered together in vast sheds under bright lights: the ‘open plan office’, a panopticon with Garfield desk calendars. No opportunity to snort, stretch, yawn or cry in private; nowhere to have delicate conversations or tricky phone calls; no chance of staring out the window for 15 minutes before returning, refreshed, to your inbox. Your employer had bought your consciousness by the yard, and wanted to keep you under its revolving eye while extracting every last drop of compliance. (Not performance; compliance.) And anyway, you were several hundred yards away from the nearest window. The only thing you could see was the foam partition walls of what Douglas Copeland called the ‘cattle pens’.

That first job was a doozy all round. I shouldn’t have been offered it — it was a technical role, and I wasn’t remotely qualified — but the hiring manager was an older man who, I suspect, found me compelling for reasons unrelated to my competence. My line manager, a woman who (quite rightly) had wanted to hire literally anybody else, decided to make my working life as unfulfilling as possible in the hope that I would bugger off and allow her to re-open the recruitment process.

I didn’t need to be encouraged to get a different job; I’d worked out for myself that I’d made a terrible error. But there was a recession on, so it took me a three years to get a job offer: three years in which I attended compulsory parties in Weybridge hotels, received three chocolate penises in three successive Secret Santas (I ‘brought this on myself’ by angrily throwing the first one in the bin), and pretended to learn the principles of Total Quality Management (which was everywhere in the ‘90s). Three years in which I somehow survived three waves of redundancies mandated by management consultants, and watched as the North American parent corporation drove a 200-year-old British publishing house out of its wits and then to the brink of extinction. By the time I left, I had spent a lot of time wandering around the building, looking for walls to bang my head against.

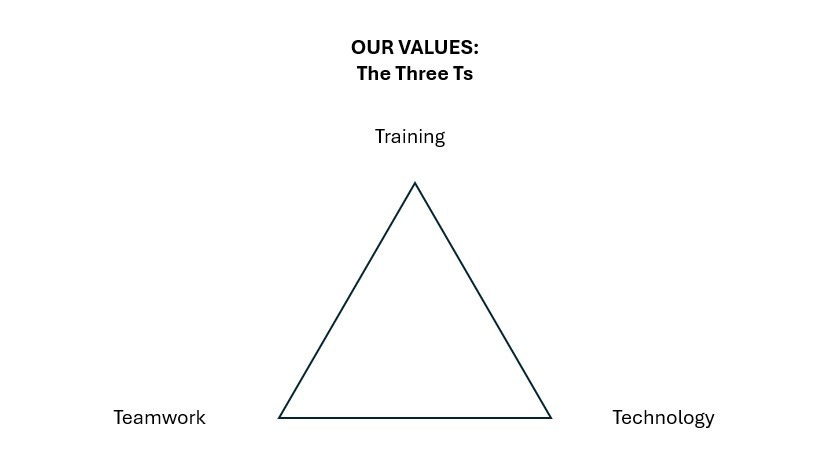

It was during one of these desk-dodging trips — I think I’d been on a cigarette break — that I saw an A2 poster that had just been hung in the stairwell. I reproduce it here, using exactly the same levels of care and thought that went into the original:

That really was it: just a giant triangle with three labels and acres of white space. Bearing in mind that this was a company that employed a team of graphic designers, the howling visual incompetence was a calculated insult all by itself.

It was quite impressive, really, that this poster contained so many grotesqueries in such an abbreviated form: the assertion that a corporation has ‘values’ (and, by implication, personhood); the revealed belief that employees are gaping moral voids in need of basic instruction; the conceptual mire (these things interrelate how? How is ‘technology’ a value? Why a triangle and not a circle?); the ickle-wickle Sunday School tone. But more than all of this, I objected to the bald-faced lying. This was a company that didn’t give me a day of training in three years of employment, and my only experience of ‘teamwork’ was that my manager wanted to hurt me.

That poster drove me absolutely bananas for the remainder of my time there. It wasn’t just that it made me want to shout ‘TIZER!’ or ‘TITS!’ or ‘TERRY THOMAS!’ every time I went past it. No: it was the infernal, contemptuous shithousery. And it’s driven me bananas ever since I left; it has lived rent-free in my head for decades, because it’s absolutely emblematic of the intellectual prostration that management bollocks requires of employees. Not only does management bollocks consist of things that are meaningless or patently untrue, but it also requires staff to pretend to believe them, to give presentations in which they say things like ‘And here’s how this activity lines up with our values!’

It’s this, I think, that has made me so mulish over the decades. I don’t like having to sell my existence by the yard, but I can cope with it. Employers have the right to require specified work to a specified standard, appropriate behaviour, and the presence of both of my bum cheeks in a designated chair; but I’ve never accepted that they have the right to direct my thought processes. I cannot bear having to pretend that I believe things that I don’t believe, especially when those things are directly contradicted by the evidence of my own eyes. I refuse, for instance, to acknowledge that ‘teamwork’ is a ‘value’, as opposed to an utterly basic requirement of functional working. Like ads for reformulated products, the real utility of ‘company values’ is that they are infallible tells. If a company cites ‘transparency’ as a value, you can bet your house that the culture is irredeemably furtive.

When I talked to my mother about all this, back at the tail end of the last century, she pointed out that I come from a long line of shop stewards. Of course, thanks to Mrs Thatcher, I’ve never worked for an organisation that recognised a union; and, thanks to the union movement, until a few years ago there wasn’t a union that represented workers in my field (corporate editorial and communications: the ‘effete bastard’ functions).

And anyway, what would a union have offered me? My work was not dangerous; I was not at risk of industrial injury; I didn’t work shifts; I wasn’t badly paid. (People in my sector get made redundant a lot, but so does everyone.) My complaint in that first job — the insidious, injurious, undignified, coercive requirement to recite corporate horseshit — was less material, and more difficult to address. My employment contract was, in effect, a non-compete clause on my cognition, a promise that I would not think on company time. They should have put that on the poster. At least it would have had the value of honesty.

I’m gonna need you to go ahead come in tomorrow. So if you could be here around 9 that would be great, oh! and I almost forgot, I’m also gonna need you to go ahead and come in on Sunday too, kay? We ahh lost some people this week and, we sorta need to play catch up.

One of the great things about being a lorry driver (apart, obviously, from getting to play with ginormous toys all day) is that the haulage industry, by and large, is entirely free from this sort of silly bullshit. I do recall seeing a poster exhorting me to identify myself as "Team Scania" and compete against drivers from "Team Volvo" or "Team DAF", but thankfully this sort of thing was rare and treated with the contempt it deserved by the drivers.

Great article. Reminding me about TQM which I always thought as telling me what I couldn’t offer! My favourite management course concept was the ‘cone of destiny’ (a poster with a cone on it, marked destiny’) which I rolled up and put on my head to no one’s amusement