The Wire (2002—08)

We have been re-watching The Wire this month, for no better reason than one of the bona fide young people in the house started a re-watch over the summer holidays and we immediately decided to copy him.

One of the things that stuck out this time around was how traditional it is. The first season, for example, is really just a ‘getting the team together’ show, like any number of police procedurals, thrillers, superhero flicks, and movies about everything from a capella girl groups to the Second World War. (The second season, therefore, is a ‘getting the team back together’ show.) A group of misfits are pulled together and gradually discover how their individual talents can mesh together into a team. (Except for McNulty.) It’s basically The Seven Samurai in a Baltimore basement.

You mostly don’t spot this clichéd approach on first watch because of the general excellence. It’s also obscured by the writers’ decision to run it in parallel with another cliché: Shakespeare’s history plays, but make them gangster. That too has been done a thousand times, but when woven in with the McBain procedural and Kafka-esque bureaucracy of the police story, it becomes something new.

The medium wins out in the end, though. Season One is extraordinary, Season Two has its charms, and Season Three is a soupy, soapy mess. This is the season where the show starts huffing its own fumes and tries to become an inquiry into contemporary American institutions, which mostly means characters keep stopping to deliver pompous monologues about the THEMES while having vigorous affairs featuring HBO levels of nudity. (Our resident second-wave feminist remains deeply unimpressed by the unreflective, glassy-eyed directorial gaze used in the strip club scenes.)

Still, we still have the last stretch — Season Four — to go, and we’re looking forward to that because it’s the achingly sad one about education. (Thank goodness they didn’t go on to make a self-indulgent and largely unbearable final season about the media.)

Damascus Station (2021), Moscow X (2023) and The Seventh Floor (2024), all by David McCloskey

Another bit of self-indulgent summer nonsense: I’ve been re-reading this trilogy of spy novels by David McCloskey, an ex-CIA analyst and now co-host of the podcast The Rest is Classified. If this is the kind of thing you like, I thoroughly recommend them. This time around I found them even more compulsive than I did the first time around, and I thought they were pretty good then.

Like any good spy thrillers, they require you to do a little bit of cognitive work, but not too much. They also feature a satisfying amount of real-world political commentary and information, which is probably why this genre tends to be popular with journalists and politicians. I finished Damascus Station feeling that I had learned something about how the Syrian professional classes interacted with and coped with the Assad regime, which was not a perspective I’d considered before. The descriptions of life in Damascus — a place that, let’s face it, I am absolutely never going to visit, because I prefer to remain alive — were vivid without feeling patronising.

McCloskey is one of any number of spy thriller writers who have had the misfortune to be called ‘the new le Carré’. The thoroughly enjoyable Seventh Floor is even a flat-out homage to Tinker Tailor; but what I like about McCloskey is that he clearly knows any serious comparison is ridiculous, a knowledge that he communicates through the medium of scatological humour.

I have wasted so much money on dreadful spy novels whose promotional blurb featured the words ‘the new le Carré’ or ‘deserves le Carré’s crown’ that any sight of this claim makes me instantly suspicious. It’s nothing more than dreary, dishonest hyperbole. Presumably it helps to sell books (although it doesn’t stop readers feeling hoodwinked and resentful afterwards), so I suppose it’s hopeless to ask publishers to stop putting this bollocks on the cover. But if you are a book reviewer about to write that a perfectly workaday spy novelist is ‘the new le Carré’, I really wish you would stop to consider whether what you really mean is that:

they write sentences that include subjects, verbs and objects in an unobjectionable order;

their narrative implies that Western governments are fallible; that some civil servants, politicians and spies are bad people; and that the practice of espionage and counter-espionage twists the old brain-box a bit; and

their fictional spies are commitment-avoidant and have substance dependency issues.

Because, you know, those things are not why le Carré was good.

Like Hilary Mantel, he was a one-off. Both took a genre form — in le Carré’s case, a genre form he’d been plodding away at unremarkably for quite some time — and suffused it with wisdom and humanity until it splintered into genius. I’m not saying we’ll never get another spy novel as good as Tinker Tailor or another historical fiction novel as good as Wolf Hall. I’m just saying that if we do, we’ll bloody well know them when we see them. We won’t need to be told.

In the meantime, though, McCloskey is much, much better than the average.

Letterboxd Diary

Jaws (1975)

Fifty years on and I still can’t swim. Anyway, it's the anniversary and I was watching the John Williams documentary where he describes playing the theme to Stephen Spielberg for the first time and I realised I hadn’t seen it in a while.

The second half is what you remember. I preferred the first half this time round, although it's perhaps something of a Metropolitan cliché that I was more interested in the battles of small town bureaucracy than the bro-off on the briny deep. The town meeting that Quint interrupts is a fantastic little scene, like something out of Kurosawa’s High and Low (1963) or Ikiru (1952): every frame packed with faces. And what faces. Gold star for the casting director.

Good Morning (1959)

A great little Yasujirō Ozu movie about the changing mores of post-war Japan. The main point is in the comparison between the fatuity of the adults — all those ‘good mornings’ — and the flatulence of their children, whose greeting ritual involves farting on command. One of them always follows through, ruining his trousers, which Ozu seems to be comparing to the vicious gossip that underlies the outward politeness of their mothers.

The film appears to be saying that in ‘50s Japan — where no one has a job, and all children need English lessons to prepare for the new world — the old etiquette has no place. The children mount a strike to make their parents buy them a TV, a tactic that succeeds. On the other hand, the surface politeness does at least ensure that the gossip never erupts into outright antagonism, and everything can be smoothed over in the end. The English teacher gets the girl because of his good manners. Those meaningless pleasantries have a meaning after all.

In its depiction of post-war Japan it’s a great companion piece to those Kurosawa movies I mentioned earlier, and in beautiful colour, too.

Possibly the best recommendation is that Ro’s Dad wandered in as I was watching it and despite it being halfway through, in subtitled Japanese, and containing a good deal of amusingly dubbed farting, he stopped and watched, rapt, for the rest of the movie. At the end he said: ‘I couldn’t tell you why, but that was very watchable.’ Hard agree.

Barry Lyndon (1975)

I had the absolute pleasure of going to the big screen at the BFI with friend of The Metropolitan Adam Frost to see what I think is my favourite Kubrick film. What astonishing work of art it is. Trying to think of something to say about it is rather like being the proverbial blind man describing an elephant. It feels simply too big to approach in any meaningful way.

It did make me think about how images of the eighteenth century permeated my ‘70s childhood. Toile patterns and Doulton figurines, rainy afternoons spent traipsing past the Gainsboroughs in National Trust Houses, the covers of Georgette Heyer novels, holidays in Lorna Doone country and smuggler’s Cornwall.

The eighteenth century is, after all, the period in which the legend of a kind of Britishness is being constructed: John Bull and the chinless wonders, the ragged red square and the ruling of waves, the country vicar and the weary ploughman, the mutinous mob and the chiming of tea china in pale green sitting rooms. The rococo and neo-classical houses of the aristocracy, nabobs and nobles both, the rococo and neo-classical rules of etiquette, class structures and attitudes. All apparently studied and stultified, restrained and refined, and yet all paid for and powered by the nascent Empire, by violence and scandal, riot and rapine.

Although, unlike the later seasons of The Wire, Kubrick restrains from hitting us over the head with them, these themes are right there in the film: a film made after the fall of Empire, adapted from a book written at the Victorian height, set in its eighteenth century opening chapters. But so are those images: a grand house in the mist, a garden full of passing figures, a dog in a boat on a lake, card players and soldiers and lonely individuals in great rooms. Every frame an etching, every composition perfectly framed and lit but all splendidly, compulsively alive.

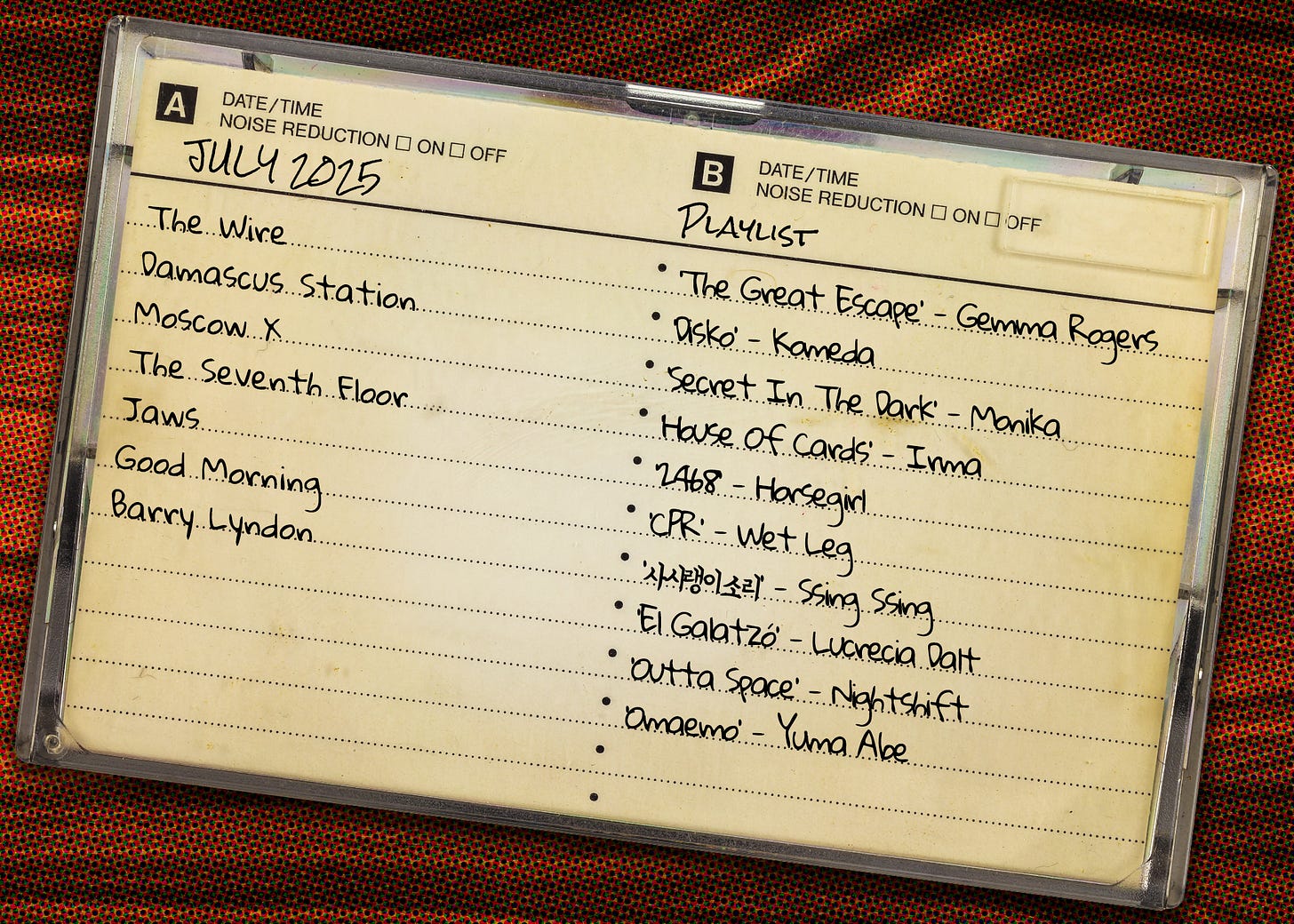

Tracklisting

Ten tracks I’ve had on repeat this month. The playlists are all on Spotify.

The Great Escape - Gemma Rogers. Oh yeah, summer is supposed to be holiday time, isn’t it. The Metropolitan isn’t going anywhere though (paid subscriptions are available, hint hint), but maybe we can travel through the magic of music.

Disko - Komeda. Sweden first. For some reason Spotify chose to remind me of the excellent Komeda this week, so here’s my favourite track of theirs.

Secret In The Dark - Monika. Greece with Monika Christodoulou, who, judging from her Tiny Desk Concert, is quite fearsomely, Hellenically extra.

House Of Cards - Irma. Of course Paris in Summer is empty. And also smelly. But still Paris, after all.

2468 - Horsegirl. I’ve only ever been to Chicago to change Greyhound buses. Maybe I ought to visit properly.

CPR - Wet Leg. But then does Chicago have an outsider theme park like Black Gang Chine? What could be a more appropriate British holiday than the Isle of Wight in the rain?

사시랭이소리 - Ssing Ssing. Mind you, all the kids want to go to South Korea, of course.

El Galatzó - Lucrecia Dalt. It's only 14° in Bogotá as I type this, which sounds extremely appealing.

Outta Space - Nightshift. Even Glasgow is hotter than Bogotá right now. Scotland isn’t supposed to be warm. It’s not right.

Omaemo - Yuma Abe. Japan is apparently experiencing something of a tourist overload at the moment, though, so perhaps it's best that we just stay home and listen to the music instead.

The whole playlist is on Spotify here:

In case you missed it, this month we published our first essay in our new season, Sherlock Holmes on film:

Thanks for recommending Good Morning - I’m so intrigued by the farting that I’ll have to check it out

I would argue, mind you, that Len Deighton is at least the equal of le Carré, and perhaps more innovative.