Metropolitan Mixtape: September 2025

The American Civil War, The Russian Revolution and Jimmy Kimmel

The only funny thing Jimmy Kimmel ever did

Despite the fact that Everyone Is Talking About Jimmy Kimmel All Of The Time, I haven’t seen anyone mention this clip from 2007. I thought this might be another case of the memory-holing of core Gen X content, but when I talked to Tobias about it he had no idea what I was referring to, so maybe I’m the only person who ever saw it? It’s too good to keep to myself, so here you go. (NB: not safe for work/children.)

https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x48p7b

The American Civil War

Question: where (if anywhere) have you heard this song before?

If you’re shouting ‘Ken Burns!’ then congratulations: ‘Ashokan Farewell’ (written by Jay Ungar, the guy on lead fiddle in the above clip) is the unforgettable theme tune to the 1990 PBS series ‘The American Civil War’, which propelled Burns to as much stardom as is possible for a man who makes documentaries.

We’ve been marinating in US Civil War content this month, prompted initially by The Rest is History’s series about the assassination of Abraham Lincoln (7/10, assuming you like the Holland/Sandbrook senior-common-room schtick, which I do). This turned out to be a mild plug for the Apple TV series Mahhunt, which is about the aftermath of the assassination and the hunt for John Wilkes Booth, history’s most evil thespian, which is really saying something. Manhunt is quite silly; it goes large on a slightly crazed conspiracy angle. But it’s a useful introduction to the cast of characters who made up Lincoln’s immediate political circle, particularly his Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, who turns detective after his boss’s murder. (This seemed implausible to us, but is exactly what happened in real life.) Stanton is played by Tobias Menzies with his customary straight bat and clamped jaw, and Wilkes Booth is well done by the ubiquitous Anthony Boyle. Rating: 6/10 (would have been 7 without the confusing conspiracy stuff).

After this mild silliness, we turned to the masters. First up was Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln (2012), which focuses on the weeks before Lincoln’s assassination, as the war ends and Congress passes the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery. Lincoln is basically a two-and-a-half-hour episode of The West Wing, in the best possible sense: densely plotted, literate, funny and tight. Many of the actors are spookily accurate physical doubles for their real-life counterparts, particularly Daniel Day-Lewis as Honest Abe, David Strathairn as Lincoln’s Secretary of State William Seward, and Jared Harris as Ulysses S. Grant. (Harris is apparently keen to star in an adaptation of Ron Chernow’s recent biography of Grant, which would be amazing.) There’s also a capering cameo by a delightfully gone-to-seed James Spader. 8/10, assuming you like The West Wing.

Next was Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals (2006), the book that inspired both Spielberg’s film (Kearns Goodwin co-wrote the script) and Barack Obama when he was thinking about running for president. Team of Rivals – whose other famous fans include Sir Alex Ferguson – is an absolute banger, full of snappy character sketches and clear explanations of what the hell was going on. It also offers a pleasingly minimal treatment of the actual battles. 8/10 unless you like military history, in which case you will be disappointed.

(As a chaser, you could try Gore Vidal’s novel Lincoln (1984), which tells almost exactly the same story but in a thinly fictionalised form. After a lifetime of listening to Boomers wittering on about Vidal, this is the first book of his I have read, and on this basis I can’t quite see what the fuss is about; it’s a competent and enjoyable 7/10, but he ain’t no Hilary Mantel.)

And then there is Burns’s The American Civil War (1990, PBS, available on Now TV in the UK). It’s hard to describe now how much this shook up the documentary form when it was released: I remember my dad, who made historical documentaries for the BBC, watching it with wordless intensity when it was first broadcast. Burns’s slow panning across photographs was so visually successful that he gave his name to an iMovie effect, and his use of famous actors to read soldiers’ letters and politicians’ speeches kicks the whole thing up a level. Morgan Freeman, most notably, is unforgettable as Frederick Douglass, and Sam Waterston brings great comic timing to Lincoln’s many quips (my favourite of which concerned a superstar general who repeatedly refused to engage the enemy: ‘If General McClellan is not going to use the army, I would like to borrow it for a while.’) I have a theory, though, that it’s the music that really makes it, invoking a depth of emotional response not typically associated with documentaries. How can you hear ‘Ashokan Farewell’ or the a capella version of ‘Jacob’s Ladder’ and not be thoroughly hooked?

As with most of the films, programmes and books mentioned here (Manhunt, made after the Black Lives Matter movement, is an exception) The American Civil War is neither forensic nor thorough in its coverage of slavery and racism. Spielberg took heat for leaving Frederick Douglass out of Lincoln; Burns has been criticised for giving too much airtime to the writer Shelby Foote, whose position on the Confederacy is queasy at best. (Weird fact: Daniel Craig supposedly studied footage of Shelby Foote to develop Benoit Blanc’s accent for the Knives Out movies.)

The delighted smile that appears on Foote’s face every time he mentions Nathan Bedford Forrest – slave trader, Confederate general, and first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan – is revolting. But then, this was filmed at a time when outright memorials to Bedford Forrest littered the southern states. As a Brit it’s tempting to think we would never tolerate such an active celebration of enslavers and racists, but then you remember the bust of Cecil Rhodes that still clings to the facade of Oriel College in Oxford. We’re really in no position to judge. Its political analysis is – as they say – of its time; but for its sheer power and artfulness, and its long-term impact on the form, you have to give The American Civil War a solid 9/10.

Letterboxd Diary

What Tobias Sturt has enjoyed watching this month.

I Live In Fear (1955)

My regular dose of Kurosawa. This is a fascinating film of post-War, Cold War Japan, about an elderly business man (Toshiro Mifune) who is so terrified of nuclear war that he is trying to sell everything he owns in order to move to Brazil, where he thinks he and his family will be safe. His family, however, don’t want to go, his workers don’t want him to close his foundry and the courts eventually find him insane. But as the doctor in the asylum points out, is it not insane to continue to act as if it’s normal to live in a world in perpetual threat of being destroyed? But then what can you do about it? Is it not also insane to rail uselessly against fate?

What’s fascinating to me is that the film seems to be trying to present the conundrum rather than take a definite position. Nakajima, the businessman, is perfectly justified in his terror, but increasingly hysterical and unreasonable in his actions. His family are selfish and stubborn but also entirely justified in resisting his bullying, just as he is trying to resist the horrors of the world.

The film opens with footage of busy streets. Are all these people insane for continuing to live with their fear? This is Japan, after all, the only country to be attacked with nuclear bombs during a war. But they were only attacked because of the cultural insanity fostered in the country by those in power, men like Nakajima himself. The only possible conclusion seems to be the one we all lived with even into the ‘80s: to continue to be insane and to live with the fear, because the alternative was a worse madness of despair.

It also features Mifune, who was in his mid-thirties, in a lot of old age makeup. There’s a story that George Lucas originally wanted him for the part of Obi Wan Kenobi in Star Wars (1977). Star Wars was heavily influenced by Kurosawa’s own Hidden Fortress (1958), in which Mifune stars as an undercover general helping an escaping princess with the help of two comedy servants. I was reminded of all of this because Mifune’s performance put me in mind of Alec Guinness who, of course, played Kenobi. Although their affect is different, the two actors are similar in that they have two modes: acting, or ACTING. With Mifune you’re either going to get the wild energy of I Live In Fear and Rashomon (1950), or the magnetic, contained force of Yojimbo (1962) and High And Low (1963). Likewise with Guinness, it’s either the funny hats and brilliant caricatures of Kind Hearts And Coronets (1949) and The Ladykillers (1955), or the extraordinary subtlety and power of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (1979).

Much as I would have liked to see Toshiro Mifune as a Jedi knight, I think I would have liked even more to see Guinness play Kenobi as a member of the D’Ascoyne family.

Doctor Zhivago (1965)

That last thought was partly prompted by finally watching this, which features Guinness in ‘fright wig and false teeth’ mode. He pulls it off expertly, as ever. Pretty much everyone is pretty good in Doctor Zhivago, although no one’s properly excellent, apart from maybe Geraldine Chaplin. I wasn’t entirely persuaded by Omar Sharif; but Zhivago himself is such a monumentally self-absorbed twerp that he barely notices the Russian Revolution, so perhaps Sharif’s dreamy vacuity was perfect.

The film itself — yet another ‘classic’ that I had avoided largely because it was ‘classic’ — turns out to be brilliant. It could have been a turgid, cast-of-thousands, walnut-veneered epic; but Robert Bolt’s script is great, Freddie Young’s photography is beautiful, and David Lean is, after all, one of the greats, and possibly the absolute best at this kind of thing.

A lot of the visual storytelling is somewhat on the nose — such as the petals falling from a sunflower as Lara leaves Zhivago in the hospital - but on such a canvas, it works. It also means we don’t have to endure any actual poetry, thank goodness. Bolt and Lean evidently decided that we’d more readily believe that Zhivago was a poetic genius if we didn’t have to hear any of his verse, which was very sensible of them. Instead, wolves howl; Lean pushes in on the delicate frost on a window; we see the low, crimson sun through the birches; Jarre whangs up the balalaikas in the mix; and lo! Deathless words have been plonked down on the page, and we can fade to the next scene without having to listen to any of them.

Anyway, after years of knowing nothing of it other than ‘Lara’s Theme’, I finally see what all the fuss was about.

Man With A Movie Camera (1929)

Speaking of the Revolution, here’s an extraordinary slice of life in Russia a mere decade later. Dziga Vertov takes a movie camera to the streets of Moscow, Kiev and Odessa and films everyday life there. It’s amazing to see these scenes from a century ago, but even more amazing is the editing and effects; through them Vertov creates an thrilling poem of motion, a celebration of cities, movement and cinema.

Its speed and inspired glee feel extraordinarily modern, as does the way he includes the camera in his footage, building a sense of a world now endlessly observed, in which life will never again be fully separated from performance, and in which film will become the all-purpose cultural metaphor.

Also, the version on the BFI Player has a fantastic score from Michael Nyman, which matches the hectic collage of industry and invention.

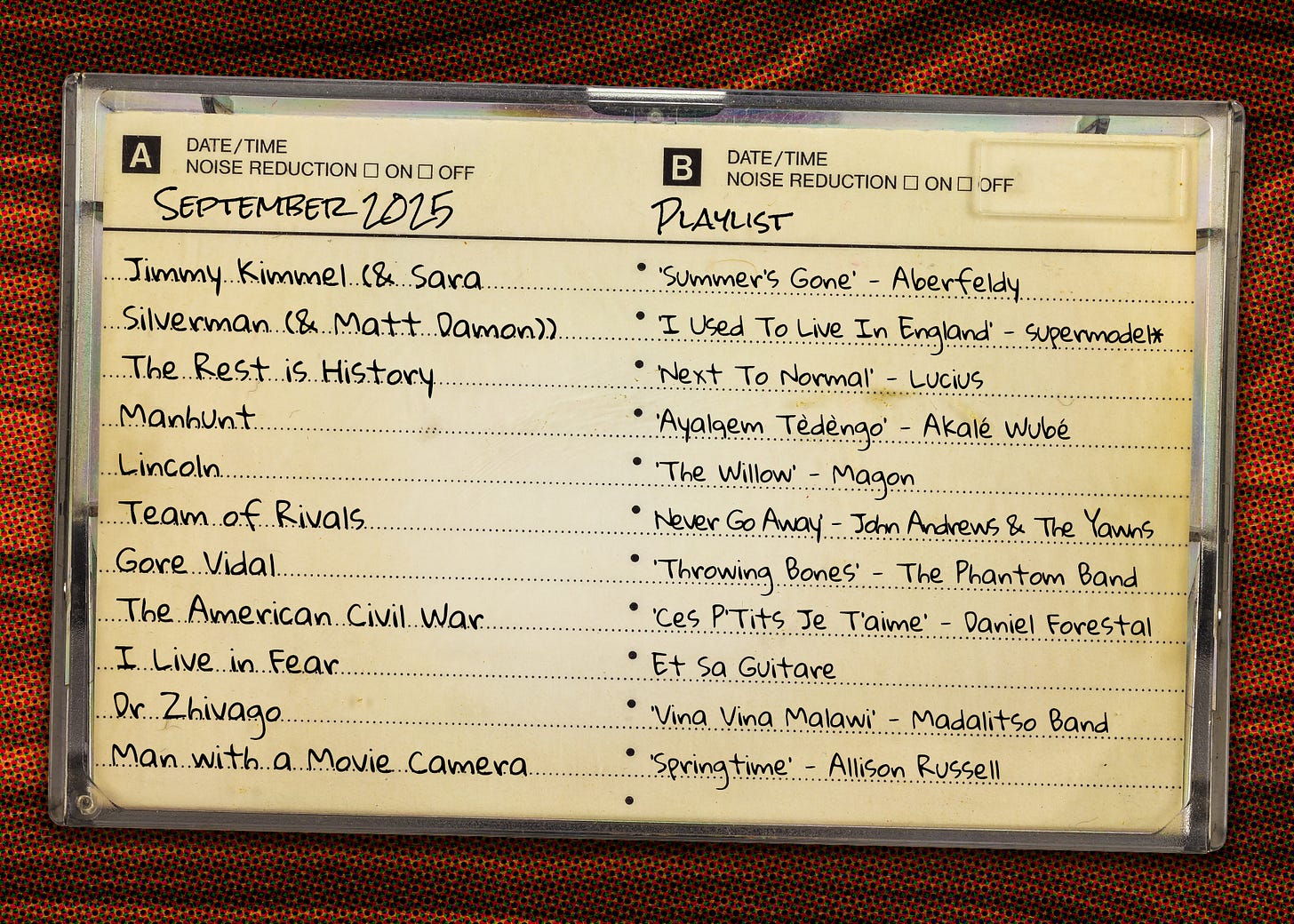

Playlist

What Tobias has enjoyed listening to this month. The playlists are all on Spotify.

‘Summer’s Gone’ - Aberfeldy. I know this is going to upset some of you, but summer really is over now.

‘I Used To Live In England’ - supermodel*. Having lived in England, this gentleman would know that autumn is absolutely the best season for it.

‘Next To Normal’ - Lucius. However, here’s some upbeat disco-adjacent groove for everyone mourning the shortening days.

‘Ayalqem Tèdèngo’ - Akalé Wubé. Followed by a cheery Ethiopian inflected instrumental. There’s sun somewhere, if you can find it.

‘The Willow’ - Magon. Here, though, the shadows are deepening under the trees and the evenings are getting chillier.

‘Never Go Away’ - John Andrews & The Yawns. Although autumn can be cosy if you really embrace it.

‘Throwing Bones’ - The Phantom Band. The Scots know how to deal with long, dark nights: stay inside and raise a ruckus.

‘Ces P’Tits Je T’aime’ - Daniel Forestal Et Sa Guitare. As far as I can tell, Daniel Forestal was from Guadeloupe, so perhaps this offers an escape to everyone who’s sorry to see summer go.

‘Vina Vina Malawi’ - Madalitso Band. Or Malawi? It certainly sounds cheerful.

‘Springtime’ - Allison Russell. But then, if autumn’s here, it means spring is coming. Eventually.

The whole playlist is one Spotify:

Our current season for paying subscribers is a study in screen Sherlocks and, this month, in screen Sigmund Freuds too:

“I used to live in England”. Tune. Best track LCD Soundsystem never made.

Acknowledging the criticisms, I still think The Civil War may be the best documentary television ever made, for its sweep, its texture and richness, its ambition, its humanity and its influence. A staggering achievement. I go back to it frequently like a hot bath, to soak. And Jay Ungar is superb.