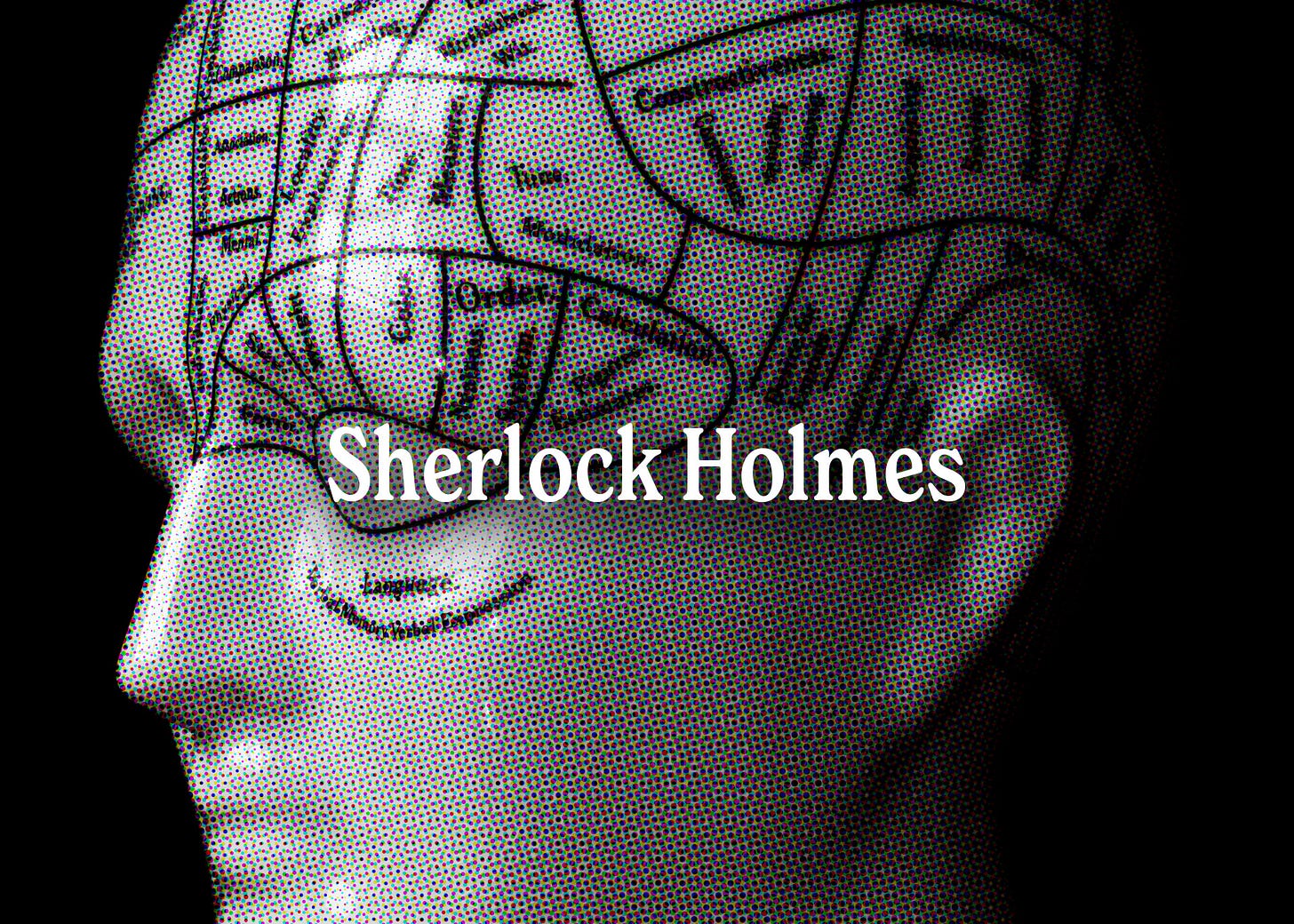

We continue our season of Sherlock Holmes adaptations by getting all meta about it and watching three faintly satirical, faintly revisionist films from the ‘70s which deliberately fudge the difference between fact and fiction by pretending Sherlock Holmes was a real person and using him to create alternate histories of the nineteenth century.

Last month I mentioned Powell and Pressburger’s The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), set during the Boer War, in the protagonist Clive Wynne-Candy has a spirited chat with a senior officer about The Hound of the Baskervilles. What I carefully omitted from that reference is that that officer has never heard of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

CLIVE

The author chap, sir - writes the Sherlock Holmes stories in the Strand Magazine.

THE COLONEL AT LAST SHOWS SOME ANIMATION AND INTEREST.

BETTERIDGE

This Doyle fellow writes the Sherlock Holmes stories?

CLIVE

Yes, sir. Conan Doyle. You must have seen his name.

BETTERIDGE

Never heard of him. But I've read every Sherlock Holmes story since they started in July '91.

Colonel Betteridge was not alone in not being fully aware of Sherlock Holmes having a creator. Right from the beginning, Sherlock Holmes has existed in a liminal state between fiction and fact. People wore black armbands when ‘he’ ‘died’ in ‘The Final Problem’ (1893). The Abbey National, which occupied 221b Baker Street from the 1930s onwards, was the recipient of letters begging for his help. In one 2008 UK poll, 58% of respondents said they thought Sherlock Holmes was a real historical person.

Three films of the 1970s capitalise on this, lifting Holmes out of his stories and splicing him into the real late nineteenth century. The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970) throws the great detective into a cold war with the Kaiser. Murder by Decree (1979) pits him against that most iconic of Victorian villains, Jack the Ripper. And The Seven Per Cent Solution (1976) puts its pitch plainly on the poster: ‘Sherlock Holmes meets Sigmund Freud’.

It is customary for apologists for the British Empire to insist that it did at least confer upon its colonies the benefits of nineteenth century modernity: bureaucracy, law, railways. (Admittedly, the laws were used to constrain the colonised; the railways allowed the movement of troops; and the bureaucrats arranged for the latter to enforce the former.) And those three words also summarise a model Holmes story: ‘Hand me my case files, Watson’; ‘To Paddington, cabbie, and there’s a guinea in it if we make the Express’; “All yours, Inspector Lestrade.’ Files, trains and justice.

After the Second World War, as a wind of change blew away the former colonies and Britain’s own economy curdled and international standing dwindled, the imperial legacy was questioned. All of these films use a ‘real world’ setting to give the viewer a glimpse of the ‘real’ world of Holmes and Watson: the stories that Watson had supposedly left unwritten, the ‘truth’ behind the tales published in Strand magazine. But they also use Holmes as an emblematic Victorian -- the great brain of London -- to examine and criticise the Empire.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Metropolitan to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.