Letterboxd Diary

Tobias Sturt : My traditional self-indulgent Halloween horror movie watching has been much curtailed this year by illness (mine and others’), travel (for work) and the fact that I’ve watched all the classic Universal Monster movies now and I’m not sure I can face Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948).

I have managed at least to squeeze in a viewing of Lost Hearts (1973), technically a ‘Ghost Story for Christmas’, but a story which takes place over Halloween, so I think its allowed. However, we’ll almost certainly cover M. R. James and the BBC’s ‘A Ghost Story for Christmas’ strand at some point, so we’ll save that for the moment

Meanwhile, here’s some films I did manage to watch (alongside all the Sherlock Holmes content I’ve been forcing my way through):

The White Reindeer (1952)

We’ve had The Wicker Man this month, so how about some Finnish folk horror? A tale of love magic gone awry among Sami reindeer herders in Lapland. A neat little bridge from Halloween to Christmas, symbolically. This won Best Fairy Tale film at the 1953 Cannes Film Festival, from a jury led by Jean Cocteau, who knew whereof he spoke in that regard. It really is a strange and alluring thing, an immediately recognisable folk tale of broken hearts, curses and murder, but in a setting and cultural context that renders it new and extraordinary. All those snowfields lend themselves beautifully to black and white photography too.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962)

Our enquiry into the causes, course and consequences of the American Civil War has finally brought us — as it previously did American culture — to Westerns. (Also, Ro’s Dad is happy to watch them.) In the ‘40s and ‘50s there were war films; the ‘60s and ‘70s had called in the cops and spies as possible alternatives; and then Star Wars (1977) came along and changed everything. By the time Gen X was born, the Western hadn’t been the default action genre for some time. But my grandmother would watch anything with a horse in (especially if the horse had John Wayne on top), so I saw a lot of them as a kid.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is a classic: a John Ford movie starring both Wayne and Jimmy Stewart that, like most classic Westerns, is about the end of ‘the West’ and the myth of ‘the Western’. The story is that Jimmy Stewart’s Stoddard has become a US senator on the back of the popular belief that he faced down and shot a bandit, Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin). In fact, Liberty was shot by local gun man Tom Doniphon (John Wayne), who conceals his heroism so that Stoddard can win power.

As a child I completely missed the significance of Liberty’s name, and the film’s peculiarly American idea of the compromises of civilization: in order for civilization to flourish, liberty must die. A society that has laws, and protects its citizens from fear and want and oppression, is a society that has given up a purer kind of liberty: the liberty to be a bully or a bandit, or a fine, upstanding-yet-bowlegged varmint like Tom Doniphon. The film seems to sum up a core American dichotomy: a pride in technological democracy that co-exists with a yearning for the lost anarchic Eden of the unsettled West.

Perhaps it was no coincidence that Lee Marvin appears to have been the only Democrat on set.

Now Voyager (1942)

One of those classic films in which you finally discover where a bunch of tropes originate: the lighting of two cigarettes at once; brittle, allusive dialogue; the transformation of a thick-eyebrowed, frumpy maiden aunt into a glamour girl (Bette Davis). ‘Oh, Jerry, don’t let’s ask for the moon. We have the stars.’ Inevitably, it is utterly unhinged; a story of repressed and self-sacrificing passion from a repressed and self-sacrificing age. The age of heroic psychiatry, in fact; Claude Rains plays the twinkliest, most heroic of psychiatrists.

Something we noticed about so many of those great stars of the golden age — the stars, particularly, of so-called ‘women’s pictures’ — were not classical beauties, but rose and shone on pure talent and charisma: Davis, Joan Crawford, Katherine Hepburn.

Late Autumn (1960)

No Kurosawa this month; Ozu instead. Late Autumn is the story of a widow and her single daughter who are living happily together while all their friends try to separate them so that they can be married off. In this it shares key plot points with Ozu’s earlier (1949) black-and-white Late Spring, but Late Autumn revisits these plot points in a more modern Japan, and in colour. And what colour! Ozu insisted on shooting on German AGFA colour stock, a film that he referred to as ‘half-asleep’. Its colours, muted but luminous, are beautifully suited to the material: turn-of-the-decade Tokyo, the soft teals and primroses of ‘50s interiors, the jumble of neons and signage of the alleyways. Among its many other charms, it is an absolutely beautiful film.

The Candidate (1972)

Rowan has already expressed her opinion of this Robert Redford political satire, but I wanted to add that one of the many things that I (and I alone, apparently) enjoyed about it was that, as you would expect from a Robert Redford movie, the clothes were astonishingly beautiful, and worn with style, inevitably. Also, I would like to live in the Candidate’s house, thank you very much: all white-washed brick and hanging house plants, the interiors of the magazines of my childhood.

What Have I Done? by Ben Elton (2025)

Rowan Davies A hot take! I heard Ben Elton talking about his autobiography on a recent episode of ‘The Rest is Entertainment’, and had to download it immediately: I think this had something to do with the sheer velocity of his anecdotage (Rik Mayall, Adrian Edmonson, Dawn French, Hugh Laurie, Stephen Fry, Rowan Atkinson and John Lloyd were all mentioned within the first 180 seconds), combined with my own mild head cold. Definitely the kind of book you can gulp down in six hours while mainlining Strepsils.

I thoroughly recommend What Have I Done? if you’re of the age to remember the first transmissions of Blackadder, The Young Ones and Saturday Night Live. It’s a very satisfying (and non-ponderous) insider account of the meetings, the dreadful behaviour (Alexei Sayle comes off as a right wanker, as does Jonathan Ross), the lovely behaviour (absolutely everyone else), the parties, the script-writing and the studios; nerd heaven for anyone interested in the creative process. He talks a lot about the extraordinarily unpleasant ‘Oxbridge tutorial’ vibe in the Blackadder script table reads, and pretty much explicitly says this is the reason they will never make another one.

It also touches lightly on Elton’s personal story, without boring the reader rigid. I had never known that he was the nephew of the historian Sir Geoffrey Elton (the original Thomas Cromwell stan), or that he (Ben) suffered dreadfully from psoriasis throughout the years he was most prominently in the public eye.

Media coverage of the book so far has picked up on Elton’s very honest account of how much he was hurt by relentless criticism; not from the public (who happily consume whatever he is selling) but from actual, salaried critics and journalists, who have hunted Elton for sport throughout his career. I found his openness about this charming; relentless personally-inflected criticism must hurt a lot, and Elton has a puppyish eagerness to please that brings out the bully in a certain sort of writer. He considers briefly whether there might be some anti-Semitic animus here, although he doesn’t get too exercised about it. He concludes — and I think he’s right — that there’s a certain sort of cultural snob who cannot stand creatives who are both popular and successful. And Elton, for more than 40 years, has been both: sitcom writer, stand-up comedian, film writer, film director, librettist, musical director, novelist - he’s won awards for work in about ten separate fields. Must drive some people absolutely potty.

Most of all, the book reminded me of those mid-’80s evenings when I listened spellbound to Elton’s ‘little bit of politics’ monologues on Saturday Night Live. He’s not the best comedian of his generation, but those monologues were, I think, the very first time I heard a celebrity name and shame the absolutely endemic sexism of ordinary British culture. In the book he talks about being accused of ending Benny Hill’s career, because he had spoken on Wogan about how much he deplored Hill’s ‘comedic’ deployment of sexual harassment and voyeurism. As a 15-year-old girl whose relationship with her own body had been blighted by the mainstreaming of Hill’s predatory masturbatory fantasies, I remember wanting to stand up and applaud whenever Elton got onto the topic. No other famous ‘alternative’ comedian used their platform to highlight questions of women’s comfort and safety, with the always-excellent exception of Jo Brand. I really, really don’t ever want to see We Will Rock You, but I think Ben Elton is a bloody hero.

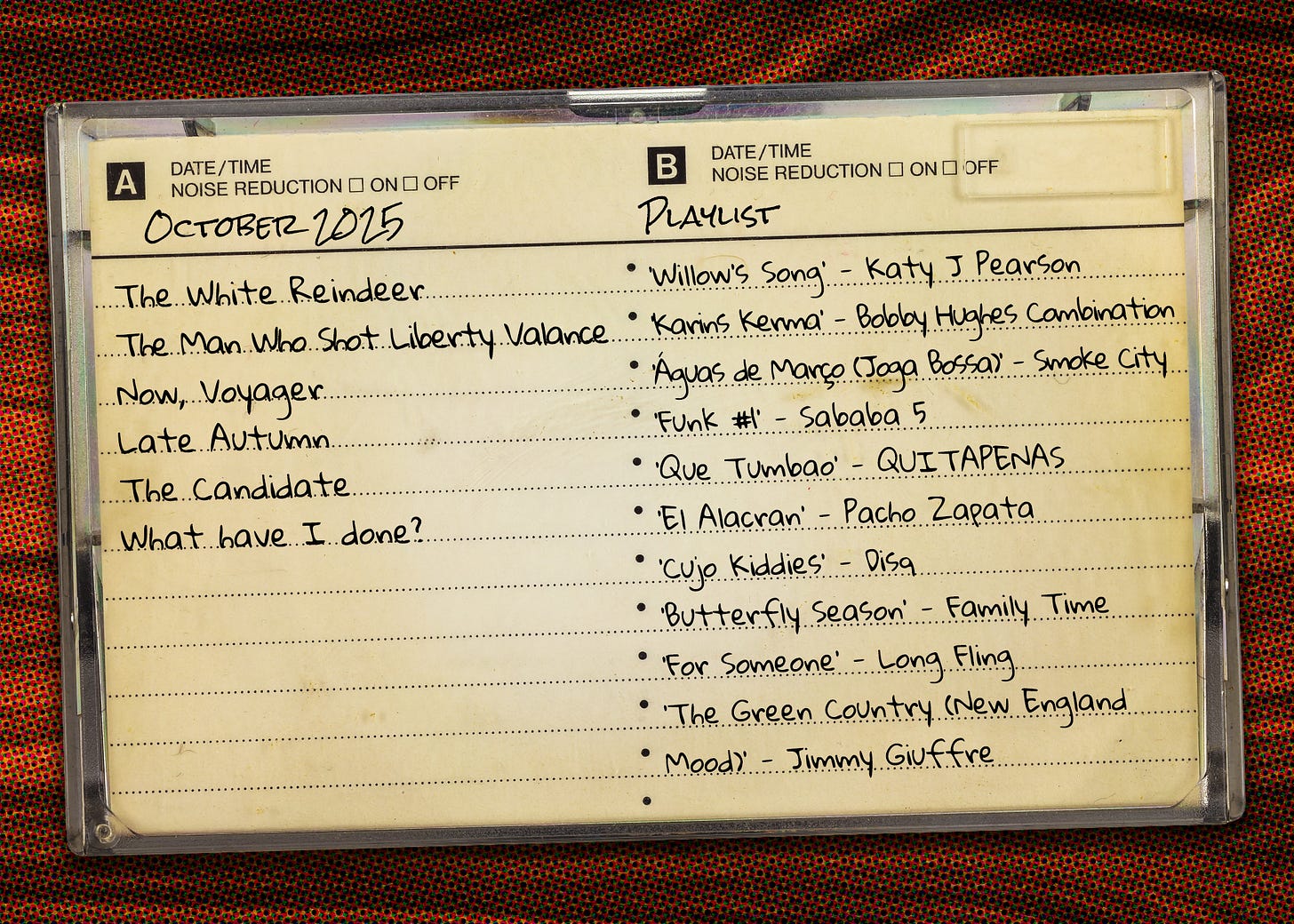

Playlist

What Tobias has enjoyed listening to this month. The playlists are all on Spotify.

‘Willow’s Song’ - Katy J Pearson. Proof, if proof be need be, that it’s not just middle-aged men who are fans of The Wicker Man. Although, to be fair, it is mostly middle-aged men.

‘Karins Kerma’ - Bobby Hughes Combination. Some splendidly smoky and slinky jazz from what turns out to be a Norwegian DJ.

‘Águas de Março (Joga Bossa)’ - Smoke City. I know we’re a long way from March right now, but this is one of my favourite songs and as a man of a certain age, I couldn’t resist a trip-hop cover of it.

‘Funk #1’ - Sababa 5. Some psychedelic Middle Eastern funk for you (which just a dash of hauntological synths to keep with this month’s folk horror theme).

‘Que Tumbao’ - QUITAPENAS. And now some psychedelic Latin American funk for a little change.

‘El Alacran’ - Pacho Zapata. Some fantastically unhinged organ.

‘Cujo Kiddies’ - Disq. ‘Cujo’ is an appropriately Halloween reference, right? (I have neither seen nor read it)

‘Butterfly Season’ - Family Time. There’s a love motorik style to this track, married to some lovely synth melodies. And the video features a PowerPoint presentation.

‘For Someone’ - Long Fling. Featuring Pip Blom, this is a nice piece of lo-fi indie.

‘The Green Country (New England Mood)’ - Jimmy Giuffre. It says ‘green’ in the title, but there’s something very (and appropriately) dark and autumnal going on here

You can also find this playlist on Spotify:

This month’s entry in our on-going series on Holmes Movies looks at two versions of Holmes from two greats of animation, Disney and Hayao Miyazaki:

Not just the nephew of Sir Geoffrey Elton but from a very distinguished Jewish-German academic family, the Ehrenbergs. His great-grandfather went to school with Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Poor Ben. ‘Woke’ before it was (un)fashionable to be so, caught all the same flak twenty years in advance…