The glums of August

There’s been a distinct air of slump in the Metropolitan household for the last couple of weeks. Summer is waning; the house is filthy; it’s dark at 8.45pm and counting; and the garden, which looked kinda nice in May, is now a stupid yellow dustbowl. So perhaps it’s just ennui, but we ain’t half struggling to find anything decent to watch on the telly. August has mostly been a process of saying ‘we could try this’, watching one episode, looking at each other silently, and going to bed early. For example:

The Assassin (2025, Amazon Prime). Our Lady Keeley of Hawes stars as a suddenly reactivated 50-something assassin who is also a mum. I’ll watch Hawes in the first episode of anything, but this is an effortful trudge up Cliché Mountain despite the delightful Greek locations. Speaking of which, I suspect this entire show came about because someone said ‘what if Killing Eve but also The Durrells’, which is an example of what we parents call an ‘inside’ thought. Having said that, I’d definitely watch a show in which a menopausal assassin keeps killing people because they ate the last Magnum.

Treme (2010, Now TV in the UK). David Simon’s follow-up to The Wire, about the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in a down-at-heel area of New Orleans. Because Americans don’t use diacriticals, we’re going to do you a favour and tell you Treme is pronounced ‘truh-MAY’. The first episode centres around a character (Steve Zahn) who is so fucking annoying that we couldn’t go on. Also, it’s interesting how the Hurricane Katrina story doesn’t translate very well for a UK audience. Brits can instantly glom onto The Wire’s themes of corruption, underfunding, drug wars, bad government, intergenerational oppression and tragedy. But the Katrina story adds more US-specific factors – the long-term effects of slavery, the dynamics of federal versus state government, and the ferocious impacts of large weather systems – and doesn’t really feel the need to explain them. Which is kind of fair enough; The Wire didn’t explain very much either.

Homicide: Life on the Street (1993, also Now TV). A homicide team in the Baltimore police department solve (or do not solve) crimes, while getting drunk and bitching about management. If this reminds you of something, that’s because it was based on a book that David Simon wrote and that later informed The Wire. Homicide stinks of the 1990s: all caramel slacks, soft-focus video, and that distinctive ‘90s sub-Lynchian move in which mildly odd characters are implied to have supernatural powers. (Until the very end Tobias was expecting Ned Beatty’s character to be revealed to be a ghost, which is the kind of shit you could get away with in a workplace drama in the ‘90s.) If you watched this at the time you probably loved it, but coming to it fresh in 2025 is a little more difficult. On the upside Yaphet Kotto is in it, which will remind you that Midnight Run exists and enable you to say ‘Is this going to upset me?’ every time the team is assigned a new murder. Everyone says Homicide gets better, so we might try the second episode at some point.

The Line (also known as A French Village, 2009, ITVX). A drama set in, well, a French village during the Nazi occupation. This runs for seven series, holy hell, and has very good reviews, which made the poor-quality soapiness of the first episode quite bewildering: foreshadowing dialogue (‘the Germans are not going to advance 100km in one day!’), Acorn Antiques-style dynamic close-ups, and incredibly baggy scenes that hang around for a good five minutes after they’ve made their point. I couldn’t get past the scene in which a primary school class, stranded in a field after several children had been strafed by a German airplane, were arranged by their teacher into a sort of human pyramid from which every single pair of tiny eyes could focus unrelentingly on the bloodied bodies of their friends. I’m pretty sure they train you not to do this in the ‘surprise gunship attack’ module at teacher school.

We’re not even going to try King and Conqueror (2025, BBC), because although early Medieval British/French history has SO MUCH POTENTIAL for brilliant drama, all the reviews of this one make it clear that it’s brain-dribblingly stupid. I was particularly unhappy when I heard the star, James Norton, on Radio 4’s PM chirping about how 1066 is ‘the first bit of history’. I mean, I kind of know what he means, but for Pete’s sake. Once again, our hopes for a multi-season epic based around the life of William Marshal have been set back by idiots.

Basically: when is the new season of Slow Horses starting, because we can’t take much more of this.

Letterboxd Diary

A lot of spandex and secret identities this month, starting with the grand-daddy of them all:

Superman (2025)

‘Are you alright?’ asked the Everyman staff member as I was leaving. She could, no doubt, see the tracks of my tears, my red eyes and the sopping tissue clutched in my hand. I reassured her that I very much was, although I did not stop to explain that I am old, and I cry at everything; and that there was a very good dog; and that there was also the Big Blue Boy Scout, the original superhero.

I am not, by the sound of it, the only middle aged man to have cried during Superman. I mostly blame Krypto the super hound, who director James Gunn has very wisely depicted as behaving like a real and recognisable dog, thereby making him extremely lovable and tear-jerky. Not for nothing was the film preceded by an advert for pet adoption.

But I also blame Gunn’s equally wise depiction of Superman himself. Created in 1938, Superman was the very first true superhero, the character that gave his name to the genre and is the die from which every one has been struck since, one way or another. He’s also the first superhero for most children, given his primary coloured outfit and primary coloured sensibility.

Created on the eve of the Second World War by two Jewish Americans, the sons of immigrants who had fled European antisemitism, Superman was himself an immigrant (albeit from outer space) who stood for the everyman against the wilful and corrupt use of power. In his first appearance in #1 of Action Comics in 1938, he rescues a woman from her abusive husband, overturns a wrongful conviction and unmasks a corrupt politician.

Gunn’s Superman is very much this character, but he also feels influenced by Grant Morrison’s depiction in his stand out All-Star Superman (2005). Frank Quitely’s cover to that comic depicts Superman sitting on a cloud above Metropolis, turning to smile at the reader over his shoulder. This is a direct reference to an encounter that Morrison had at a comic convention. They ran across someone in a Superman costume, perched happily on a bollard, answering questions from kids perfectly in character.

This, Morrison realised, was what an all powerful being would be like. Perfectly at ease, unafraid of anything, open to all. And this is David Corenswet’s Superman in Gunn’s movie. An alien with superhuman abilities who, nonetheless, will stop in the middle of a battle with a giant monster to save a squirrel. Possessed of the biggest stick of all, he speaks the most softly.

And this, of course, is the real reason for the tears: that I got to spend a couple of hours in a world where ultimate power was wielded not to bully and bluster but to defend and support. Escapist fantasy, of course, but there’s a lot from which to escape these days.

Not that it is a good film, strictly speaking. I certainly wouldn’t recommend it to anyone who wasn’t already a comics fan likely to squeal excitedly at appearances from Rex Mason, Cat Grant and Guy Gardner. Speaking of which:

The Fantastic Four: First Steps (2025)

Another not-strictly-good film that made me cry with joy. And also laugh at a time dilation joke as Sue Storm gives birth on a space ship orbiting a black hole, which was not a reference I was expecting in a Marvel movie.

My friend Zhenia, who is a Russian artist who dresses in black the better to match his sardonic worldview, once asked me why I watch these ‘terrible films’. The best answer I could give is that it was somewhat analogous to a mid-century suburban American Christian going to see The Robe (1953): a mixture of delight at seeing these stories in which you had steeped as a child, five feet high and luminous; and a quasi-religious experience, a ritual observance, a pilgrimage to a site of wonder.

I don’t mean this entirely literally, although there is a decent argument (Grant Morrison again) that superheroes are the modern equivalent of the pantheons of the ancient world. But it is at least equivalent to wandering through a museum full of sculptures of classical gods and heroes; symbolism, metaphor and story cast into human form.

This is also a clue to why these aren’t ‘good’ films. Like the legends of mythological heroes, they do not work as standalone narratives, because they are not standalone. They are parts of a complex and ever evolving cosmology. These films are not coherent and fully thought through works of art; like comic book issues, they are single chapters in much larger, interleaving, constantly developing narratives. Fantastic Four: First Steps is a good example of this.

‘First Steps’ initially seems like a ludicrous title. It is the fourth film of the Fantastic Four, the thirty seventh Marvel film and, even, the second appearance of Mister Fantastic in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Added to that, the film opens in media res, with the eponymous team already world famous, having taken their ‘first steps’ a long time ago, and finishes before Franklin Richards, the child born during the film, takes his ‘first steps’. It’s not, for once, an origin story, indeed, I don’t remember any explanation of the team’s powers. You’re supposed to know already.

But any Marvel film-going nerd will understand what that subtitle means. The Fantastic Four was the first superhero team created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, and was the foundation stone of the Marvel universe. This is where this whole fantastical foofaraw started.

Which is presumably why Marvel actually tried to make this more of a standalone film, set in a sci-fi ‘60s with ostensibly no reference to any of the other Marvel films. This is confusing at this stage, given that we now expect a degree of interconnectedness. Paradoxically, this means it is not independent of the rest of the MCU, because it depends on us remembering all those parallel universes from Doctor Strange and the Multiverse of Madness (2022) and the Loki TV show (2021). Another thing that is second nature to anyone steeped in comic book lore.

Those ‘First Steps’, we finally understand, are meta-fictional. This is the introduction of a fresh narrative thread to the increasingly frayed rag rug of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. And yes, there are the Fantastic Four, in the post credit sequence of:

Thunderbolts* (2025)

Also not ‘good’, although enlivened by the ever dependable Florence Pugh (and David Harbour as yet another loveably dysfunctional dad). No crying this time, either, despite the fact that it is a movie about mental illness, featuring, as it does, a Superman analogue who is crippled by depression.

This is, perhaps, a hopeful sign that the Marvel films will become more like comics. Like all pulp genres, superhero stories are capable of being mashed up with any other kind of genre and being bent to tell any kind of story. The two-dimensional characters and the fantastical settings usually mean that they are highly pliable. They don’t have to be about men who don’t know what order in which to put on their pants saving the universe again. They can be sci-fi or comedies, bildungroman or thrillers, explorations of morality or politics. They can be about mental health and reckoning with your past and families, found and otherwise. And they can end not with a punch-up, but – like Thunderbolts* – with a hug. Writers like Grant Morrison have long ago realised that you can do all kinds of things with superhero stories and, indeed, you should.

Girl on a Motorcycle (1968)

I wish I’d watched this when I was writing my piece on Easy Rider (1969) because it feels very much like a European mirror image, being set in Switzerland, France and Germany, featuring a central female character, and concentrating largely on sex rather than politics.

Like Easy Rider, it uses the motorcycle as an all-purpose metaphor for the ‘60s youth rebellion: a symbol of financial liberation, an alternative to the suburban family station wagon, a vehicle of escape from convention and regulation, of endless flight with no purpose other than the journey. An object of liberation, but also the dangerous thrill of flying beyond control, Eros and Thanatos harnessed together and chromed over in one throbbing, phallic machine.

Like Easy Rider it is also very male. Marianne Faithful’s Rebecca, the girl of the title, is depicted as a gurning idiot with nothing on her mind other than sex; nominally the protagonist, she is little more than an object to be passed about and examined by the men around her. The American title for the film, Naked Under Leather, is a big clue to what the film is really about.

Directed by Jack Cardiff (cinematographer for Powell and Pressburger on three of their films) it is, at least, frequently a beautiful film (apart from all the dull psychedelic bits) and is stuffed with some lovely footage of late ‘60s Northern Europe. Also, all of Alain Delon’s outfits are beautiful.

Speaking of motorcycles, lovely outfits and beautiful views of Northern Europe:

Diva (1981)

Luke Honey covered this recently for his Weekend Flicks, which prompted my rewatch. I loved it at the time, and then, thanks to a friend, read all the Delacorta Gorodish and Alba books. It is a prime example of the ‘80s French cinéma du look and is full of stylised, striking images: Serge Gorodish’s empty blue apartment, early ‘80s Paris at dawn, a perfectly framed and lonely lighthouse. Even the plot is largely a miscellany of outlandish elements: a bootleg of an opera performance, a motorcycle chase through the Métro, a corrupt policeman killed by a car bomb in a classic Citroën.

It is, perhaps, a little too stylised, even for the cinéma du look and I think Luc Besson’s Subway (1985) just pips it for me.

Mickey 17 (2025)

A sci-fi black comedy from Bong Joon Ho, set on a billionaire’s mission to another planet fleeing a climate change ravaged Earth, during which Robert Pattinson’s Mickey is repeatedly killed doing dangerous jobs and then repeatedly cloned in order to get him back to work. It is very obviously a satire of contemporary cultural and political inequalities and the gig economy, but manages to do it all reasonably entertainingly.

Most specifically, though, Mark Ruffalo’s performance as the preening billionaire, in which he is very clearly riffing on Donald Trump, makes me wonder at how many older films I’ve watched where an actor is lampooning a popular figure in their performance but at this cultural remove I’d just never know.

Far From Heaven (2002)

Now this is a genuinely good film, without any need of apostrophes. Todd Haynes’ version of a Douglas Sirk ‘50s ‘woman’s picture’ updates the portrayal of the period to a much more realistic milieu of racism, homophobia and misogyny. It's a splendid movie, with beautiful, period accurate cinematography (and some rear projection for driving scenes, huzzah!) and terrific performances, especially from the leads.

What’s interesting, though, is that in depicting the true, underlying cultural hysteria of the period and accurately capturing the deep, repressed emotions, it then loses the febrile narrative hysteria of so many Sirk films, which had to sublimate the character’s sexual and emotional fervour into frequently over-the-top, camp dramatic elements, which I kind of missed.

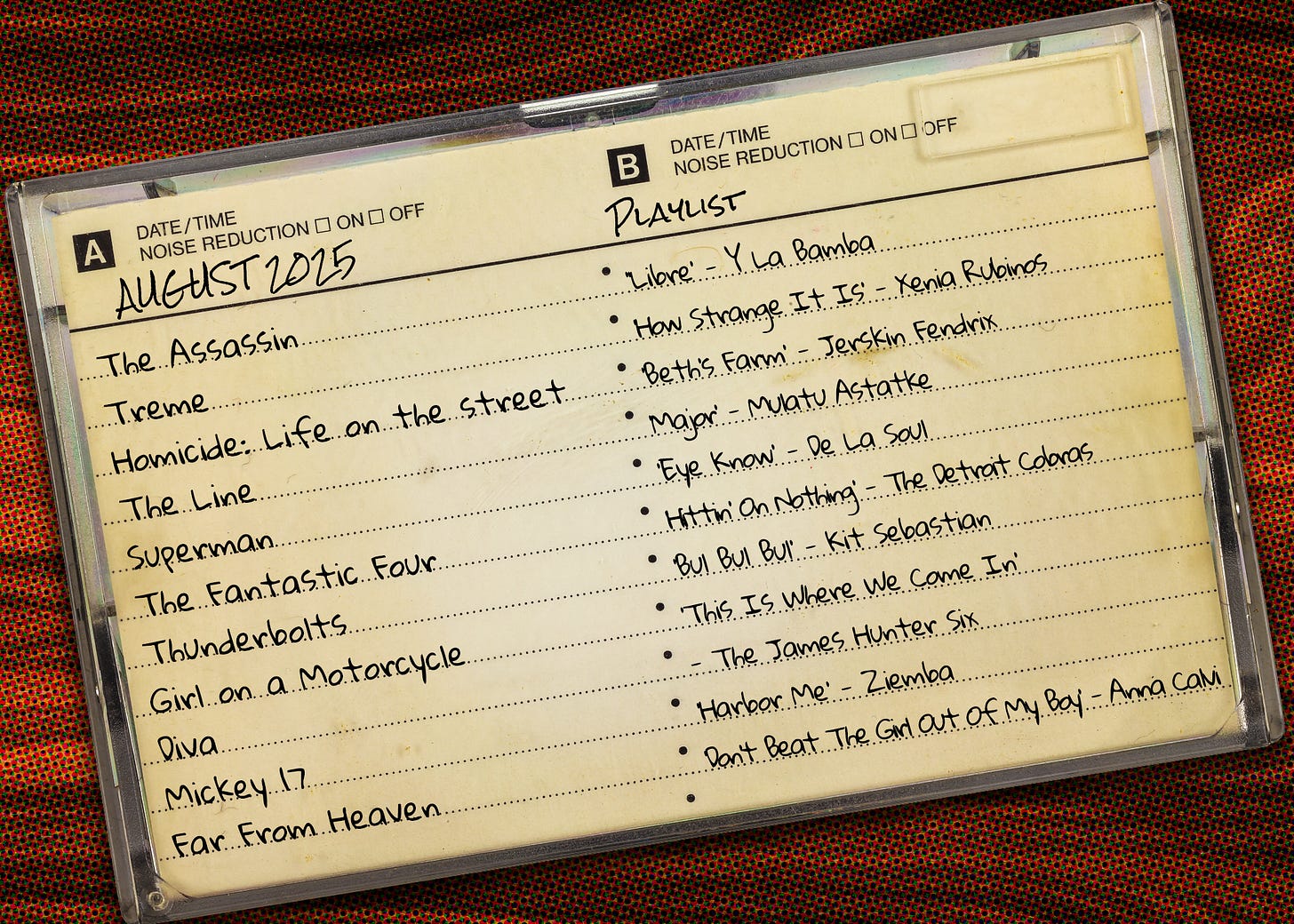

Tracklisting

Ten tracks I’ve had on repeat this month. The playlists are all on Spotify.

‘Libre’ - Y La Bamba. Something sunny and jangly to start with, as summer is starting to slacken and we can all go outside once again.

‘How Strange It Is’ - Xenia Rubinos. This has a splendidly off kilter momentum to it.

‘Beth’s Farm’ - Jerskin Fendrix. I was not expecting Emma Stone to show up in the video for this, but then I found out that he’s done soundtracks for Yorgos Lanthimos (and also for a performance of Ubu Roi, of which I thoroughly approve).

‘Major’ - Mulatu Astatke and Hoodna Orchestra. Some cheerful Ethio-jazz, just to pick things up a bit.

‘Eye Know’ - De La Soul. I don’t why Spotify decided to play De La Soul this month, but I’m very glad for it. I’ve had a lot of work on and this has definitely helped me get through it.

‘Hittin’ On Nothing’ - The Detroit Cobras. Reading the band bio on Spotify was a hell of a way to discover that lead singer Rachel Nagy died in 2022. I don’t like live music much but I do have fond memories of watching her, beer bottle in one hand, whiskey bottle in the other, somehow also holding a cigarette and a microphone, belting out RnB tracks exactly as they should be: loud and dirty.

‘Bul Bul Bul’ - Kit Sebastian. A Turkish French band from London and as groovy and splendid as that pedigree would suggest.

‘This Is Where We Come In’ - The James Hunter Six. The kind of record that could have been made at any time in the last six decades and which I’m curiously reluctant to know more about.

‘Harbor Me’ - Ziemba. Band founder René Kladzyk is apparently also a perfumer and investigative reporter. In other words, in their twenties.

‘Don’t Beat The Girl Out Of My Boy’ - Anna Calvi. A marvellously histrionic finish with some lovely big, Cure-ish drums.

The whole playlist is on Spotify here:

"In other words, in their twenties." LOL

Not only is there a new Slow Horses, this autumn, there will be Down Cemetery Road too (Zoë Boehm series) with Emma Thompson and Ruth Wilson. Can’t wait. In the meantime we can reread the books and listen to the excellent audiobooks