In

Yes, Minister / Yes, Prime Minister (1980–88)

For those of you who didn’t grow up in the distant land of Birdseye Potato Waffles, Butlins and deely-boppers: Yes, Minister was a political sitcom about a slightly rubbish government minister, Jim Hacker (Paul Eddington), and his relationships with his civil servants in the fictional Department of Administrative Affairs: Principal Private Secretary Bernard Woolley (Derek Fowlds), and the Permanent Secretary Sir Humphrey Appleby (Nigel Hawthorne).

This sounds like an unprepossessing premise, admittedly. And yet – after a slow start in which there was far too much Terry-and-June-style capering with Jim Hacker’s long-suffering wife, and a gobshite party adviser character who didn’t quite work – it quickly became entirely beloved by broadsheet-reading sitcom-watchers. Famously, it was Margaret Thatcher’s favourite TV programme, but that didn’t stop all the Guardian readers loving it too. And if you know anything about how rancorous UK politics were in the 1980s, you’ll appreciate how astonishingly good it must have been to overcome that divide.

The comedy in Yes, Minister derives from the obstacles that unelected civil servants (Bernard and Humphrey) place in the way of the people’s elected representatives (Jim Hacker), and the many serpentine ways they find to frustrate the policy agenda of Hacker’s party (which is never specified). The Civil Service doesn’t want to do anything other than maintain the status quo; Sir Humphrey’s entire job is to stall and frustrate Hacker at every turn.

Watching it from a purely political standpoint in 2024–25, it’s easier to see why Thatcher loved it than it is to see why Guardian readers loved it. This characterisation of the Civil Service as an anti-democratic red-tape nightmare is, in our current benighted era, recognisably the property of the Right: think of Dominic Cummings going on about ‘the Blob’. (There’s even a delightful bit in Yes, Minister about the ‘Euro sausage’, in which Hacker glumly announces that British bangers must henceforth be labelled ‘emulsified high-fat offal tubes’, which sounds like the sort of thing Boris Johnson used to say to get a laugh.) The other thing you quickly notice is that it has contempt for the idea that government might ever be a force for good; Hacker’s decisions are always guided by what’s best for his career.

And so it is not actually very surprising to discover that co-writer Anthony Jay was an absolutely massive Tory of the Thatcherite persuasion. That Yes, Minister achieved cross-party support despite its recognisably right-wing impulses might in part come down to events, dear boy. At the point it was first conceived in the late ‘70s, the UK was emerging from a period in which Labour Prime Ministers and Cabinet members had faced not only passive-aggressive Civil Service foot-dragging, but active attempts to smear them as Soviet agents and, briefly, an attempted coup by some aggressively bibulous members of the armed services. To add insult to injury, the Civil Service at this time was populated by men who had all been to the same schools and one of exactly two universities, who all knew each other, and who all looked horrified if you used the word ‘toilet’. It was perfectly logical that both Labour partisans and Margaret Thatcher – who was regarded as distinctly below-the-salt by many in her party – should have been equally irritated by it. Both ‘70s Labourites and ‘80s Thatcherites were, in their own ways, revolutionaries, and revolutionaries don’t tend to like civil servants very much.

But of course, whittering on about the politics of it misses most of the point. (Hello, and welcome to The Metropolitan.) The sheer joy of Yes, Minister lies in the brilliant writing by Jay and Jonathan Lynn (whose bizarrely multitalented CV runs from ‘On the Buses’ to My Cousin Vinny), and from an absolutely stellar cast. Eddington, Hawthorne and Fowlds are all consummate comic actors, able to wring laughs from a lift of an eyebrow and a murmur. Hawthorne – whose catty, camp Sir Humphrey now reads as extremely gay – was the breakout star, but Eddington’s portrayal of Hacker’s desperate, eye-flickering, rat-like scheming is absolutely delightful too. And let’s not forget the brilliant title sequence featuring terrifying cartoons by Gerald Scarfe. We started watching it because of a happy accident (the 1983 Christmas Special popped up while we were flicking through our cable channels, which is something we hardly ever do), but we were so delighted and amused that it was impossible not to watch more.

Out (not in our usual sense)

Cigarettes

David Lynch (1946–2025)

Tobias Sturt: I’ve only written about Lynch from something of an angle in The Metropolitan, as he always felt too big to tackle head-on. I wrote about Twin Peaks in my piece ‘Big Night In’ and covered his extraordinary version of Dune when I wrote about Doctor Who and Passage To India in ‘Dr Aziz and the Caves of Androzani’.

I’m bound to return to Lynch, not least because I haven’t even tackled Blue Velvet yet, but most of all because he was one of the great artists of my lifetime. A few years ago, trapped in Philadelphia by a snow storm, Adam Frost and I took a walk to find where Edgar Allan Poe stayed when he was there, and the house David Lynch lived in when making Eraserhead. Poe and Lynch are two of the great American artists, both shaped by the dream of America and both uniquely able to articulate its core horrors and fascinations.

Anyway, the thought of there never being any new work by David Lynch is extremely depressing and I wish he’d stopped smoking, but then, perhaps, without all those little burnt offerings, the dreaming smoke curling up into the unknown, the smouldering tobacco whispering to him, we would never have had what we got.

Shake it all about

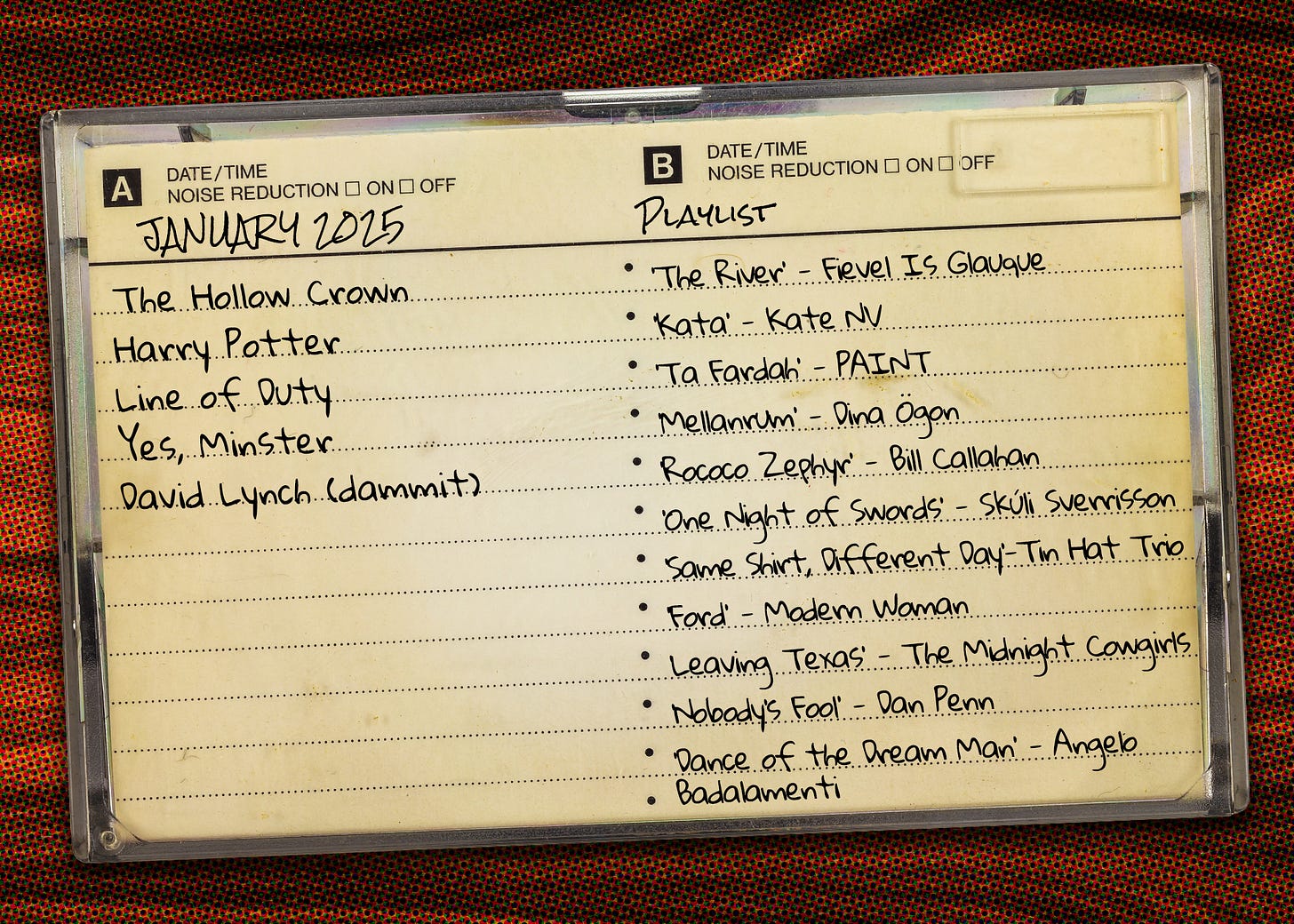

This month’s playlist: ten stand-out tracks that Tobias has enjoyed this month. Actually, given that we did a Christmas playlist in November and no playlist for December, the last three months. Whittling this down wasn’t easy.

The playlists are all on Spotify.

‘The River’ - Fievel Is Glauque. Belgian/American post-punk jazz pop and featuring a reference to the animated movie An American Tail (1986) and the splendid word ‘glauque’. It’s like someone is making music specifically for The Metropolitan.

‘Kata’ - Kate NV. And straight into ‘80s inflected Russian electro-pop. Always fascinating the music of one's youth being reinterpreted and reinvented by a new generation.

‘Ta Fardah’ - PAINT. Solo track from Persian American artist Pedrum Siadatian, sometime of the Allah-Las. Not the Canadian band of the same name.

‘Mellanrum’ - Dina Ögon. Back round to Scandinavia on our musical world tour for some Swedish lo-fi soul/hip hop.

‘Rococo Zephyr’ - Bill Callahan. A beautiful little song with a title featuring two of the most beautiful little words in English: ‘rococo’ and ‘zephyr’. Splendid work.

‘One Night of Swords (feat. Laurie Anderson, Anthony Burr)’ - Skúli Sverrisson. More dreamy Scandinavian pop, with a little added New York avant garde courtesy of Laurie Anderson.

‘Same Shirt, Different Day’ - Tin Hat Trio. We wrote about Tom Waits this month, and he’s collaborated before with this San Francisco trio, who sound like Waits has been put in charge of the Penguin Cafe Orchestra.

‘Ford’ - Modern Woman. Included partly for the Capri owning section of The Metropolitan audience (that’s you, Goodfellow), but they feature a Cortina in the video, which is just as good an option.

‘Leaving Texas’ - The Midnight Cowgirls. A terrifically hooky piece of rockabilly / country / post-punk.

‘Nobody’s Fool’ - Dan Penn. A glorious piece of ‘70s blue eyed soul. I guarantee you will be whistling this for the rest of the week.

‘Dance of the Dream Man’ - Angelo Badalamenti. An extra track this week, and you know why.

Other comfort watches this month were Line of Duty, Shakespeare and Harry Potter:

My father, an actual civil servant, also loved the show. it takes a special kind of genius to satirise a group of people and have those same people laugh in recognition. (On similar lines, W1A is how I explain higher university administration to people outside that world)

I went back to read the Dr Aziz… piece, and fell about laughing at “if you ever wondered what Robert Glenister might have looked like as a member of Bucks Fizz, now’s your chance to find out”.

The thing that I love now about Yes Minister and other sit coms of that time is the way you can see them trying not to laugh and break character. It’s more like theatre, and everything now is so very glossy. I’m not being mistily nostalgic as there was a lot of utter rubbish as well, but it does come across as more “conversational” with the viewer somehow. I think it’s why I love Be Kind Rewind, where they go about Sweding all the films— all the cardboard box and chicken wire remakes are so imaginative and theatrical in just the right way.