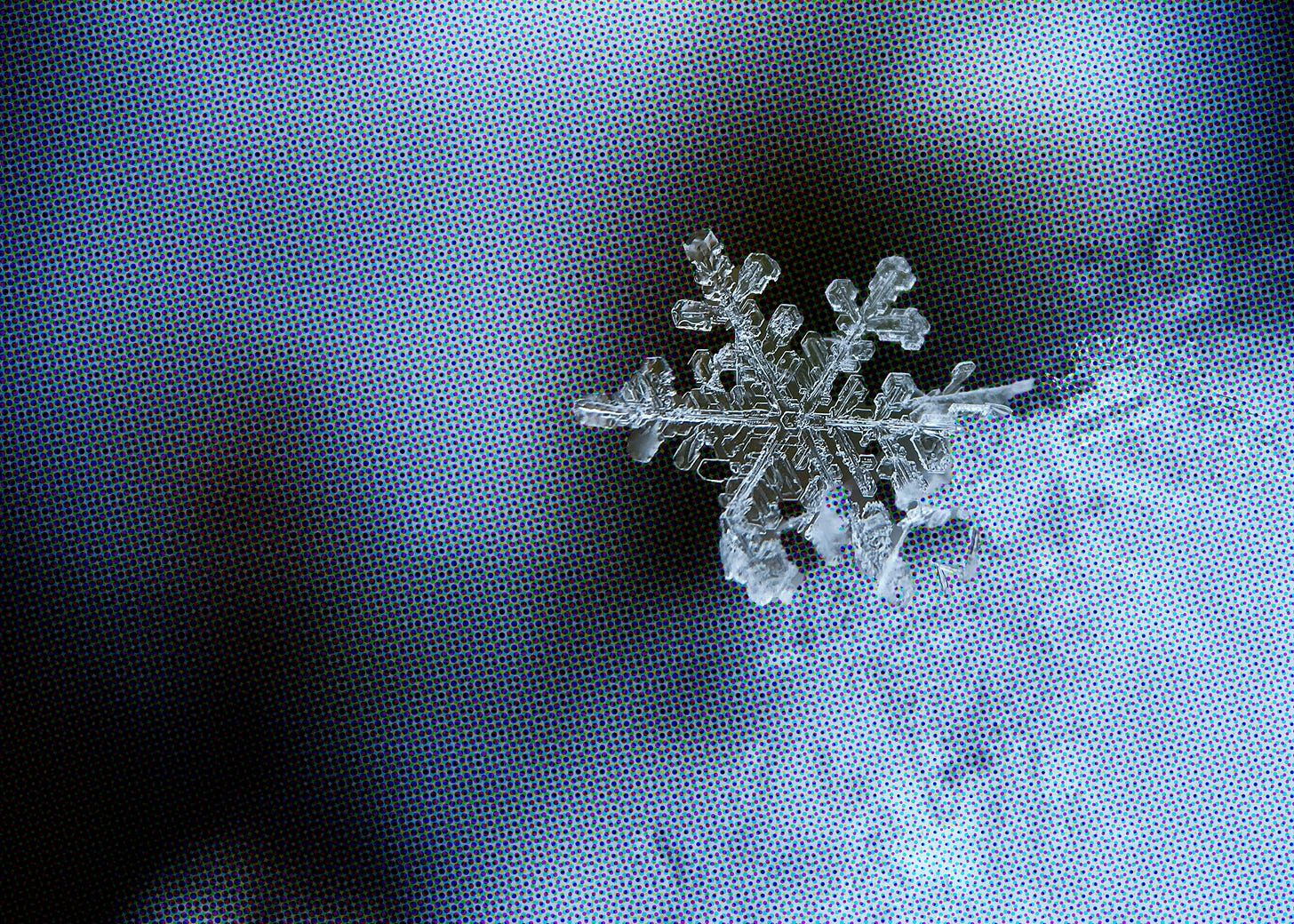

Hearts of ice

A catch-up with Miss Smilla

Re-reading old favourites after a long break entails a certain amount of mild peril, like reconnecting with friends from long ago. Instead of everything being relatively familiar and easy, sometimes you find yourself having no fun at all. You get bored, maybe surreptitiously check your phone; you begin to wonder who this weird stranger is, and why you ever liked them.

So it was when I recently re-read Peter Høeg’s Miss Smilla’s Feeling for Snow (1992), a novel that tore through the literary fiction shelves of ‘90s bookshops like a fire-tailed comet. The first page of my copy informs me that I bought it in 2000, and back then I absolutely loved it: the descriptions of snow and ice, the caustic and bloody-minded heroine, the high violence, the twisty plot, the foreign-ness of it, and the ethereal glimpses of Greenlandic culture. Of course, I was a largely different person then. When we find that old friends have turned into weird strangers, we tend not to remember that they could be thinking the same about us.

Meanwhile, 2025-me foot-dragged my way through Miss Smilla like a toddler in a supermarket, stopping occasionally to throw myself to the floor and scream (metaphorically. Well, mostly metaphorically.) I was within touching distance of the end when I found myself facing a dense 2000-word passage describing the layout of some damned part of the damned ship that the damned heroine is on, and suddenly all the will just went out of me. I was done. I marked it as ‘read’ and bought myself a proper thriller (the first of Daniel Silva’s Gabriel Allon series, if you’re interested; the kind of book you can happily read while under heavy sedation.)

I then did what every right-thinking human does after suffering a defeat. I went looking for post-facto excuses. I found what I was looking for on Goodreads (people sneer about Goodreads, but I’ve always found it useful) in a cathartic review by ‘Virtuella’:

The larger part of the book is both boring and annoying. I saw it described as a mixture of thriller and philosophical meditation, but I found it neither thrilling nor thought-provoking. … Too many obscure plot elements (heroin smuggling by antiques dealers, Nazi collaboration, code cracking, exotic parasites, radioactivity, x-rayed mummies, meteorites that may or may not be alien life forms, a demented musician, a sado-masochist couple, gambling, murder, arson, really, he stops at nothing), too many random asides, too many characters. It was all so confusing, such a jumble of stuff that the story never had a chance to build up any real tension simply for lack of focus. What didn't help were the lengthy descriptions of, for example, the contents of cupboards or the layout of the ship, a corridor here, a door there, a light switch, move this way, move that way, duck into an alcove. There is only so much cat and mouse that is interesting to read about, then it becomes dull.

Almost all of this, in my opinion, is entirely correct, for the following reasons:

Miss Smilla absolutely does not work as a thriller. I realise this is a bold statement to make about a book that sold over two million copies, but we are where we are. One of the differences between millennium-me and 2025-me is that 2025-me has read hundreds of thrillers; and while I’m all for a bit of experimentation, Miss Smilla is just incompetent on this front. It has 200 metric tonnes of plot, only three of which are pertinent to the supposedly central question of who killed Isaiah (the Greenlandic child whose death opens the novel). It starts like a thriller; the first quarter is an imperial stomp. But after that the pacing is wilfully erratic. All the thriller energy bleeds out in the quiet shadows of a thousand meandering side-missions, and by the end you quite simply no longer care who did it.

It is near-impossible to keep track of all the characters. Admittedly (if you’re not Scandinavian or Greenlandic) this is partly a ‘foreign names’ problem of the kind familiar to any non-Russian who’s tried to read War and Peace; but even allowing for that, two-thirds of the characters are exactly the same person. ‘Which sinister oddball is this again?’ you ask yourself when confronted with yet another taciturn technologist with a substance abuse problem and a distressing sexual kink. I’ve never met any Danish or Greenlandic people, but it seems unlikely that they are all like this.

A lot of effortful choreography — ‘A corridor here, a door there, a light switch, move this way, move that way, duck into an alcove’ — is an occupational hazard with thrillers, to the extent that I can only assume some readers (men. I’m talking about men) must enjoy it. I — a woman so bad at visualisation that I once had to be sympathetically guided out of Hampton Court Maze by my three-year-old child — do not enjoy it. I take no more information from these passages than I do from the dust cloud reading ‘BIFF!’ in a cartoon. I just flip past them, find out who’s still alive, and move on. If you want me to understand the geography of a fight, you should include a bloody diagram. Otherwise you’re just being discriminatory.

But even after giving up, and then retrofitting a decent excuse for giving up, my brain didn’t want to leave it there. I don’t usually suffer from DNF (Goodreads slang for ‘did not finish’) shame; I recently sorted my Kindle by ‘Unread’ and discovered hundreds of books I don’t remember starting, let alone not finishing. Literally whatever; who cares. But Smilla wouldn’t leave me alone. I thought I was done — friendship over! — but she kept jabbing me in the back of the head with her screwdriver, which is how she expresses affection because she’s an irritating twat.

The thing is, you can make a lot of cases for the ways in which Miss Smilla fails. You can say it doesn’t work as a thriller; you can say it needed a bloody good edit; you can (as Virtuella does in their review) point out all the hundreds of improbable occurrences that keep the heroine alive. (A super-rich and well-connected magic dad, eh? There’s lucky.) But you can’t — not really — argue that it’s a bad book, because there’s something irreducibly wonderful about it. Through grace and commitment and sheer bull-headedness, it demonstrates the right to exist in its singular form. Even this time around, when it was incredibly hard going because I was bringing all the wrong expectations to it, there were passages I found spellbinding.

Høeg — who seems charming in a thoughtful and restrained kind of way — has talked about how young he was when he wrote it. With one novel and a collection of short stories behind him he had built up an intimate audience of around 5000 readers in Denmark, all of whom completely ‘got’ him. When his highly individualistic, self-confident style was suddenly projected across the globe, it was inevitable that it would land differently. He talks generously about wishing he had allowed more edits; at the time, he told publishers — including his putative US publisher — that if they touched one word, he would refuse to go ahead. They all backed down. You have to be very young or very talented to pull off that stunt, and Høeg was both.

In every piece about Miss Smilla you will find a reference to Nordic Noir, along with the assertion that Miss Smilla started it. Maybe it did; I don’t know. (I’ve never read any Nordic Noir. It seems to major in sexual violence, so I’ve avoided it.) I guess the defining features of Nordic Noir books are that they’re set in Scandinavia, they all involve murders, they have female protagonists, and everyone wears lots of stylish layers. If so, you can see where the assertion comes from.

The problem is that, as previously discussed, Miss Smilla is a very so-so thriller, which suggests that — like me on second reading — a lot of people missed the point. That’s just not what it’s doing. (If you want a highly effective ice-bound thriller with an ultraviolent Inuit protagonist of genius-level scientific intellect, I am once again recommending Lionel Davidson’s Kolymsky Heights.) Thirty years after unleashing this ‘thriller’ on the world, Høeg confessed that the thriller superstructure was imposed almost as an afterthought. The ‘rationale of the plot’ was a ‘thin illusion’ created to give the reader ‘a sense of satisfaction’, he said. The plot involving Isaiah’s death doesn’t work because that wasn’t the book Høeg had actually written.

The real Miss Smilla is many things. It’s an exploration of the tensions that arise for individuals who must code-switch between different cultures. It’s a portrait of the psychology of place and connection. It’s a political polemic about the relationship between Greenlanders and Danes, two entirely different nations unhappily yoked together. It’s a travelogue; it’s anthropology; it’s epigenetics; it’s an ice sculpture. It’s a curiously ‘90s artefact, like Dave Eggers’ A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, a post-postmodern curio born of the sense of possibility that existed in the West at that time; a playful, hard-headed decoupage of politics and culture and science and maths and fiction and sociology and genre and violence and biography, because why not? It’s just not a thriller.

It’s also a romance, although again I don’t think it’s a very effective one. But even that — the bloodlessness of it — is interesting. The relationship between Smilla and The Mechanic feels animatronic; who is this man, and why do these characters fall for each other? You get the feeling Høeg doesn’t know. He has said ‘there are no “real” characters with a “real” psychology in books; they are only language. They are the linguistic illusion of characters.’ This seems like a dull admission for a novelist. It might be technically true, but everyone from Lizzie Bennet to Mantel’s Cromwell would like a word. Does it mean he made little effort to write characters that feel psychologically plausible because he had already decided it was a silly endeavour? Or that he tried his best and failed? In the same interview he says that Smilla is simply Høeg, but female; ‘Smilla was an attempt to give voice to the female in me.’ This feels like a more honest explanation of what happened, and how he produced such a startling creature. It would certainly explain the scene in which Smilla inserts her clitoris into her partner’s urethral meatus, an image that has leapt unbidden into my head and made me go ‘aaaargh’ for a quarter of a century.

This close association between Høeg and Smilla feels key; a singularly stubborn man with a clear vision, unusual gifts and manic self-belief created not just a heroine in his own image, but a whole infuriating, brilliant book in his own image. If you’re willing to pick a fight with all three simultaneously then you have more in common with Hoeg-Smilla than I do. I couldn’t bear Smilla this time around; she’s mean and sarcastic and bitter and pointlessly hostile like… well, like me around the year 2000, which was probably why I liked her then. But she’s unforgettably strange and distinctive.

Høeg has such a fearless intelligence that you can’t pick any holes he hasn’t already picked. He — like his alter ego Smilla — has already processed and accepted the possibility of failure, and decided to press on anyway. Like the existentialists, the young Hoeg-Smilla conceives of freedom as not doing what you want, but wanting to do what you can; they despise the childish mewling of people who want things to be easy, ‘the particularly Western mixture of greed and naivete’ (as Smilla says in the book). Talking about the blank walls of information that erupt into the text — great treatises about the composition of ice and the administration of shipping and the chemical structures of minerals — the older Hoeg says these have lost their appeal to him since the advent of the internet. Their purpose, he says, was essentially poetic; they were valuable because they were rare, because he’d had to visit specialist libraries in Copenhagen to dig them out. Now that such information is easily available, it no longer speaks of effort or rarity, and he wouldn’t do it again. This, perhaps, is why I was impatient with those passages this time around. In the ‘90s, trapped on the Tube or on a commuter train, I would read a whole daily newspaper from beginning to end, starting with the national or international headlines and making my way through industrial news and business and comment and arts and sport. I wasn’t interested in all of these things, but it was either that or the novel in my bag. Today, information that I haven’t actively sought is more likely to be the result of sponsored advertising or incorrect search results; it is an intrusion, or an indication of failure, and I have become habituated to fending it off.

Miss Smilla’s ending is famously unresolved. In some moods Høeg wishes he had given the book a less ambiguous final paragraph, one that actually tells you what happens; ‘Today, I feel there is a certain disrespect for the reader in the ending.’ But at the same time, he wouldn’t change a thing. Miss Smilla is what it is. If he were to be transported back in time he would simply be the young Peter Høeg again, making the same mistakes, or similar ones. If he were to rewrite it now, approaching his eighth decade, it would be an entirely different book. Anyway, the faults don’t matter; or rather, the fact that the book has flaws is a part of its value, and why few people can read it without wanting to say something about it or think about it further. And what better reasons are there to read anything?

For more chilly investigations, there’s Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air:

I’m all for re-readings, just not novels that begin with the diagram of a family tree

Hmm. I LOVED that book when I first read it, and I would have put good money on it being that I did so long before 2000. Have you seen the film? I liked that less, but I still enjoyed it. It was, I think, the last film for the girl from the remake of Sabrina, who dropped from the world until she resurfaced as someone’s mom in Madmen, the most loathsome show about loathsome people, except perhaps the U.S. version of House of Cards. I can’t remember her name. I guess I have to google it. brb. Julia Ormond.

Now, of course, you have me curious how I’d react to a re-read of it. I don’t recall being intrigued by the plot so much as by the shit inside Smilla’s head. She was on the outside, always observing and synthesizing what she observed. And she saw what others did not want her to see, which I also related to. And she was dangerous as a result. I liked the power that gave her.

The best example of a book I LOVED when I was younger, but was bored by when I returned 20 years later was Forester’s The Razor’s Edge. I’d read it first one summer between college semesters and was so fixated on how much it got me with its yearning. So much so that I was surprised by how much I did not give a shit about Larry or Sophie or Isabel the next time I slogged through it. The Great Gatsby for me is similar. Who fucking wants to deal with Daisy? But Luhrmann’s remake was interesting in its stylization.

I don’t have the adrenaline for thrillers anymore. I listen to audiobooks of history, and since I know the outcome, I’m not as disturbed by the pace of events.