How to get into Hogwarts using a modem

How fantasy novels prepared us for the Internet (and vice versa)

There wasn’t much to do at boarding school in the 1970s. There was only one TV in the school and we weren’t allowed to watch it. There was, towards the end, a BBC Micro computer, but it wasn’t connected to anything. The only entertainment available was either bullying other children or hiding from the bullies. I spent a lot of time hiding. And reading. Books were the surest escape-hatch I knew, a way to reach somewhere less alarming or more distant, Wonderland or Oz, Narnia or Middle-earth.1

Which made me wonder how, 20 years later, J. K. Rowling made a boarding school (albeit a magic one) the great escape for a whole new generation. Especially given that they had the internet to waste their time on.

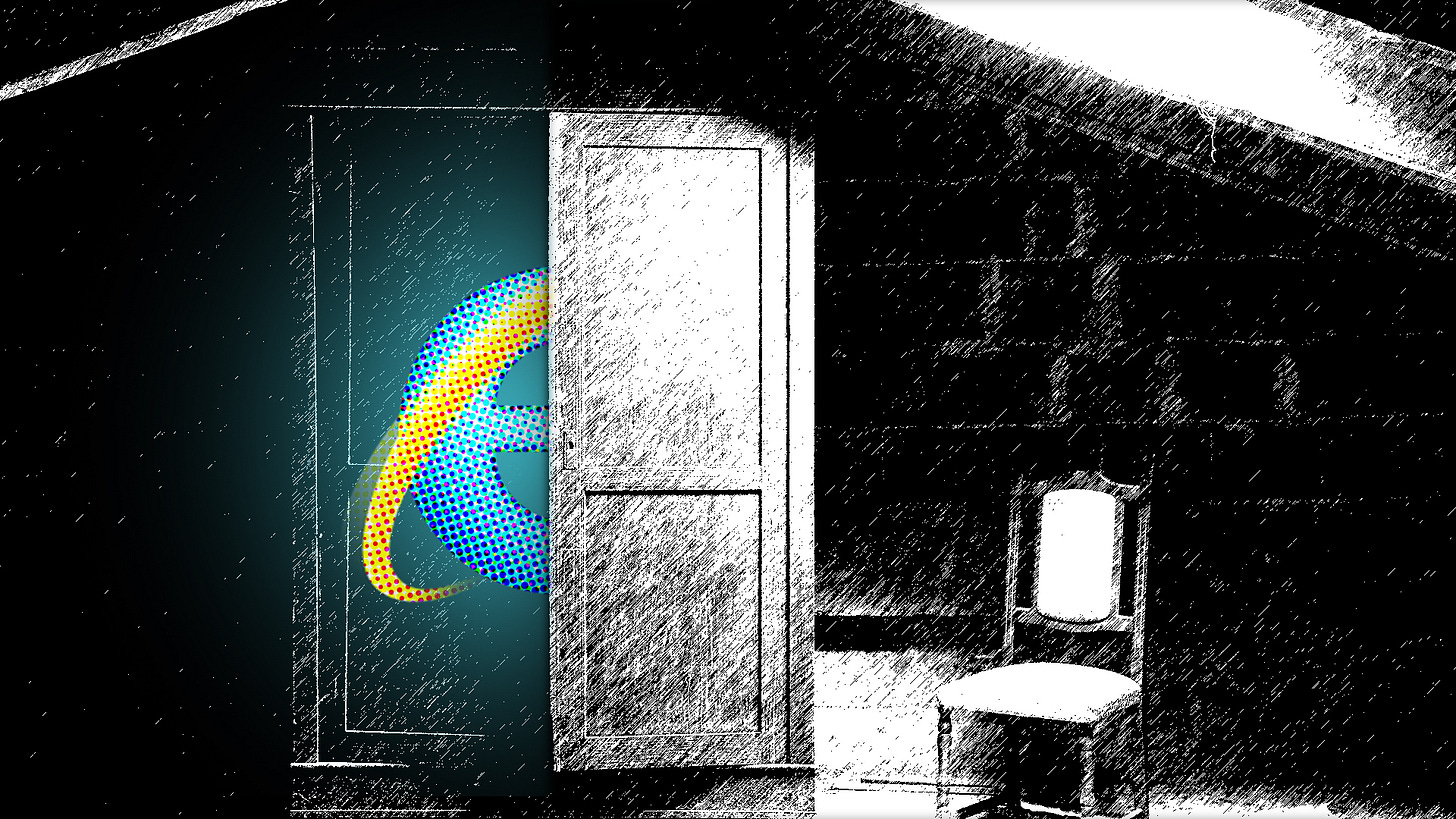

In her book Rhetorics of Fantasy Farah Mendelsohn proposes four kinds of fantasy story. ‘Immersive’ fantasies are set in an entirely fantastical world. ‘Liminal’ fantasies describe the kind of magical-realist mucking about where strange things happen and no one seems to notice. In ‘intrusive’ fantasies the fantastical intrudes upon the real and weirds out the straights. And in ‘portal’ fantasy, characters travel from the ‘real’ world into a fantastical one.

There are many kinds of portals into fantasy: everyday things like rabbit holes or wardrobes, or even just weather (tornadoes that whisk you away somewhere unexpected) or landscape (a path through a woodland or a magical cave).

Or a children’s book, of course; in itself a welcoming and reliable door into another world.

Portal fantasies are common in children’s literature. In fact, many of the best known and most inescapable are portal fantasies: Alice tumbling down the rabbit hole into Wonderland or climbing through a mirror into a chessboard, the Pevensie children processing in an orderly, middle-class manner through a wardrobe into Narnia, Milo pedalling mournfully through the Phantom Tollbooth and Dorothy being plucked through the air to Oz. You could even make an argument for the Darling children travelling to Never Never Land.

They’re an obvious choice for a children’s fantasy because they mimic the mental experience of play and make-believe, the sense of being in another, imagined world – even if it is just a toy shop with miniature boxes and plastic coins – before returning to the humdrum for tea.

They allow the child protagonists to play at being adult, performing heroic, legendary deeds (talking to animals, bargaining with wizards, killing witches), in a world where there aren’t irritating human adults to inconveniently question the heroic potential and cosmos-saving abilities of small children. Indeed, all parents are removed from the picture from the off, lest they hinder any other-worldly adventuring. The Pevensies are evacuated, and Dorothy Gale lives with her aunt and uncle, for instance; both are able to play at the process of growing up after their parents’ death, to become active beings in the world.

But the coming home is crucial too. The children may play at being adults, in the case of Pevensies even growing into adulthood as monarchs of Narnia, but they always return to the safety and comfort of childhood at the end. The portal opens both ways; danger may be in the offing but a safe return home is promised.

Portal fantasies have much in common with boarding-school stories, in fact. The child is carried away to an unlikely and discombobulating land, where the customs are arcane and often barbaric, and where they are expected to behave as an adult, independent and self-reliant, and to battle for strange victories like house cups or rugger caps, with only the end of term as a shining grail perceived dimly, as through a dark wood.2

At least one much beloved children’s book manages to combine both portal fantasy and the boarding school story: Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.3

Back in the late ’90s, around when Harry Potter was released, portals were all the rage. The world wide web was a new, almost occult experience, and a lot of people were extremely nervous and confused about going online. ‘Web portals’ were websites of curated links, news and directories that acted as starting places for novice users, the on-ramps to the information superhighway, the magical door to the internet.

Harry Potter was hailed as the saviour of children’s literature: the thing that would finally get little boys, especially, to turn off the TV, put down the action figure and pick up a book. But it was also an internet phenomenon. Not only in that, appearing in 1997, it was perfectly timed to take advantage of the new connectedness of the world and of its readers, but also in that it so perfectly mimicked the internet experience of those readers. The web portal was the Platform 9¾ of their online journey; the grinding and howling of the modem was the shrieking of an extraordinary engine that was about to whirl them away to a new magical world.

Like fantasy worlds, the internet is a strange mixture of the very public and the very private. Crouched in the cupboard under the stairs, or in the distant loft where the old wardrobe was kept, you could enter a land where your mighty deeds were known to the whole world (but not to the Muggles watching TV in the living room); where your name was legend, though it wasn’t your real name, which had magical power and must be kept secret. Here you could find your band of adventurers, play at being a hero, at changing the world, at being consequent in the world. And decide what house you would be in at Hogwarts.

To say ‘play’ is not to denigrate. Play is fundamental to being human: it is how we practise being human, how we perfect it. The use and action of imagination in play is one of the most important human activities. What we discover in play shapes us as people, makes us who we are. We may leave the fantasy world behind but the adventures we have there change us.

This is, after all, the classic hero's journey. The adventurer returns home victorious, but changed. They bring back with them the lessons they have learned and apply them to the real world. We may leave but the fantasy world follows us back.

The Harry Potter stories may start out as portal fantasies, but they very quickly become intrusive ones, as struggles and insurgencies in the magical world begin to bulge in on and finally invade the ‘real’ world. And as above, so below. The generation that spent their childhoods arguing online about what Hogwarts house they would be in have escaped parental control for good through the simple expedient of growing up. And the lessons they learned alongside Harry, Ron and Hermione have changed them. As have the lessons they learned on the internet. And now those experiences are being applied in the real world.

Dumbledore’s Army and the Death Eaters are among us now. The internet is no longer the fantasy world we approach through the magical portal. Our world has become enchanted, alive with connection, our fictional selves inextricably enmeshed with the real. We are immersed in the fantasy; it is no longer fantastic.

The way is closed. We can never go home again.

Next week: In our new feature ‘Can We Show The Kids?’, we run the rule over Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Is this Gen X favourite fit for Gen Z?

Although, locked up with 70 other public school boys in a crumbling Victorian pile, the ordeals of Frodo and Sam trapped in Cirith Ungol with Gorbag the orc were more applicable to my lived experience than is entirely comfortable.

In fact, one might gain an insight to a certain kind of adult who attended boarding school if one thinks of them as a child who once ventured through a magical doorway into a world of monsters and mystery and never found their way back. They have only been playing at being adult this whole time, ever looking, looking for that doorway back to childhood where they can be comforted, nurtured, loved.

You had read the title of this piece and knew what was coming, although I might have easily have been thinking of Diana Wynne-Jones’ Charmed Life, a favourite of my own childhood and, no doubt, since we are of the same generation, J. K. Rowling’s. It’s certainly one of the many books that influenced Potter. In fact, Charmed Life rather splendidly features a sort of reverse portal fantasy, as we experience ordinary girl Janet’s arrival from what appears to be our world from the point of view of the children at a sort of boarding school for magicians, a world that is initially terrifying to her but which eventually becomes an exciting adventure.