We were raised by Puffins. With three TV channels and no internet, for long stretches of our lives reading was the best (and sometimes, the only) way to pass the time. Here we return to the books that made us and analyse what makes them great.

Tintin, Captain Haddock and Professor Calculus (and Snowy the dog, of course) are on their way to Sydney when they are offered a lift there in the personal jet of millionnaire Laszlo Carreidas. En route, however, the plane is hijacked and flown to a remote Pacific island where their old enemy Rastopopulous is planning to hold them hostage and force Carreidas to hand over his fortune. Naturally Tintin, Snowy and Haddock foil his plans, in the process discovering that the island isn’t just a base for international criminals but is also for visitors from far further away: flying saucers!

Complicated stories

Do I need to introduce intrepid boy reporter Tintin and his white fox terrier Snowy (or Milou for our mainland readers)? You can probably swear along with Captain Haddock (“Billions of blue blistering barnacles!”) and are all too familiar with Calculus’ strange contraptions and the comical incompetence of Thompson and Thomson.

Created in the late ‘20s by Belgian cartoonist Georges Remi (his pen name is his initials reversed, as they would be pronounced in French: R. G.), Tintin was still default reading for kids fifty years later, when I started obsessively reading them in the 1970s. A comic you were allowed to read, an easy birthday present, within the value of even the smallest book token.

By why? What was the continued appeal of this tween-the-wars character from a world of steam trains, obscure European princedoms and blank spaces on the map? What is his continued appeal, because he’s still there, in the Amazon top selling mystery comics for kids, one hundred years later.

One reason is undoubtedly that these are classic adventure stories. Hergé himself read the great adventures stories of the nineteenth century as a boy: Robert Louis Stevenson and Alexandre Dumas, and the stories he wrote for Tintin are full of classic pulp tropes: treasure hunts, lost civilisations, sinister conspiracies and international criminal masterminds. There are secret passages and disguises and plenty of fisticuffs and the occasional little brush with the supernatural. And cliffhangers. A lot of cliffhangers.

The Tintin stories were originally serialised in weekly comics and even in the collected albums you can feel that breathless pulse, the narrative drive that keeps the reader in suspense between issues and drives them forward in the story. In Hergé's post-War Tintin comic, the stories were serialised two pages at a time, and the rhythm persists, with mini-cliffhangers often at the turn of a double page spread, pulling us to turn the page and see what happens next.

Of course a lot of those tropes rely on the culture that spawned them, a time of slow news and slower travel, of landline telephones, prop-driven planes and some mystery still out in the far corners of the globe. This world was recognisable to me, as a child of the ‘70s, but it was vanishing. The last completed story was Tintin and the Picaros in 1976, and Hergé never finished the final story Tintin and Alph-Art before he died in 1983; perhaps it's just as well. By the ‘80s that world was finally disappearing for good.

Hergé adapts that world, of course. Steam trains go electric, planes sprout jet engines, small European kingdoms fall under the control of communist dictatorships. Tintin goes to the moon. The thing I loved about Flight 714 to Sydney as a child was that it featured a UFO. This was yet more modernisation, of course. UFOs were largely a post war phenomenon, a folklore of the space race and Cold War paranoia. Tintin had already beaten Neil Armstrong to the Moon in the 50s, extraterrestrials were the obvious next step.

Yet even as they modernised, the stories still possessed inheritances from their original culture. The aliens in Flight 714 to Sydney have been visiting Earth for millennia and were worshipped by the ancient human inhabitants of the islands as gods, all of which sounds extraordinarily reminiscent of another book of 1968, Erich von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods. Chariots of the Gods, which proposes that various ancient civilisations were founded by aliens, who helped build the Egyptian pyramids, the Easter Island heads and the Nazca lines, is founded on the racist, colonial, ahistorical assumption that the indigenous people were fundamentally incapable of having built such monuments. It is a direct descendant of Victorian theories of Welsh princes settling America or Atlantean refugees building pyramids everywhere.

That adventurous world of Tintin is full of such assumptions. It is a world in which a young white man can go anywhere he likes around the world and fix how the people he finds are living. The plots frequently hinge on unconsciously bigoted assumptions: Tintin astonishes a group of Incas in Prisoners of the Sun (1949) by predicting an eclipse that he read about in a newspaper, in Tintin in America (1945), the Native Americans are easily duped by a gangster, and then there’s Tintin in the Congo (1931).

The very first Tintin story, Tintin in the Congo is very much a product of its origins. By the time Hergé was writing it, colonial Belgian Congo had been under the control of the Belgian government for twenty years, the preceding direct rule by King Leopold II of the Belgians having been deemed too horrific even for the other nineteenth century Imperial powers.

Hergé does not, at least, give us Tintin in the Heart of Darkness, the boy reporter heading up the river to find Captain Haddock, who has gone mad in the jungle, his methods having proved ‘unsound’. There is no mass murder or the chopping off of hands. But there is a reason that this story very definitely isn’t in the Amazon best of lists. Indeed, there isn’t even an English language version easily available. It reflects ‘opinions of its time’ and the visual depiction of the Congolese is disturbingly cartoonish and minstrely.

Hergé did re-edit some of the story of Tintin in the Congo later, but not the depiction of Africans. After all, he himself had opinions of his time. He was cleared of actual collaboration with the Nazis after the Second World War, but the Tintin strip had continued to appear in a Nazi run paper throughout the occupation. Tintin began as a strip for conservative Catholic newspaper supplement for children Le Petit Vingtième and Hergé himself was evidently an instinctively conservative child of colonial Europe.

But on the other hand Hergé and his background also gave Tintin his instinctive defence of the underdog in the face of oppression. Tintin makes friends wherever he goes in the world, usually with the down-trodden and abused, and his enemies are almost always abusive authority figures, whether state secret police, criminal masterminds or corrupt businessmen like Rastopolous in Flight 714. And the thing that most shocks Tintin about Rastopolous’ plan is that he’s intending on killing all the local rebels he’s tricked into working as his stooges. Tintin, the boy reporter, is one of the little guys himself, and always fights on their behalf.

Clear lines

But what I really loved as a child, and what I still love now, is the art. The small matter of Hergé being one of the greatest cartoonists of all time.

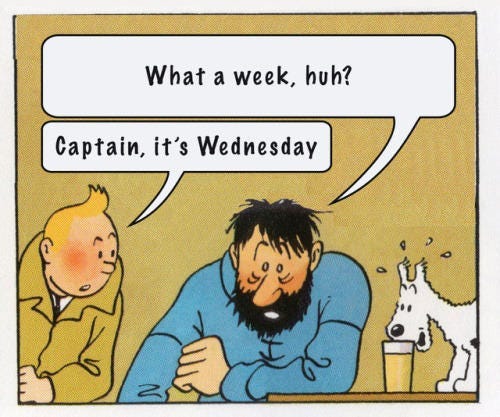

Let’s talk about the meme.

What’s annoying about this meme is not the usual misuse and misrepresentation of the characters (like the awful pissing Calvin) - the dialogue is actually pretty believable for both Haddock and Tintin, especially this early version of the Captain (the frame is from the story in which the two first meet, The Crab with the Golden Claws). No, it’s the speech bubbles. They’re the wrong way round. Tintin speaks second, so his bubble needs to be to the right of Haddock’s, fitting our read order.

This is because the panel has been taken from a sequence in which Tintin speaks first, so he’s always on the left. If the Captain had been leading, Hergé would have rearranged the layout, while still finding a way to concentrate us on the emotional development between the characters and sneak in the joke about Snowy drinking whisky. Because he was an absolute master at this stuff.

And Flight 714 to Sydney is the work of a master at the height of his powers.

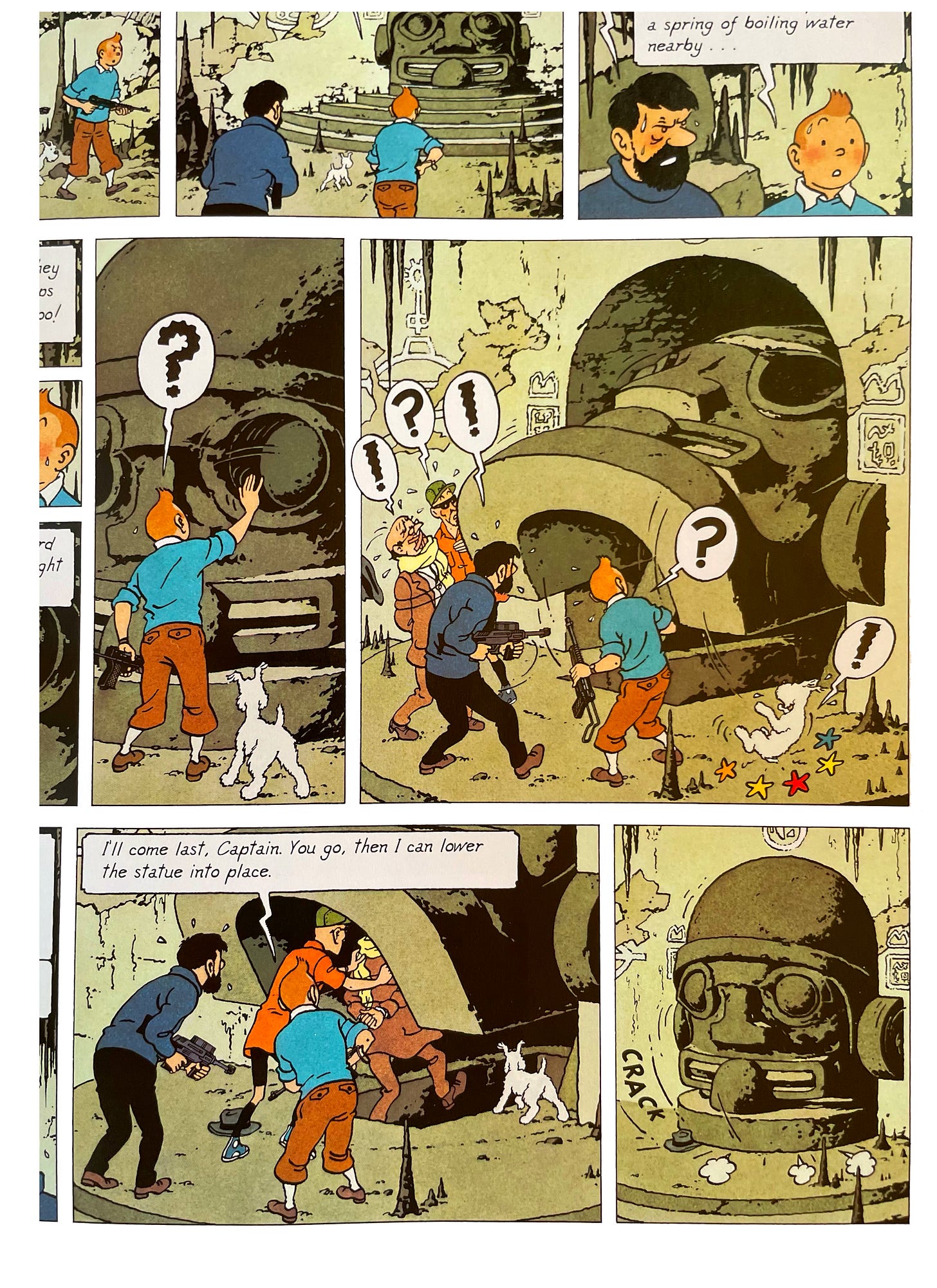

Look at this double page spread. Hergé almost always works in four rows of panels on a large French album sized page. This gives him plenty of space for detail and development.

On the left hand side the panels are chopped up and squeezed up on top of each other to create a breathless intercutting between the characters and the circling place. But he is also giving us a really clear geography, showing us the island and making sure we understand how the plane is moving, left to right from the occupants point of view and then right to left from the ground as it turns, bringing us into the landing at the mini-climax of the page break.

Then on the right the panels expand horizontally but time is squeezed vertically into five rows, each moment frozen and seemingly endless as disaster looms. The characters are forced up against the right hand margin, under the inertia of the big panels to their left. The plane hurtles down the rows of panels in successive incidents: touch down, parachute, failure of the parachute, tyres burst, careening on to the end of the spread. They’re going too fast! Quick, turn the page!

Masterful visual storytelling.

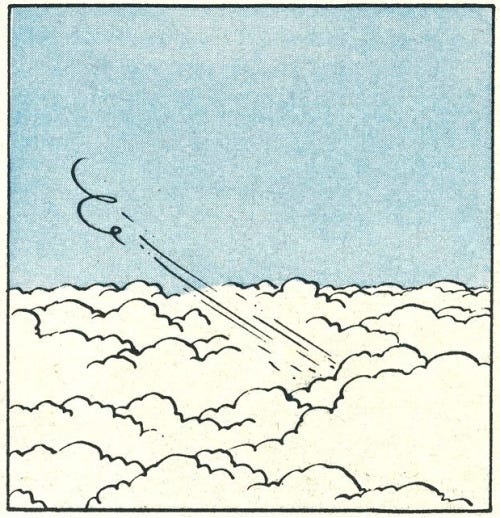

But that’s not all. Probably the real reason Tintin has endured is Hergé’s art style. Someone shared this panel on a tumblr blog the other day and I immediately knew it was Hergé: the colours, the line weight, the distinctive curlicues. It couldn’t be anyone else.

Hergé illustrates in what’s known as a clair ligne style - ‘clear line’. He was fundamentally a black and white artist and always apparently slightly suspicious of colour, so his fundamental tool is the solid black line. Characters, scenery, all of it delineated in a crisp, flowing black outline, making them stand out neatly with a legible graphic clarity.

It seems simple, that solid black line, but it's a deceptive simplicity.

Hergé was an absolutely magnificent draftsman, drawing scenery, buildings and machines with an accurate and exquisite detail. Look at the stone idol above, all the hieroglyphs on the crumbling wall, all drawn with minute attention.

But he was also a terrific cartoonist, capable of visualising emotion in simple poses full of energy. Look at the Captain in that second panel, caught off guard, off balance, bringing his gun up in panic.

And look how the two skills work together, the characterful, vital figures in the fully realised world, foregrounded in it and dramatised by it.

Here Hergé’s suspicion of colour becomes a strength. Those solid, distinctive fills for the characters: Tintin’s bright blue jumper and brown plus fours, the Captain’s ever present dark blue roll neck (with an anchor on the front, naturally), these don’t just give them an instant, iconographic recognisability, they don’t just give them a graphic impact, they’re also astonishingly beautiful.

Hergé’s palette is just wonderful, perfect blue skies, perfect green fields, striking red and yellow trains and planes and automobiles, bright, beautiful clothes, everything precisely the right colour and every colour precisely the most beautiful shade.

Each panel is a little jewel box of sharp lines and shining hues. Hergé’s precision and painstaking framing making each a delightfully detailed little diorama, a little display of mid-century modern; the styles, mores and glamour of a past world carefully, safely preserved inside a book.

This isn’t the first time we’ve covered comics (and it’s bound not to be the last - did you notice that Calvin and Hobbes reference in there?)