Every generation throws a hero up the pop charts, but the Boomers did more than perhaps any other to reinvent popular culture and explode the canon. So what did we, Generation X, make of the things they insisted were hits?

Pre-teen Nigel Molesworth, curse of St Custard’s, introduces parents and prospective pupils to life in a ‘50s British prep school using his own idiosyncratic speling, jaded portraits of boys and teachers, and a lot of obscure references. As any fule kno.

The Legend

Down with Skool has its origins in the meeting of two great British institutions: long-running humour magazine Punch; and the fictional St Trinians School for Girls, famous for the violence and unruliness of its pupils.

St Trinians was created by the writer and artist Ronald Searle as an amusement for some young relatives and quickly became a smash hit, spawning a series of film adaptations. Naturally, Searle tired of it more quickly than his publishers, who carried on demanding more books. When writer Geoffrey Willans approached him with an idea for another school story, Searle was sceptical. But Willans’s ‘Molesworth’ pieces for Punch were so good Searle couldn’t help himself, and everyone had another hit on their hands.

The partnership between Searle and Willans was inspired. Searle doesn’t so much illustrate Molesworth’s ramblings as expand the world around them. There are occasional spot illustrations tied to the text, but most of the time Searle is producing his own visual version of St Custard’s to parallel Willans’ written vision: galleries of masters and pupils; illustrations from imaginary and bizarre textbooks; the weird inventions and flights of fantasy of Molesworth and his chum Peason (‘Acktually he not bad tho we argue a lot saying am not am not am not am etc until we are called on to tuough up a few junior ticks.’) Between them Searle and Willans created a sort of antidote to school stories: a jaundiced view of British institutions for a new Elizabethan Jet Age.

At this juncture it might be worth elucidating a couple of terms. In British English, ‘prep school’ means a school at which one is ‘prepared’ -- generally between the ages of 8 and 12 -- for ‘public school’. Like ‘public schools’, ‘prep schools’ are private and fee-paying. They also often offer ‘boarding’, in which parents pay schools to take their children away and keep them away. Or, as Molesworth puts it:

Being a baby is alright but soon all the boys who hav been wearing peticoats chiz chiz chiz begin to get bigger. they start zooming about like jet fighters climb drane pipes squirt water pistols make aple pie beds set booby traps leave tools about the garden refuse to be polite to visiting aunts run on the flower beds make space rockets out of pop’s golf bag and many other japes and pranks. It is at this time that parents look thortfully at their dear chicks and sa IT IS TIME WE SENT NIGEL TO SKOOL.

That these elite, fee-paying private schools are known as public schools is revealing. The ‘public’ bit comes from the fact that they were often originally founded as charitable institutions, but its retention is indicative of their role in British society. Since Tom Brown’s School Days (1857), the ‘school story’ has largely been a public school story of japes and injustices amid gloomy neo-gothic Victorian piles. It tells us how small boys are made into officers and gentlemen, and how a certain kind of stereotypical Englishness is formed. (Any Scottish or Welsh child sent to a public school is automatically rendered ruling-class English by the process, I’m afraid, despite what they might protest).

Down with Skool and the other Molesworth books make fun of this wilful class structure while revelling in the brutal and shabby reality. It is no coincidence that Down with Skool and William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (1954) were published just one year apart. To anyone who has been to one of these institutions, Lord of the Flies is not so much a fantastical allegory as a plain and accurate account of what goes on among public schoolboys when masters are not around. After the stark horrors of the Second World War, it became harder to maintain the old, comfortable myths about these institutions; when composing his portraits of comedic cruelty, Searle admitted that he drew on his experience as a Japanese prisoner of war.

The fundamental role that the public schools play in British society and imagination meant that a book satirising these ideas could become a massive hit. Indeed, its language and jokes became such a part of the national demotic that Smash Hits magazine -- that great champion of British ‘80s popular culture -- would use a Molesworthian ‘any fule kno’ without thinking twice about it.

The Reality

Down with Skool might seem like tame stuff now, but to its contemporaries it played into a fundamental change in British society after the war. A new, nationalised education system was creating new opportunities for the middle and working classes; coupled with an economic boom, the social orders were upended. The Empire which had -- in fiction at least -- been carved out by all those public school boys dwindled; Britain’s new global cultural dominance was driven by ordinary kids with cameras and typewriters and guitars.

This social revolution was not, of course, total. Of the eighteen British Prime Ministers since the Second World War, five -- over a quarter -- had attended Eton. When we think of one of them in particular, Boris Johnson, it is hard to dismiss thoughts of the perpetually shabby, slipshod and shiftless Nigel Molesworth. Even Clement Atlee, the Prime Minister who did so much to usher in that new post-War social compact, had gone to boarding school. But the cultural role of those schools has changed. Old boys like me are more likely to gloss over the fact that we went to public school; we long ago threw away the school tie, and on our LinkedIn profiles we carefully omit our alma maters.

I first met Nigel Molesworth when I was at prep school. A prep school in the ‘70s wasn’t that different to one in the ‘50s; we learned Latin from teachers who had fought in the War, listened to the radio instead of watching television, wore short trousers, and called teachers ‘beaks’. I understood all of Searle and Willans’ jokes. Forty years later, this has become more unlikely. I suspect few would now get Willans’s joke about Bathsheba (‘Then there was another nasty business about Saul puting a chap in the front line in fact as mum would sa the whole thing is rather like the news of the world’) or the Dan Dare reference (‘You hav caught me, sir, like a treen in a disabled space ship’.) They don’t teach the classics any more.

The social upheavals heralded by Down with Skool have led to its own irrelevance. These days it is part of the idiolect of the class it satirises: a marker of a certain kind of Private Eye-style taste formed in dorms and on cricket pitches, like P. G. Wodehouse and Gilbert and Sullivan.

Is it ok?

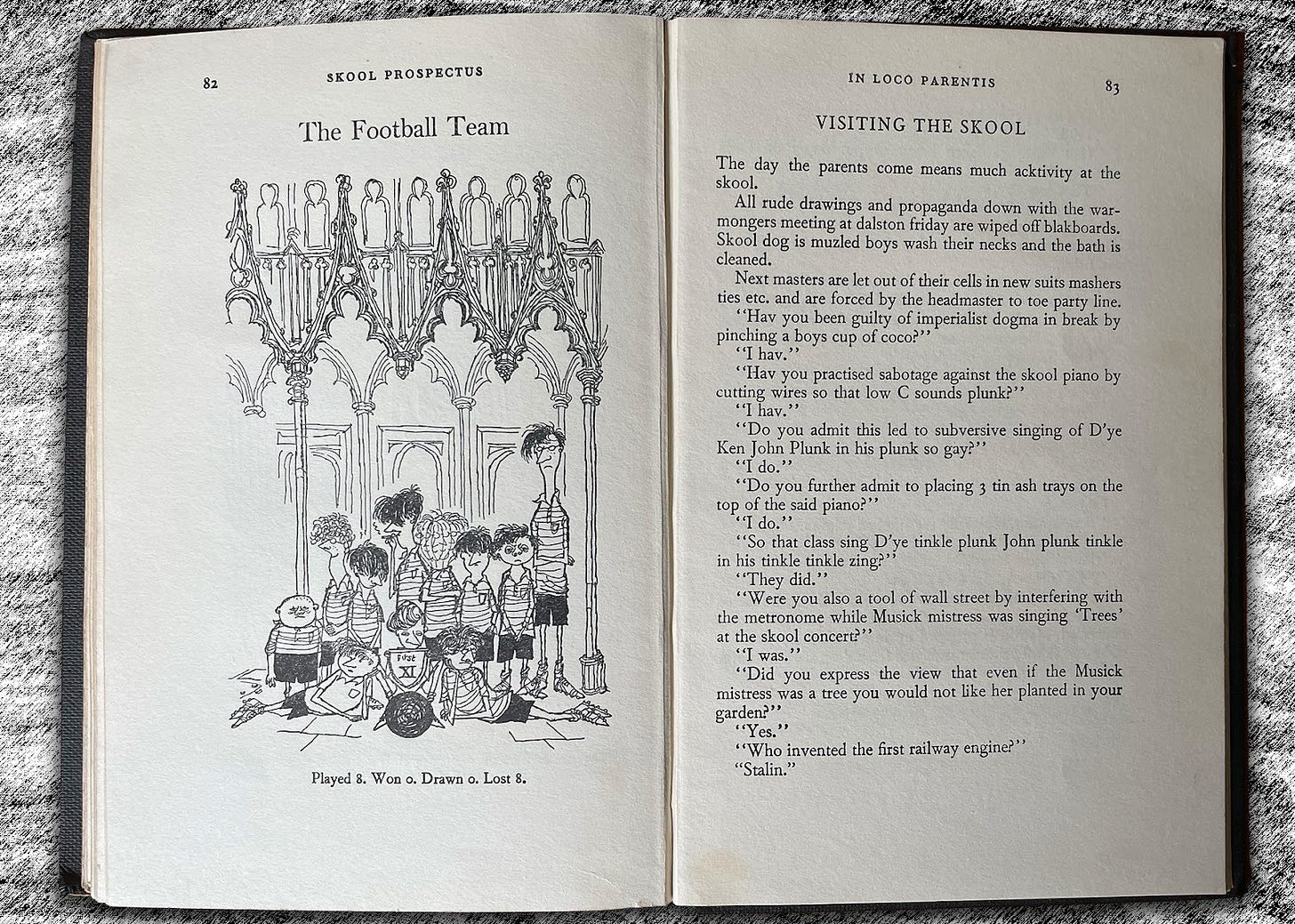

It is worth pointing out that, like P. G. Wodehouse and Gilbert and Sullivan, it is often very good and, more importantly, very funny. In writing this piece I frequently committed the ultimate solecism and read bits out to Rowan because I was so desperate to share them. We both laughed out loud for a solid minute at Searle’s drawing of the football team photograph, and when she sent a picture of it to her 20-something sons, they laughed too.

We laughed at that photograph because we recognised it. Willans and Searle are pulling off a classic satirical move: using a child’s point of view to reveal the accepted realities of the world. There is a lot of satirical mileage in ventriloquising the opinions and observations of one to whom this is all new, and who is straining to understand the world into which they have been peremptorily pushed. This allows Willans to place statements like ‘History started badly and hav been geting steadily worse’ into Nigel’s mouth and have us all recognise it as a universal truth.

Parts of the jokes rest on culturally specific knowledge, but many of them manage to be funny anyway. Look at the joke opposite the football team photograph. The Headmaster is quizzing Masters about their activities:

“Hav you been guilty of imperialist dogma in break by pinching a boys cup of coco?” “I hav.” “Hav you practised sabotage against the skool piano by cutting wires so that low C sounds plunk?” “I hav.” “Do you admit this led to subversive singing of D’ye Ken John Plunk in his plunk so gay?”

Part of the joke requires knowing about Maoist self-criticism sessions; but part rests purely on the fact that ‘D’ye Ken John Plunk in his plunk so gay’ is a delirious sequence of words.

The humour writing that once typified magazines like Punch has largely disappeared; the people who would have been writing it are all running ‘character’ accounts on social media instead. Willans is terrific at it, mixing foolery and satire in equal measure. He is able to both describe the school as having been ‘built by a madman in 1836 and he made a few improvements before he was put in the bin e.g. the observatory to study worms’ and to sum up modern history as ‘the Rise of the People and the People hav gone on rising ever since like yeast until you kno where they are now hapy and prosperus you ask them when the television programme is over.’

And Searle is a genius. Like Willans, his style is peculiarly of its time, mixing a filigree Edwardiana with an inky, jazzy cynicism, a recognisably ‘50s product like the weird contraptions of Rowland Emett or Ealing comedies. However, his art is so accomplished that it creates its own world, asserts its own reality.

Between them, Searle and Willans create a world that, even shorn of its contemporary cultural milieu, is coherent and inviting, a clearly defined setting and cast of characters that becomes its own self-sustaining comic invention. It exceeds its own references to become a reference in its own right. Characters no longer remind us of people; people remind us of the characters. Irritating optimists become Fotherington Thomas; corrupt authority figures become GRIMES the headmaster; crumbing institutions become St Custard’s.

And its legacy, as a place and as a book, continues. In How to be Topp (1954), the sequel to Down with Skool, Nigel -- under the pen name Marcus Plautus Molesworthus -- writes a Latin play. It is called ‘The Hogwarts’. School stories are still very much with us, set in odd and antiquated buildings, peopled by alarming and monstrous figures, and with their own occult and obscure terminology. J. K. Rowling is very much the inheritor of Molesworth’s world, and not just fictionally. Her democratic socialist instincts were set by the post-Second World War Britain that Down with Skool heralded. Her school stories rail against the snobs and bullies who exclude and persecute the hoi polloi1; and yet, like Willans and Searle forty years earlier, she could not resist the ineffable allure of the elite. Chiz, chiz.

Did you know that Adrian Mole was almost called Nigel Mole until Sue Townsend realised who that name reminded her of? Adrian’s a more Gen X name anyway.

Obviously, having had a classical education at a private school, I know the ‘hoi’ in ‘hoi polloi’ is the Greek ‘the’, but having then done an English literature degree I know that being understood is more important than being right and so ‘the hoi polloi’ it is. You wouldn’t want to be a wet swot like Fotherington-Thomas, would you?

The wonderful thing about the Molesworth oeuvre is that it's a rare example of books that have to be read. Most of the jokes are visual - both the illustrations and the speling - so it can't be read to you, and it can't be made into an animation or film, like a comic book.

They're also in that genre of supposedly children's stories that are really for adults - Just William, The Wind In The Willows, Peter Pan, Winnie the Pooh.

I first encountered Nigel in a compendium of school stories I was given as a birthday present in the 80s. The cover illustration was of two very hip 80s teens, but the book was all excerpts from classic literature. I sought out the full length novels from my favourites - What Katy Did, Cider With Rosie, Just William, and Molesworth.

Searle and Willians do capture that era, the decline of the British Empire and the societal structures that went with it, as deftly as Le Carré (but less bleakly). And yes, well-observed that Molesworth-speak is as clubbable as Private Eye, Wodehouse and G&S - all things I also love, despite being a vagina-haver (they tend to be male-coded, by and large).

I have it on my shelf next to 1066 And All That, both guaranteed to make me laugh and laugh. I agree that most of the cultural references are probably illegible to later generations. But… we still get ruled by the likes of Cameron and Johnson and whatever he’s called from the Reactionary Party. And whatever we might hope about history education, history remains “what you can remember”. An awful lot of people think that what happened in history is roughly what was being sent up in 1066 - published in 1930. It was also based on Punch pieces. What was already thought ridiculous then - and Punch was never a radical magazine - is still taken seriously now. And when these people rail against “wrong” or “woke” history, it’s this they want to get back to. But the joke’s on us for letting them get away with it.