Strange how potent cheap music can be. It can preserve a moment, trapped in vinyl; and it can last a lifetime, accompanying, inspiring, supporting. Year by year, these are the songs that have soundtracked our lives.

In 1989 I was working and living in London with my friend Lars, saving up to go on holiday before starting university. By the time we finally went away, Lars and I had filled a whole backpack with home-recorded tapes: our taste, our friends’ tastes, our families’ tastes, other people’s families’ tastes. As we drove across Europe we listened to one after the other on the car stereo. Most of them were thrown into the back seat when we were done.

Two C90 tapes, though, were on heavy rotation. Our friend Ben had made them for us: four sides, four albums. Three of those records were by legendary indie bands. The fourth was something you probably won’t have heard of. (Contrary to the usual hipster implication, this is an indication of your good taste and discretion.)

However, it is in the nature of a cassette that the easiest way to rewind it is to listen to the other side. Every time we listened to one of those albums we listened to the one on the other side too. This means that for every play of Doolittle, we racked up one play of an album that for everyone else had immediately sunk into rightful obscurity.

The lesson of this story is that the music you listen to on repeat when you’re 19 gets burned right in there, whether it’s one of the greatest records ever made or its Beelzebubba by The Dead Milkmen.

Doolittle — Pixies

Can there be a gift any more generous than a copy of Doolittle, the third(ish) album by the Pixies? Especially if, like me, the recipient hasn’t ever heard the Pixies before.

Among its many uses, home taping was a gift to adolescent gifting. A C90 tape was considerably cheaper than two albums; for the price of a pint and some fiddling around with aux leads, you could give a friend two whole albums and spend the leftover money on more beer. Of course, it meant less beer for Black Francis and Kim Deal, but at 19 other people’s copyright is not perhaps the priority it should be. And like all good presents this also allowed the giver to show off their taste a little.

Ben’s gift to Lars and I was the perfect soundtrack for being 19 in 1989 in the greatest city in the world. London was largely shabby and empty in those days; it had not yet recovered from the capital flight of the ‘70s and early ‘80s. There were impromptu weed-filled carparks on bombsites left over from the Blitz; there were empty shop fronts on the Kings Road. But there were also Hooray Henrys everywhere, girls in pearls and twerps in red braces, and a new city of finance rising in the old docklands.

Thatcher was in her tenth year as Prime Minister and was growing increasingly unhinged. It was the year of Hillsborough and the Marchioness disaster; there was growing unrest in the Eastern Bloc, but — as we set off for western Europe — the Berlin Wall had not yet fallen, and protestors had recently been mown down in Tiananmen Square. The times were dark and fierce and full of promise. It was summer, and I was young and on the loose in the big city.

Doolittle captured all of this: the screaming, the lopsided song construction, the big tunes. The ferocious glee of ‘Debaser’, the ecstatic doom of ‘Monkey Gone To Heaven’. Quiet, loud, quiet; a wave of mute elation, a wave of mutilation, disaster and joy. The promise and fear of the future.

Tender Prey — Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds

This underground exchange of music through blank tapes mirrored the underground music scene that it so often propagated. Where, for instance, was I going to hear the newest release by Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds? Not in the music section of the local W H Smith (although I did unexpectedly discover Japan’s Oil On Canvas in there). Not on daytime BBC Radio 1, where the fatuous, superannuated DJs were mostly talking over Jive Bunny.

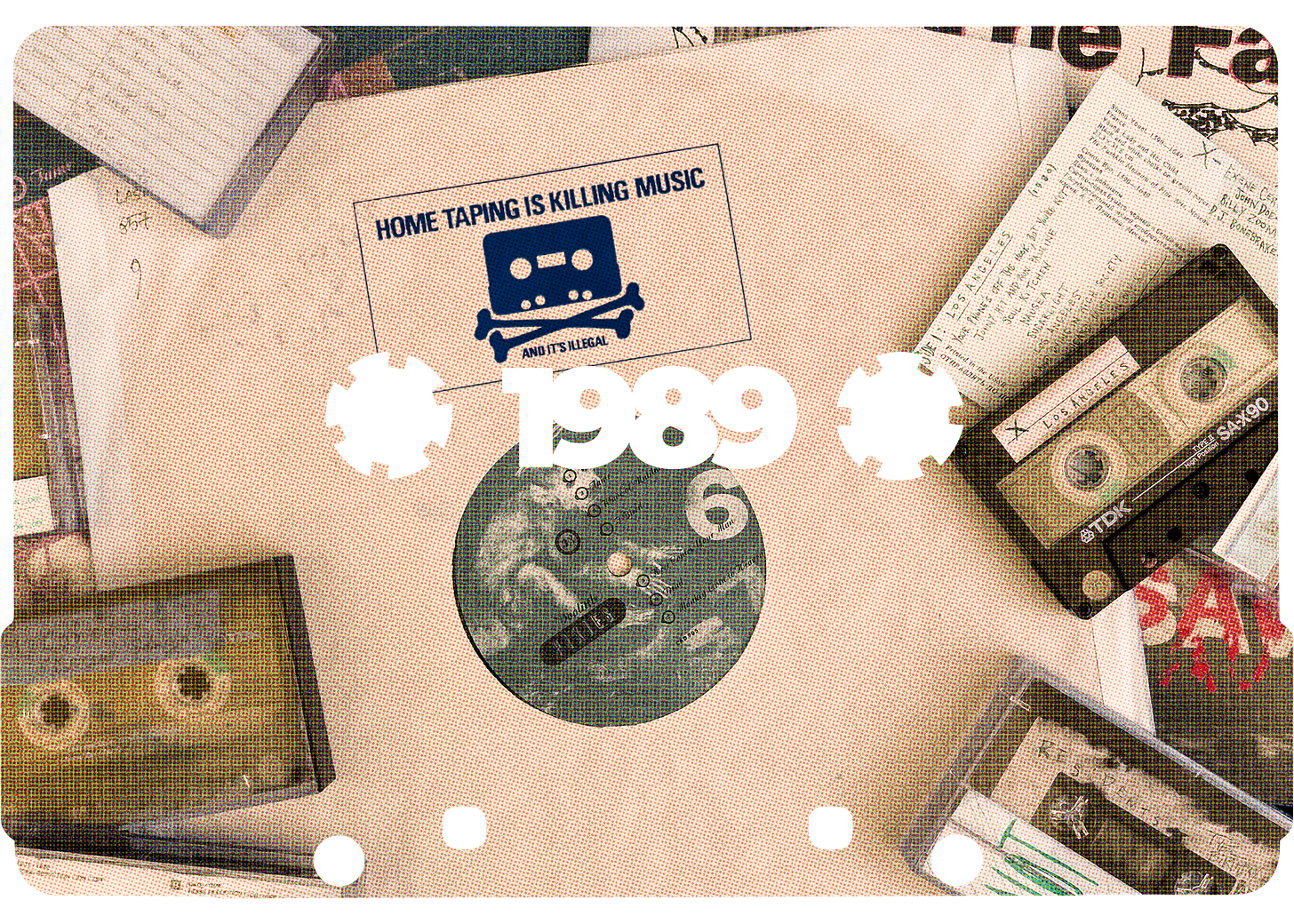

You might hear the new Nick Cave album, though, on a battered Boots-brand blank tape that had been pressed into your hand. Like the music, the tape was contraband, samizdat; a bulletin from the underground. The truly brilliant logo of the ‘Home Taping Is Killing Music’ campaign — a piratical crossbones with a cassette as the skull — only emphasised the rebellious, buccaneering vibe. The homogenised national taste of Radio 1 and Top of The Pops made for a very clearly defined mainstream which, in turn, made for a clearly defined alternative scene, a piratical way of life.

This ease of exchanging music made curation easier and discovery cheaper. It also allowed for a networking of music taste. Your record collection was individual, but your music collection was promiscuously intermingled. Only one member of an extended social group actually needed to own any given record; the rest could all just buy blank tapes and get their own copies. With a little careful planning you could all have a music library that vastly exceeded the scope of your pocket money.

I’d immediately gone out and bought From Her To Eternity (1983) after I’d seen Wim Wenders’ Wings Of Desire (1987), which featured a performance by Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds. But I didn’t own Tender Prey. Ben’s present meant I didn’t have to buy it, and could instead go out and get The Firstborn Is Dead (1985), and through both of these find my way to Elvis and Johnny Cash and Howlin’ Wolf, just as Paul Simon and David Byrne introduced me to African music, and David Sylvian led me to Japanese music.

This Nation’s Saving Grace — The Fall

The stranglehold of the mainstream — four TV channels and two national pop music radio stations — also meant that if someone interesting or innovative got tangled up in it, then they could have a national effect. Someone, say, who really, really liked The Fall.

Cue ‘Pickin the Blues’ by Grinderswitch, which is on none of these records, but (if you’re a British adult of a certain age) will cause goosebumps, a surge of endorphins and possible age-related lachrymosity, because it was the theme tune to the John Peel Show.

John Peel had been part of the founding line-up of DJs for Radio 1, the BBC’s response to the pirate pop radio boom of the ‘60s. He had always championed underground music and that didn’t stop with the arrival of punk. He was our honorary cool uncle, helping to curate and build our taste. I’m pretty sure, for example, that Ben had only heard of The Dead Milkmen because Peel had played them in July 1987; he followed them with Elvis Presley and Sonic Youth, which should give you some idea of what his show was like. You were unlikely to see The Fall on Top Of The Pops, but you were going to hear them on Peel. They were his favourite band, and consequently inescapable.

The glory of a non-commercial, public service broadcaster like the BBC was that the alternative could become nestled within the mainstream, as much as it was defined in opposition to it. A band like The Fall were thus, quite rightly, established as an intrinsic part of the national culture. They are, after all, a quintessentially English band. Or, rather, Anglian. Mercian, even; forever suspicious of the soft South, the Saxons and the Wessex hegemony.

There’s a lot to criticise about Peel, of course, not least his appalling treatment of young women in the ‘60s and ‘70s. But his association with a certain kind of nerdy, male underground music fan is unfair. He himself was constantly infuriated by his fans’ tastes for snotty white boys with fuzzboxes and was determined to make them listen to whatever was new in dub, Zimbabewean rock or techno. Curators can easily become gatekeepers, but they can also be gate-openers, euterpomps, ushering the listener into a whole new perfumed garden of music.

Beelzebubba — The Dead Milkmen

Taste and identity are closely intertwined. The culture we consume inevitably affects our self-image, just as our personal experiences affect our taste. But we also frequently use our taste to identify ourselves.

This can make fandoms extremely deeply felt and closely guarded. They can be exclusive groups. As John Peel said, ‘There are people who don't like The Fall— they must be half-dead with beastliness. I spurn them with my toe.’ He was joking but, of course, he also wasn’t.

As well as a way of defining your own identity, taste becomes a way of sorting others. Perhaps as a side effect of the labyrinthine and underhand discovery process, the indie scene in 1989 was dominated by nerdery. Fans would not accept you if you didn’t have all the right concert bootlegs and Peel sessions, and couldn’t name all members of The Fall. Or, frequently, if you happened to be female. (Of course, not even Mark E Smith could name all the members of The Fall. Neither would he have cared to. As he said: ‘If it's me and your granny on bongos, then it's a Fall gig.’ Although I can’t imagine my grandmother would have had much truck with him.)

1989 was also the year of the infamous NME summit, a meeting in a North London pub between Mark E Smith, Nick Cave and Shane MacGowan of The Pogues, in which Mark E Smith lives up to his reputation as an ornery and self-absorbed troll. Nick Cave emerges heroically, valiantly trying to engage the cantankerous Smith and generously leaping to the defence of MacGowan. This is the flipside of that exclusivity: inclusivity.

This was not just a way of discovering music; it was a way of discovering friends. My party piece at university was a song I had written full of jokes about hillbilly inbreeding, a subject I knew nothing about. I’m not saying it was a good song, but if I found someone else who would laugh at it, then in all likelihood I had found a friend. And so, in a way, any friends I made through this route I owe to the snotty folk-punk of The Dead Milkmen, from whom I was cribbing.

In the only song I still play from this record, ‘Punk Rock Girl’, the lead singer suggests dressing ‘like Minnie Pearl’. This reference, which I had to hunt down, was to a country comedy act who dressed in outmoded ‘40s fashions. Like the music and the jokes, thrift-store chic was a social marker that displayed — like a butterfly’s wings or a baboon’s purple behind — your identity. If you dress like a Nick Cave fan, other Nick Cave fans are going to recognise you, and most likely hand you a C90 containing albums by Swans and A R Kane.1 You, on the other hand, have Einstürzende Neubauten and A C Marias and you can return the favour. All for the price of a blank cassette.

Of course, questions of music taste can be gendered too:

Thanks, Simon

I had a tape recorder with the rewind button broken. To avoid listening to the other side I used to rewind using a pencil and a lot of patience. Turned out to be a great way of contemplating what you had just listened to, and what you were going to listen to again in half an hour or so. You should try one day.

Too hot today for euterpomps