Strange how potent cheap music can be. It can preserve a moment, trapped in vinyl, and it can last a lifetime, accompanying, inspiring, supporting. Year by year, these are the songs that have soundtracked our lives.

Duel

My abiding love for Propaganda’s 1985 single ‘Duel’ is entirely the fault of my school friend Omer. Omer had Belgian connections and a European affect, and he introduced me to all kinds of unspeakable Continental tastes like the film Subway and Swatch watches.

But Omer wasn’t only a fan of Propaganda, a German quasi-industrial electronic band; he was also a fan of their very British record label, ZTT.

Independent and small record labels played an important role in the ‘80s music scene. They had their own distinctive looks and sounds; you would sometimes chance a purchase of an artist you didn’t know if you recognised and liked the label. A 4AD record would have a Vaughan Oliver cover and most likely something shoegazey inside. Mute meant electronica. Rough Trade meant guitars. And ZTT? Well, ZTT promised pretension.

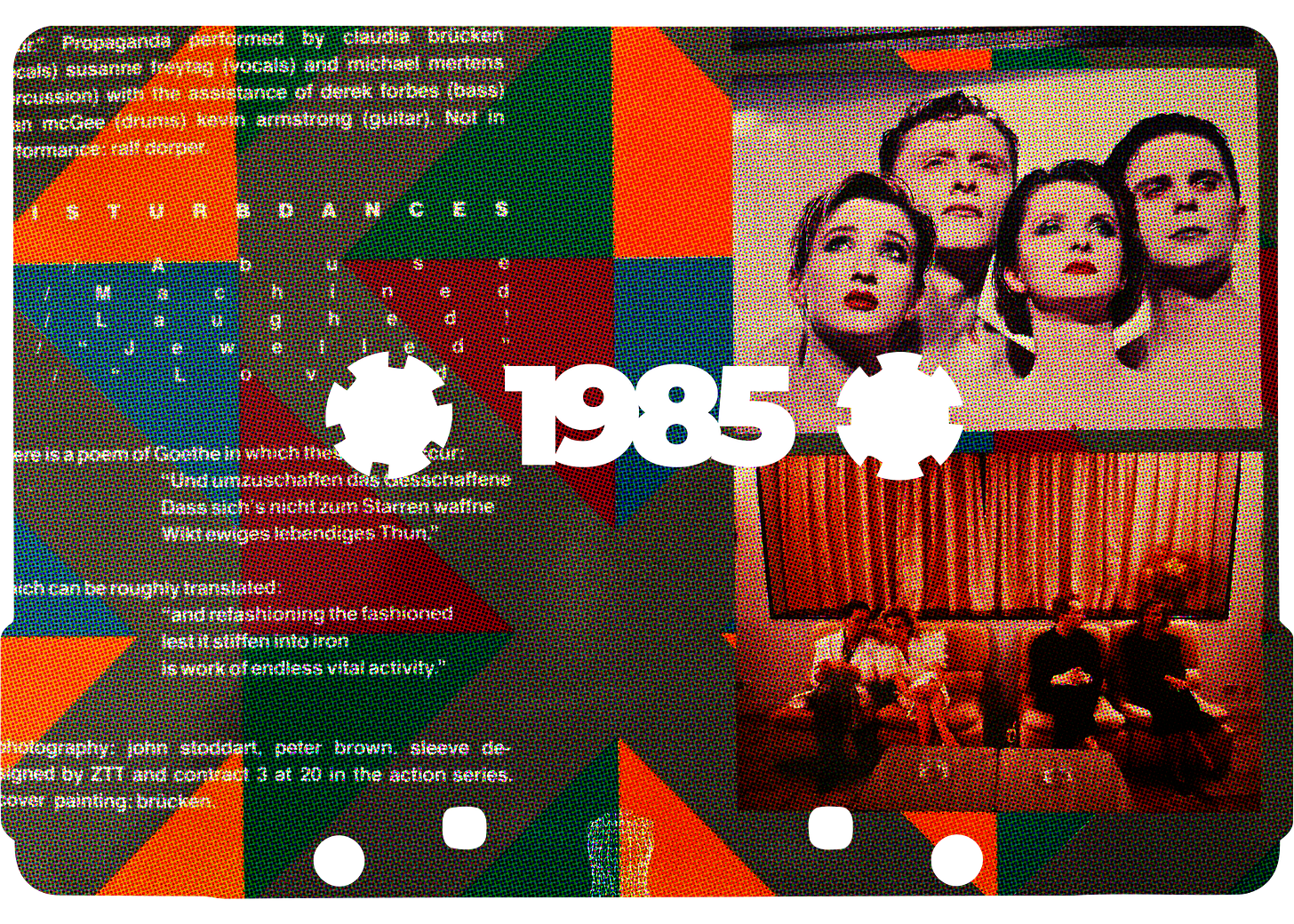

Even the name ‘ZTT’ is pretentious; it comes from a poem by the Italian Futurist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, in which the sound of a machine gun is phoneticised as ‘zang tumb tumb’. (Incidentally, Marinetti once fought a duel with a critic, largely for the swank of it. He was pretty pretentious himself.) The Propaganda record I have in front of me goes so far as to have a quote from Goethe on the back:

Und umzuschaffen das Geschaffne,

Damit sich's nicht zum Starren waffne,

Wirkt ewiges, lebendiges Tun.

ZTT was founded by three people: Jill Sinclair, who co-founded London’s Sarm Studios; her husband, the producer Trevor Horn; and the music journalist Paul Morley. It seems fair to assume that most of the pretentiousness came from Morley; he has enough of it to spare. He was born in Surrey but grew up in Lancashire and went to grammar school there, as did Horn (and their fellow pop/art provocateur and co-founder of Factory Records, Tony Wilson).

It is tempting to see their pretentiousness as a product of this background: that these ambitious, clever and slightly chippy northern grammar school boys enjoyed surprising the flabby, cosy southern public school establishment with their intelligence and sophistication. But it could also be part of the post-punk rising of the North (of England), the way that local scenes in Manchester, Liverpool and Sheffield stood against the mainstream music industry in London while constantly feeding it with novelty and revolution.

Then again, the pretentiousness might have been a challenge to the earnestness of punk and the earthiness of ‘70s rock; an iteration of the New Romantic ‘revolt into style’, a languid middle finger to bands who smelled of pub carpets and knew the price of rolling tobacco. New Romantics had never been afraid of quoting a German poet or two. Propaganda, a band from Düsseldorf, took aim at kneejerk little-Englander anti-intellectualism. (Does any country other than England have an equivalent for the insult ‘too clever by half’? No one is accused of being ‘too agile by half’ or ‘too good a plumber by half’.) When I was a teenager ‘pretentious’ was a common insult, and when I was around it was frequently aimed at me. It felt like a scarlet letter pinned on anyone with a book of translated stories in one pocket and a notebook of poor poetry in the other. It was a switching cane aimed at tall poppies, a curb on the curious.

A record cover with a Goethe quote on felt like a challenge raised on behalf of all the awkward teenage poetasters; a promise that there was another country, somewhere one might be able to discuss books, enjoy paintings, and listen to art pop, all without being insulted. Possibly just on the other side of the Channel, where they made stylish movies and mass-produced designer watches.

Jewel

That Goethe quote above is not on the cover of Propaganda’s first LP, A Secret Wish. Instead, it is on the back of Wishful Thinking, an album of — wait for it — ‘disturbdances’: that is, remixes of tracks from A Secret Wish. In the sort of glorious bathetic mode that so typifies proper pretension, Goethe’s lines are deployed as a metaphor for pop remixes:

And refashioning the fashioned

Lest it stiffen into iron

Is work of endless vital activity

‘Duel’ did not stand on its own. There was always also the B-side, ‘Jewel’, a much more industrial version sung by a different member of the band (Susanne Freytag rather than Claudia Brücken). ZTT was an inveterate releaser of remixes, producing an endless and confusing slew of 12-inches, cassingles (which they popularised) and compilations.

Studio-finessed electronic tracks such as ‘Duel’ lent themselves to this kind of disassembly and reimagining. Jill Sinclair’s Sarm Studios was the first 48-track recording studio in England. It used analogue technology, but prefigured the digital copying and pasting of stems and tracks, the remastering and mashing up.

This is music that never quite settles; it is a continually evolving conversation between artists, audiences and curators. You might see it as a return to a more traditional form. Before recording — the act of setting a particular performance in stone — music was a matter of interpretation and invention.

ZTT’s branding and packaging, though, suggested yet another lens: remixing as the reformulation of a mass produced object, responsive to changing consumer tastes. ZTT were extraordinarily good at branding. Their signature graphics — lowercase sans serif fonts, plenty of white space, primary colours and juxtaposed patterns — recalled the seminal Memphis design palette that Swatch referenced too.

ZTT were responsible for the most emblematic of all ‘80s branding exercises: the ‘Frankie say’ t-shirt. Frankie Goes To Hollywood were ZTT’s breakout act, and as marketing for the single ‘Relax’ the label produced plain white t-shirts with huge slogans in black block Impact font: ‘FRANKIE SAY RELAX DON’T DO IT’, ‘FRANKIE SAY WAR! HIDE YOURSELF’, ‘FRANKIE SAY ARM THE UNEMPLOYED’. Inspired by Katherine Hamnett, these shirts were huge in both size and sales figures, in some shops outselling the actual single they were marketing. (The plural form of the verb — ‘Frankie say’ not ‘Frankie says’ — was arguably correct when ‘Frankie’ is a group of people; but it sounded odd on the ear, because we are used to assuming that somebody called ‘Frankie’ is a single person. This — both the formal correctness and the jarring quality — was undoubtedly intentional, and an absolute chef’s-kiss of pretentiousness.)

But – and this is the crucial thing – as well as being very good at branding, ZTT were very good at making pop records. ‘Relax’ reached Number One in the UK and stayed in the charts for a whole year. ‘Duel’ reached 21 in the charts, which wasn’t bad for a post-industrial electronica outfit from Düsseldorf.

For all the design and posing going on around it, ‘Duel’ is, ultimately, a pristine bit of ‘80s pop. From the opening plangent riff, through the throbbing, nightclub verse (with Stewart Copeland of The Police providing the drum track) to the rising, glorious chorus; from Claudia Brücken’s fog-horn voice wailing over the icy sheets of synthesiser to the great, sliding glacial roars and stabs; it is, to put it mildly, a banger.

This is not music for a poetry reading or a first night opening. This is music for playing loud, for losing yourself in, for dancing. The German poetry, complementary-coloured halftone patterns and endless repackaging were nothing but rococo decoration, a period setting for a shining jewel.

On the front cover of Wishful Thinking is the motto: ‘for the footsteps and heartbeats of the connoisseur’. It sounds pretentious but you know what? They’re not wrong.

For more suspect Continental music, there’s always our piece on French laser harpist Jean-Michel Jarre: