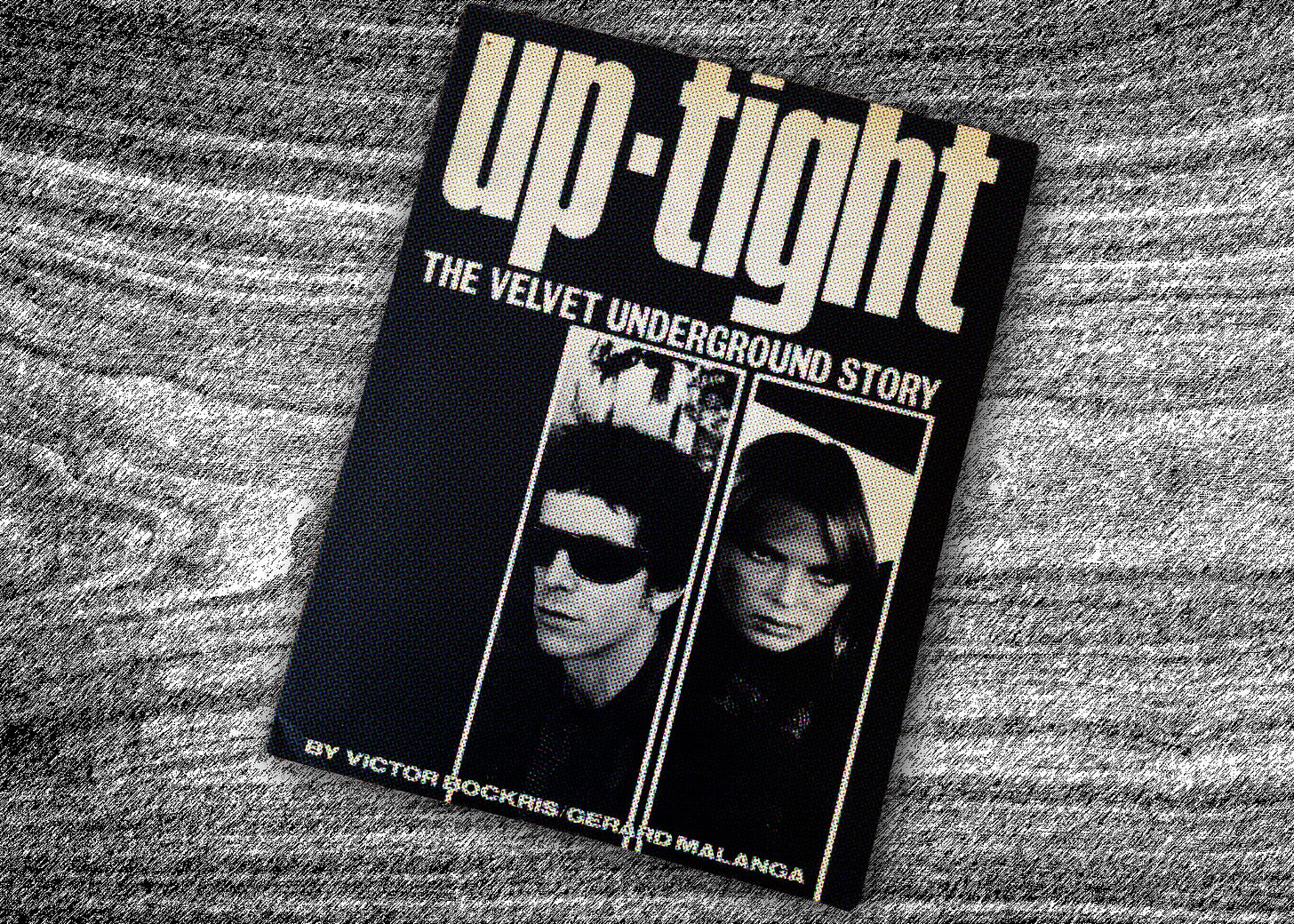

Uptight: The Velvet Underground Story

Victor Bockris and Gerard Malanga (Omnibus Press, 1983)

We were raised by Puffins. With three TV channels and no internet, for long stretches of our lives reading was the best (and sometimes, the only) way to pass the time. Here we return to the books that made us and analyse what makes them great.

Preface

An oral history of one of the most influential bands of all time, from their formation to their relationship with Andy Warhol to everything grinding to a halt as the amphetamines wore off. Given the impossibility of describing the music, expressive dancing, light show and polygonal affairs everyone was having with everyone else, the book largely concentrates on mixing interviews, quotes and diary entries with a lot of photography.

At some point in the mid-’80s, I walked into a friend’s bedroom and into a wall of noise. There was guitar feedback squealing, leaden drums thumping helter-skelter, bass and rhythm guitars grinding and over the top of it all a tired, acerbic voice speak-singing: “I heard her call my name”.

It’s hard to believe that the first time I heard The Velvet Underground I knew nothing about them. After all, no less a person than David Bowie called them more influential than The Beatles. They are the wellspring of pretty much all alternative rock music. But this is how things were in the early ‘80s. If something wasn’t mainstream popular, you simply weren’t going to hear about it. Smash Hits wasn’t going to print the lyrics to ‘Heroin’; even John Peel was only ever going to play contemporary indie music. An art school pop star might namecheck The Velvets alongside Roxy Music and Captain Beefheart in an interview, but you’d never get any sense of who they might be, or what they might sound like. Or even when they might have been recording.

The cover art of their first record included the name ‘Andy Warhol’, which I vaguely associated with the ‘60s, and the photographs on the back looked like some hippyish freak-out, but the music didn’t sound like Pink Floyd or The Rolling Stones. I couldn’t tell whether this was music from that week or twenty years before.

This is what the world was like. You could stumble upon cultural artefacts and not have any context for them: a late-night movie on TV, a paperback with an interesting cover in a spinner rack, a record in a discount bin. If they weren’t already popular or canonised, you could find it extremely hard to discover any more about them. They would exist as a singular, unrelated cultural object, unexplained and unmoored.

On the other hand, this meant they were yours, and your relationship with them was yours alone. I didn’t know that knowing about and venerating the Velvets was a prerequisite for being hip; I didn’t know that a whole lineage of alternative rock music descended from them. I just knew that they sounded unlike anything else I had ever heard, and in response my mind split open.

Contents

Serendipitously, and somewhat inexplicably, the school library had a copy of Uptight, a history of The Velvet Underground. It enabled me to put names to sounds: Lou Reed, John Cale, Maureen Tucker and Sterling Morrison, as well as Andy Warhol and the mononymous Nico. I could also put faces to scenes: the happenings and situations and movies and gigs. And I could put a ‘why’ to the ‘what’: Pop Art and Minimalist music and the underground movements of the mid-‘60s.

Finally, I had some context. This both diminished the music and enhanced it. I understood where it sat in the history of rock n’ roll: what it was influenced by, and what it influenced. It was no longer that sui generis marvel that belonged to me and me alone. But, on the other hand, whole new slices of culture were opened to me.

There was an underground to the underground. I had been raised on the legend that the Boomer generation had reinvented popular culture into a psychedelic revolution in the head, between the sheets and on the streets. Now, I learned there had been a revolution against that revolution: a parallel ‘60s that found peace-and-love, Haight Ashbury hippydom as boring as the ’80s post-punks did. As Velvets guitarist Sterling Morrison put it in the book, New York was the best place to be in the Summer of Love, because the Summer of Love entirely passed it by. Every flower child and ‘teenage ninny’, ‘every creep, every degenerate, every hustler, booster, and ripoff artist, every wasted weirdo’, packed up and left for San Francisco, leaving Manhattan a quiet and peaceful playground for Andy Warhol and his cohorts.

This sort of thing was absolute catnip to a Gen X teenager, not to mention that they all looked so extraordinarily cool in the photographs. All in black in Warhol’s silver Factory, motorcycle boots, strange jewellery and sunglasses after dark. It was a look that was quite at odds with the ‘60s stereotype of floating Kaftans and scraggly beards.

Then there was that fundamental attitude that gave the book its name. ‘Uptight’ meaning anxious, tense, angry, paranoid; this was the anti-hippy sensation that Warhol was trying to induce with ‘the Exploding Plastic Inevitable’, the multimedia experience that accompanied Velvet Underground gigs. Another word for this sensation is adolescence: being at odds with the world, and oneself, and especially with all those Boomer adults who kept banging on about the ‘60s. A ‘60s that, it turned out, hadn’t been at all what the mainstream claimed.

Afterword

This book is about so much more than the Velvets. At one point Lou Reed lists all the bands he adored in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, enough material for a whole lifetime of bin-diving in record stores. And that’s just the start of the references: Frederico Fellini, William Burroughs, Allen Ginsburg; The Fugs, The MC5, The Stooges. Even the indicia contains clues: the book was laid out by Neville Brody, the designer responsible for reinventing magazine design with The Face.

You discovered context for one object and in return, like some shady deal with a storybook fairy, you were given a clutch of new mysteries, a bundle of new threads to follow through the cultural labyrinths; names to note down and remember for the next time you were in a second-hand book shop or record store. These were hyperlinks that took months to click. Sometimes they led to dead ends; sometimes they led to mind-blowing discoveries.

We’ve written before about the significance of Gen X’s cultural curators; the people – like Victor Bockris – who pulled together these webs of reference, bringing treasure and the starting points for new hunts. These hunts weren’t only for new authors or bands; sometimes they led to new friends, people who had made some of the same discoveries as you but who had also taken their own paths through the cultural wood. You had John Cale’s album Fear, but they had Nico’s Marble Index. They had Ginsburg’s Howl, but you had The Naked Lunch.

Now, of course, we can just click ‘About the artist’ in Spotify and start Googling the names we find there, spelunking the Wikipedia entries for obscure bands and watching the YouTube videos about them. We crave curation; paradoxically, with the world at our literal fingertips we need it even more. We need that advice about what’s worth seeking out, and where we might find hidden gems.

Anyone can find and listen to The Velvet Underground now, but we still need Victor Bokrises to make sure that people do, and have their minds blown all over again.

For more stories about friends passing on bands and changing lives, try Chris Waywell’s piece on Beck

So true that last bit about curation. I have only recently stumbled across "Peel slowly and see", been playing it since. Especially the demo versions. And I haven't come anywhere close to the bottom of it yet. I wish some curator had told me before.... so many years wasted, again!

The ways we stumbled onto cultural artefacts were truly random. I traveled to Paris with my family in 1990 when there happened to be an Andy Warhol retrospective on display at the Centre Pompidou. I somehow picked up some tidbit of information about the Velvet Underground, probably from the signs or the pamphlet that accompanied that show. Maybe I saw a photo. I remember my dad being amused that I was so intrigued by this band, which he knew plenty about, but he told me to my dismay that he had sold or traded his copy of the peeling-banana record long ago. I ordered a copy of the cassette from our local record store when I got home and fell in love. I must have put "Femme Fatale" on a hundred different mix tapes in the years that followed. I did the same thing when I read Kurt Cobain name-drop The Vaselines in a Rolling Stone interview, and quickly got my hands on one of their albums. Like little passkeys into coolness.