Uneasy listening

The lounge music fad in '90s London

At one point in the early ‘90s a friend and I were turned away from a Soho pub for wearing suits. Suits were for management stiffs or trouble-making wideboys, coked up ad execs in Armani or drunk-fighting estate agents in unfortunate shoes and something shiny off a peg at Next. Pubs, especially pubs in fashionable Soho, didn’t want that kind of clientele.

We were not, needless to say, coked-up (we couldn’t afford it) or fighting drunk (how could we be, they wouldn’t let us in), nor were we in Armani or Top Man. I was wearing a three-button, single breasted ‘60s suit and a loud ‘50s vintage tie, and my friend had made his suit himself. We were worse than estate agents and advertising people: we were hipsters. And we were fans of easy listening music.

The standing joke about John Major, the Prime Minister at the time, was that he ran away from the circus to join a bank. It wasn’t strictly true. Tom Major, his father, wasn’t in the circus; he was a vaudeville man (and possibly the inspiration for fellow Brixton boy David Bowie’s Major Tom). By the time John was born, Tom was running a business selling garden ornaments.

But the sentiment holds true. Teenagers rebel against their parents, so if their parents are weirdos, the children end up straights. If your parents are Baby Boomers - the generation that defined teenage rebellion, refined rock n’roll and designed pop culture - what else could you rebel into but easy listening?

Easy listening was the music Boomers had rebelled against in the first place: the music of the Greatest Generation, big band swing and cafe jazz, the mainstream ‘50s and ‘60s. The sinister exotica of the tiki lounge, plangent country guitars, the melancholy syrup of ‘60s pop strings.

More immediately, my friend and I were also rebelling against the pop culture of the late ‘80s. We stood against the hyper-designed black ash and primary-coloured polyurethane Studio Line slickness, and the pilled up, blissed out street style of the Second Summer of Love ravers. Raiding charity shops for vintage clothes, we also found the sort of Martin Denny and Dean Martin records that would so splendidly appal the creaking rock dinosaurs clogging up the charts with their wheezing approximations of pop.

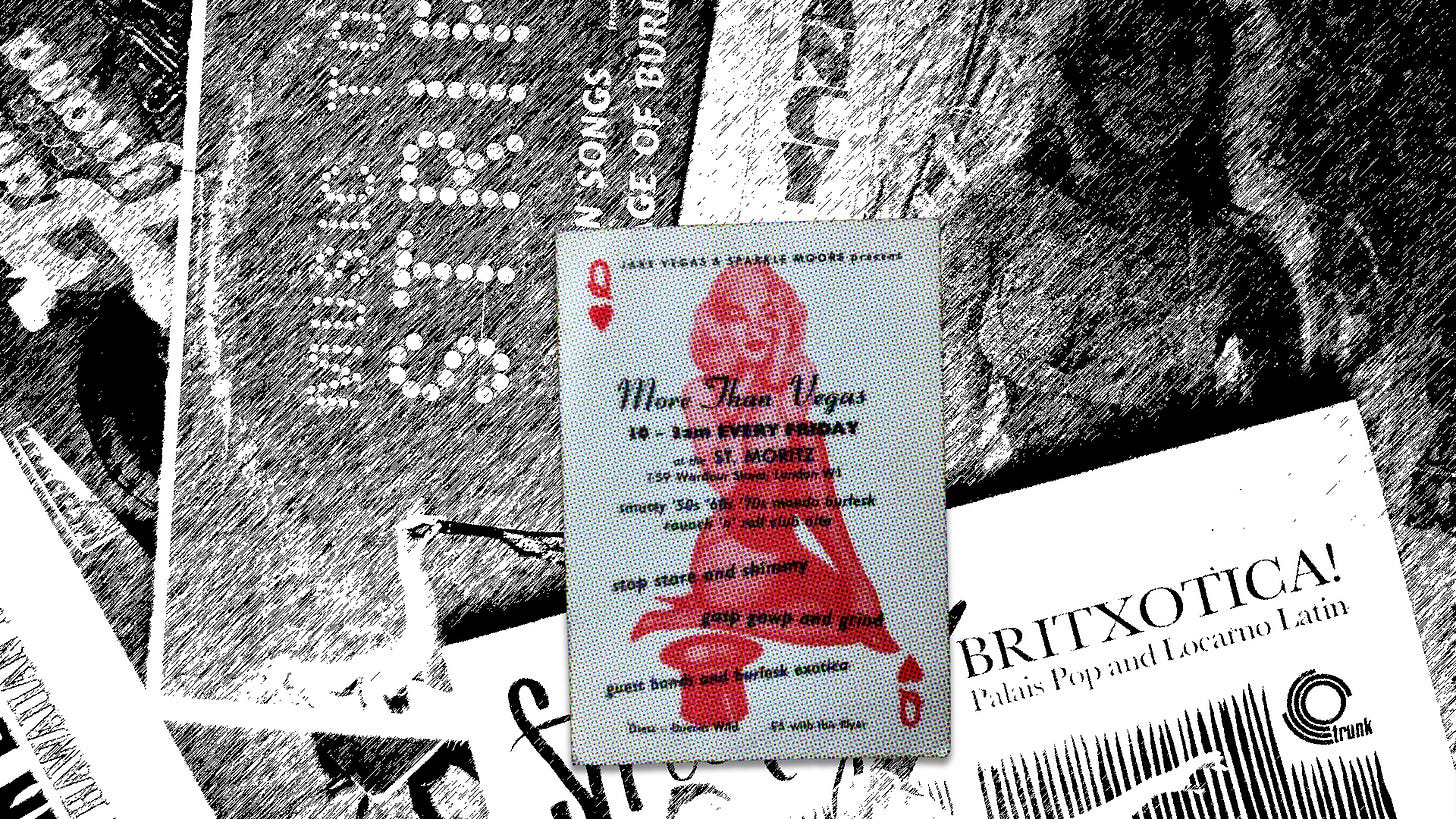

We were affectedly outsider, determinedly antagonist to the mainstream, carefully weird: we were hipsters. Early ‘90s London seemed full of people buying old music library records by composers like Alan Hawkshaw and Keith Mansfield. There were swinging ‘60s nights at places like Soho’s St Moritz club and Nancy Sinatra on the jukebox at Britpop central, The Good Mixer pub in Camden, an influence that could be heard later in hits by Belle and Sebastian and The Divine Comedy.

Like all hipster behaviour, ours was profoundly bourgeois. As well as the defiant oddness and self-congratulatory exclusion, what makes hipsters objectionable is that they have a middle class assuredness and, more importantly, the money that buys that confidence. Their fashions are the poses of the possessed, and so profoundly irritating.

But then easy listening is a bourgeois genre, which again is why so many people dislike it. It is comforting music for the comfortable, the background to dinner with the bank manager and fondue in the conversation pit. Unthreatening sounds for unthreatening people. Unthinking, unnoticed.

However, like many supposedly unthinking cultural products, easy listening records contain unexpected and unexamined depths. As in the weird pall of Tretchikoff’s Green Lady, or the queasy gothic of Margaret Keane’s big eyed children, popular art is often unnerving. The unguessed at unconscious stirs beneath the bland surface, like a large shape turning in dark water. With a strain, also, of the quietly mad.

Martin Denny’s sinister Enchanted Sea is an eerie siren’s call through sea mist, suddenly punctuated by a band member doing a terrible impression of a seagull; a ludicrous interjection into the uncanny scene. Geoff and Maria Muldaurs’ version of Brazil has all the jaunty syncopation of a ghost story calliope, becoming increasingly unhinged as it goes on, the sound of a haunted merry-go-round in a long abandoned funfair.

These hideously normal artefacts are actually deeply weird, revealing the unspoken truths about the suburbia to which they were the soundtrack: the casual misogyny of Dean Martin, the anguished masculinity of Frank Sinatra, the stifling boredom of Mantovani. That strangeness, that distance, that absurdity was part of the appeal. If the early ‘90s liked anything at all, it was not liking things. Or at least only liking them ironically, maintaining a knowing remove.

Taking things too seriously could take you to uncomfortable places. You could end up like Vince Vaughan’s grating, sexist twerp in Jon Favreau’s 1996 film Swingers, who has taken Dean Martin’s stage act as a direct model and, in consequence, is a doubtful human being. Favreau’s character is almost as irritating, all Woody Allen New York nebbish ticks and nice-guy ineptitude, but at least he finally realises that the Rat Pack lifestyle they all emulate is an unpleasant dead end; that he is, eventually, going to have to stop playing at being a playboy and act like an adult. An adult actor, but still.

What’s revelatory is that he comes to that revelation through the music. Through, specifically, dancing with Heather Graham to swing. Swing dancing encapsulates a lot of the appeal of that ‘50s style. Not just tailored clothes and tightly orchestrated big bands, but also the need to rehearse, to practice, with another person. Dancing, coordinating with a partner: an astonishing alternative to the self-expression of the nightclub.

It is in this physical contact, this interaction, this commitment to each other’s enjoyment, that Jon Favreau’s Mike rediscovers the promise of adult romance. That apparently ‘adult’ veneer of the post-war world is a good deal of the appeal of the genre. As a generation raised by Boomers who refused (are still refusing) to grow up, whose watchword was to never trust anyone over 30 even as they advanced into middle-age, Generation X found the maturity of their grandparents’ world fascinating. Graduating into an economic nightmare, we looked back fondly on what was portrayed as a time - particularly in suburban America - of predictability and comfort. Swingers makes great play of this, contrasting the mid-century affectations of the characters against their shoddy, incomplete ‘90s lives. Their use of ‘money’ as the ultimate term of approbation hints at a fundamental shallowness and precarity at odds with their attempted image.

At least the ‘90s world of the Swingers is more evolved than the one they idolise. They can go to bars with their Black friends; the women they meet, despite the best efforts of the immature protagonists, have agency. The ‘50s and early ‘60s were a time of prosperity and comfort only for some; the Boomers didn’t rebel against nothing. In 1996 fantasy Pleasantville, ‘90s teenagers Tobey Maguire and Reese Witherspoon get sucked into the sterile world of a ‘50s TV show, and discover there all the oppression and repression of the period. It’s not the subtlest of movies - the ‘50s fantasy world is in black and white, but as they become socially liberated the characters burst into technicolour, becoming *ahem* ‘coloureds’, who are then discriminated against - but it’s also not wrong.

There’s a reason that Miloš Forman chose Mantovani as the ambiance of the hospital in One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest, the soundtrack to the ruthless rule of Nurse Ratched. This was the syrupy sound of oppression, the music of the relentless mainstream. The reason the Boomers couldn’t stand it is because it was what they rebelled against in their time, the world they overturned, and certainly in sex, sexuality and race equality, for the better.

Maintaining an ironic distance was, then, vital, to maintaining enjoyment without having to consider the political implications. But, as ever, the Generation X ironic stance hid a deeper sincerity. Because what we craved, really, was precisely that: sincerity. A break from the ironic detachment and arch playfulness. Something of feeling, something of emotion.

There is a moment in the 1997 spy-spoof Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery when Mike Myers opens a bottle of champagne, breaks the fourth wall and says, with a genuine sincerity and affection: “Ladies and Gentleman, Mr Burt Bacharach”.

And there on the open top of a Britpop-Union-Jack-painted double decker, riding through Rat Pack Vegas, Burt Bacharach sings the opening to “What The World Needs Now”. For a moment, just as Swingers becomes serious about swing dance, the movie stops being jokes and just enjoys the glorious romance of the music. Only a moment - there’s immediately a comedy sight-seeing montage - but it's there. Sincerity. No one does sincerity quite as splendidly as Bacharach and David. The glorious drama of Dusty singing ‘Anyone Who Had A Heart’, the gentle yearning of Dionne Warwick’s ‘Do You Know The Way To San Jose’, even the ludicrous cheerfulness of ‘Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head’; all of them are deeply meant and earnestly delivered, to perfect effect.

This sincerity is precisely why it is so derided and precisely why it is so delightful, because of what it is being so sincere about: mundanity. Where most pop music is full of the great emotion and excessive drama of adolescence, easy listening is the music of adult resignation, the true sound of the suburbs. It is the muzak in the supermarket, the low fuzz of the radio in the greenhouse, the sussuration of a thousand car stereos in a tailback. It is the slow rhythm of the daily grind, commute and schoolrun, shops and back home for tea.

But for me at least, this is the secret delight of easy listening. The tunes are whistleable, the orchestration can be hilarious, but underneath there is an abiding strain of a sincere melancholy. An earnest, adult realism. A life a little thwarted, not quite fulfilled; a suburban life, constrained, mundane and full of dreams. All adult lives, in some way or another, most of the time. And nothing catches this as well as that late ‘50s, early ‘60s middle-of-the-road pop. A swinging beat, plangent horns and a quiet summer’s afternoon. Lee Hazlewood and Nancy Sinatra. Sweet and sour and glorious.

And I’m being sincere about that.

I got some troubles, but they won't last

I'm gonna lay right down here in the grass

And pretty soon all my troubles will pass

'Cause I'm in shoo-shoo-shoo, shoo-shoo-shoo

Shoo-shoo, shoo-shoo, shoo-shoo Sugar Town

For more dubious music tastes:

Loved this, and couldn't help but hear Spoon's "The Fitted Shirt" in my head while reading it.

Another reason to add to the pile you've already listed re: appreciating mediocre malaise is that sometimes the reason people feel compelled to rebel against the mainstream, to "follow their dreams," to shake the dust of <insert normal thing here> off their feet, is that they've simply had it too good. Having never felt true war/terror and never lived on the knife's edge of survival, they have to fabricate terror for themselves. For a lot of people who have grown up under rough circumstances, and a lot of immigrants who've had to struggle, plain old boring middle class life where odd home improvement projects are your biggest worry is a luxury. This is why the current siren's song of "Quit your regular job and follow your dreams and open up that crystal and tarot reading shop!" doesn't work on me. I think I'm like...*just* self-aware enough to know that this regular middle-class life IS a great many people's ultimate dream. And I feel grateful to be annoyed about the small things I'm annoyed about on a daily basis.

And lest I take myself too seriously, also filed tangentially to all of this in my head (albeit with less sincerity and more camp): Depeche Mode's video for "It's No Good."

Lovely bit of writing!