Friends

Another Country and the emotional appeal of male friendship

I didn’t know many boys in 1984. I was at an all-girls school, so that was no use, and my extended family - which included the usual proportion of boys - was 200 miles away in Wales. At the weekends my dad coached the boys’ under-15s rugby team at London Welsh, which brought him into regular contact with the then-Labour leader Neil Kinnock whose son Steven was on the team. This situation should have been rich pickings, but speaking to these boys - strong, beautiful and constantly jogging in a pack of 20 - was flatly impossible. One evening at a club fundraiser disco, wearing an outsized bow in my hair (to this day I curse that bow and whatever cerebral event caused my mother to buy it), I spent a painful half hour watching Neil’s daughter Rachel circulating effortlessly with Steven’s team mates. I realise now she’d been watching her parents gladhand since the day she was born, but at the time her social poise and ease of manner in a crowd of young men simply looked like a wretchedly unfair form of witchcraft. Just when I thought things couldn’t get much worse, Neil visibly took pity on me and dad-danced me around the floor to the Ghostbusters theme song. He was punching the air during the chorus.

So, as far as relationships with male people went, I had my dad and my brother. (Also, I suppose, Neil Kinnock.) Neither my dad nor my brother brought their friends home very often, possibly because there was a weird thirteen year old girl there. My brother was at St Paul’s School in Barnes and most of his friends seemed extraordinarily unpleasant, although that didn’t stop me being interested; I was at a comprehensive, and the ways of my brother’s public school - Latin, 13 O Levels, Common Entrance, ‘prep’, really quite stunning levels of physical abuse - were intriguing to me. So when my friend Lizzie said she’d seen a film called Another Country and it was about public schoolboys and the actors in it were absolutely gorgeous, I was fully primed. The next Saturday afternoon we headed to her house in Twickenham for a sweaty appointment with her VCR machine.

Something was set in train that day from which I’m not sure I’ve ever recovered.

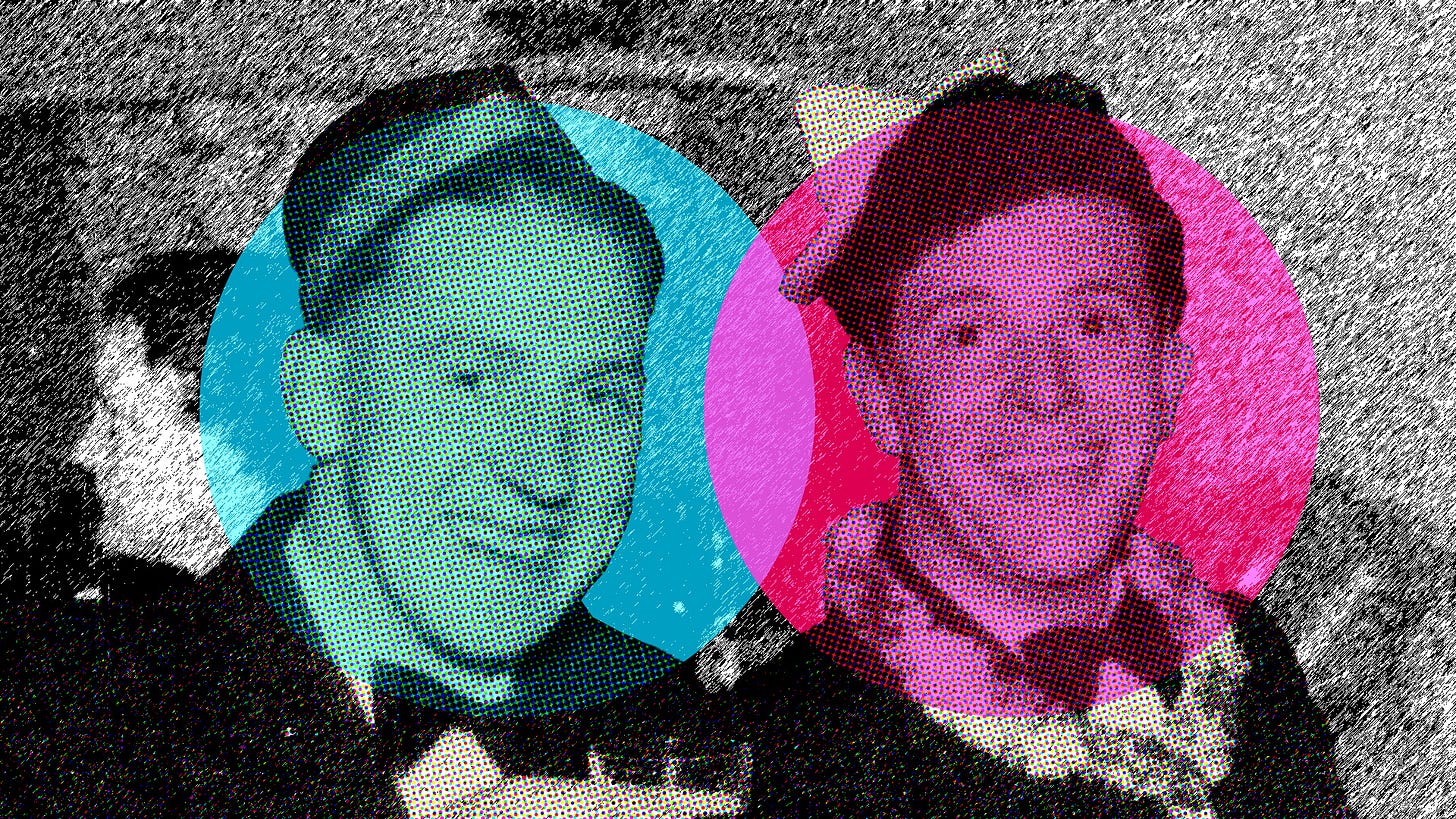

Loosely based on the early life of Guy Burgess, one of the Cambridge Spies, Another Country (1984) is about the 1930s schooldays of Guy Bennett, played by Rupert Everett. (We are strongly encouraged to believe these events occur at Eton, although the school is never named.) Bennett cares about three things: his own advancement up the greasy pole of authority and privilege, first at school and then (he confidently expects) in government; his best friend Judd (Colin Firth - we’ll get to him in a moment); and his schoolmate Harcourt (Cary Elwes), with whom Bennett conducts a prim romance that in 1984 felt rather transgressive. (The most they do on camera is snuggle in a punt.)

Hush-hush sexual exploration in this all-male environment is largely tolerated by the ‘Gods’, the older prefects in charge of school discipline, but Bennett actually loves Harcourt and essentially shimmies around the school singing ‘I Am What I Am’. When the Gods begin a crackdown on ‘beastliness’ following the suicide of a young man who’d been caught in flagrante with another student, Bennett feels invulnerable, believing that his class and charm will see him right. Instead, he is caned and stripped of his school privileges, a painful betrayal that sets him on the path to Moscow.

Another Country stands up surprisingly well on re-watching. It’s beautifully put together, quite short and spare and focused, and - without wishing to get all Ben Elton on you - it explains an awful lot about the kind of men who often end up running the country.

At the time, I was so transported by it - by the male beauty and the tragic doomed love and uniforms and Parry’s ‘I Was Glad’ and creamy stone and soft English countryside - that I couldn’t really see it at all. Almost literally so: I watched a videotaped version so frequently that the tape wore thin. I didn’t quite appreciate what a stern little moral fable it is, how perfectly it skewers what is wrong with public schools, or how very good Everett is in the lead role.

I didn’t realise the film is about the ruling castes of England, how the public school system breaks and betrays the boys who pass through it. (I was being remarkably obtuse, because St Paul’s School was doing a pretty good job of breaking and betraying my brother at the very moment that my obsession was peaking.) Instead, I thought it was about Russia and Communism. I was so deeply in love with Colin Firth - who is very young and just spectacularly beautiful in this, and whose character Judd is a Marxist - that I would have joined the Party if I thought it would get me any closer to him. As it was I borrowed from the school library a biography of Lenin (disappointingly unfanciable, although Trotsky was alright if you squinted).

I’ve never really stopped loving Colin Firth. But the other thing about Another Country that I’ve never really got past is a seamy predilection for depictions of teasing, affectionate, platonic male friendships, which runs alongside and is doubtless related to my utter lack of interest in watching men fuck (each other or anyone else). In Another Country, Judd and Bennett have a relationship of love and trust that runs in parallel with Bennett’s actual, physical romance with Harcourt; their dialogue throughout is the kind of provocative, casually revelatory banter that men seem to (or feel compelled to) specialise in, and after Bennett is whipped, it is Judd rather than Harcourt who responds with a righteous fury. (Deliciously, Everett and Firth have a real-life friendship that began with Another Country.)

Since then, I’ve retained a fervent interest in depictions of men’s camaraderie. From war stories to Westerns, Morecambe and Wise to Top Gear, Life on Mars to Band of Brothers, I’ve consumed and enjoyed them all. It’s a trope that’s both hegemonic and barely remarked upon (or barely remarked upon because it is hegemonic, the water in which we swim). Sure, people talk about ‘buddy movies’ and ‘bromances’ but there’s very little acknowledgement that male friendships in various forms are perhaps the single most powerful cultural and social unit, inside and outside fictional worlds. What was Brexit if not a by-product of longstanding close relationships between Cameron, Johnson and Gove, forged at school and university?

Real-life friendships are even more compelling than their fictional counterparts, because of their depth and complexity and actually-existing jeopardy. Like many people my age I grew up with Adam Buxton and Joe Cornish - real-life friends who’ve known each other since (public) school - and when Joe left their joint radio show for a new career in Hollywood I was gripped by the resulting psychodrama of sadness and reinvention, which Buxton explored without embarrassment in his solo podcast. (‘Are Adam and Joe still friends?’ suggests the Google autocomplete, plaintively.) Mark Kermode and Simon Mayo have a running joke that Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is not really about spies, but is instead a study of betrayal. But here’s the thing: their film review show, hosted for nearly 30 years on the BBC and now an independent podcast, is not really about movies. It’s about their friendship, a fully-textured thing of griping and irritation as well as concern and affection.

I’m not quite sure why this relationship model affects me so much. There’s a poignancy, probably borne from rarity, in men voicing their emotions to each other. And there’s something easeful and eye-opening about seeing how men behave when you are not on their radar; when they’re not trying to screw you or impress you or best you or squish you. Men engaged in active friendliness towards each other - men not thinking, even a little bit, about sex - are at their least threatening and most accessible.

It would be dishonest not to admit the influence of internalised misogyny. There are great all-female podcasts (Fortunately with Fi Glover and Jane Garvey) and girl-gang movies (Sisters with Tina Fey and Amy Peohler) and talented female comic acts (Wood and Walters, Smack the Pony) but I just don’t find them compulsive in the same way. I’d like to claim that this is because I don’t need to be shown what women’s friendships are like - I have plenty of scabrously indiscreet and emotionally splashy friendships of my own to be getting on with - but the truth is I also have a much lower tolerance for women’s work, voices, imperfections and oh, I don’t know, existence.

And it’s also about watching power up close; being accepted - if only as an observer - into a secret society where all the rules get made, and being reassured that they’re really quite decent chaps and everything will probably be totally fine. It's compelling in the same way that it used to be compelling to overhear my parents having private conversations about us as children. It makes me feel safe and comforted, mildly titillated and totally passive; it requires nothing from me except my attention. It’s infantilising and unhealthy - rather like repeatedly electing Old Etonians to run the country - but apparently I’m going to carry on doing it anyway.

For more on the (doubtful) idiosyncrasies of the British education system:

Superb read! Never seen the film and now totally inspired to do so.

What a fantastic piece. You will be thrilled?/distraught? to hear that I saw the play in the West End with D Day Lewis as Guy Bennett *and that we went to the stage door afterwards and told him we thought he was 'awfully good' and he said 'thanks'.*

My interest *was* erotic (in the peri-pubertal way of 'pashes' etc). I think this is now a recognised 'thing' in girls, with a dedicated Manga genre: https://savvytokyo.com/boys-love-the-genre-that-liberates-japanese-women-to-create-a-world-of-their-own/)

But there was also a kind of sexualisation or fetishization of class in the ether at that time - cf Tatler, and an obsession with glittering balls (dance ones) and brittle decadence. And at the very top, Brideshead Revisited, featuring both sexy upper classes and sexy near-sex between beautiful boys, and with which the whole culture seemed to be obsessed in 1981-2. My entire girls' school form was *agog* at that one, and at least two or three trailed around with their own Aloysius bears.

I cannot imagine sexing a Tory now, obviously.