An occasional series looking at popular stories of Doctor Who, a peculiarly British kind of TV hero, and the cultural contexts that influenced the ever changing character and his stories.

On second thoughts, let’s not go to Camelot.

‘Tis a silly place.

King Arthur, Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975)

1975

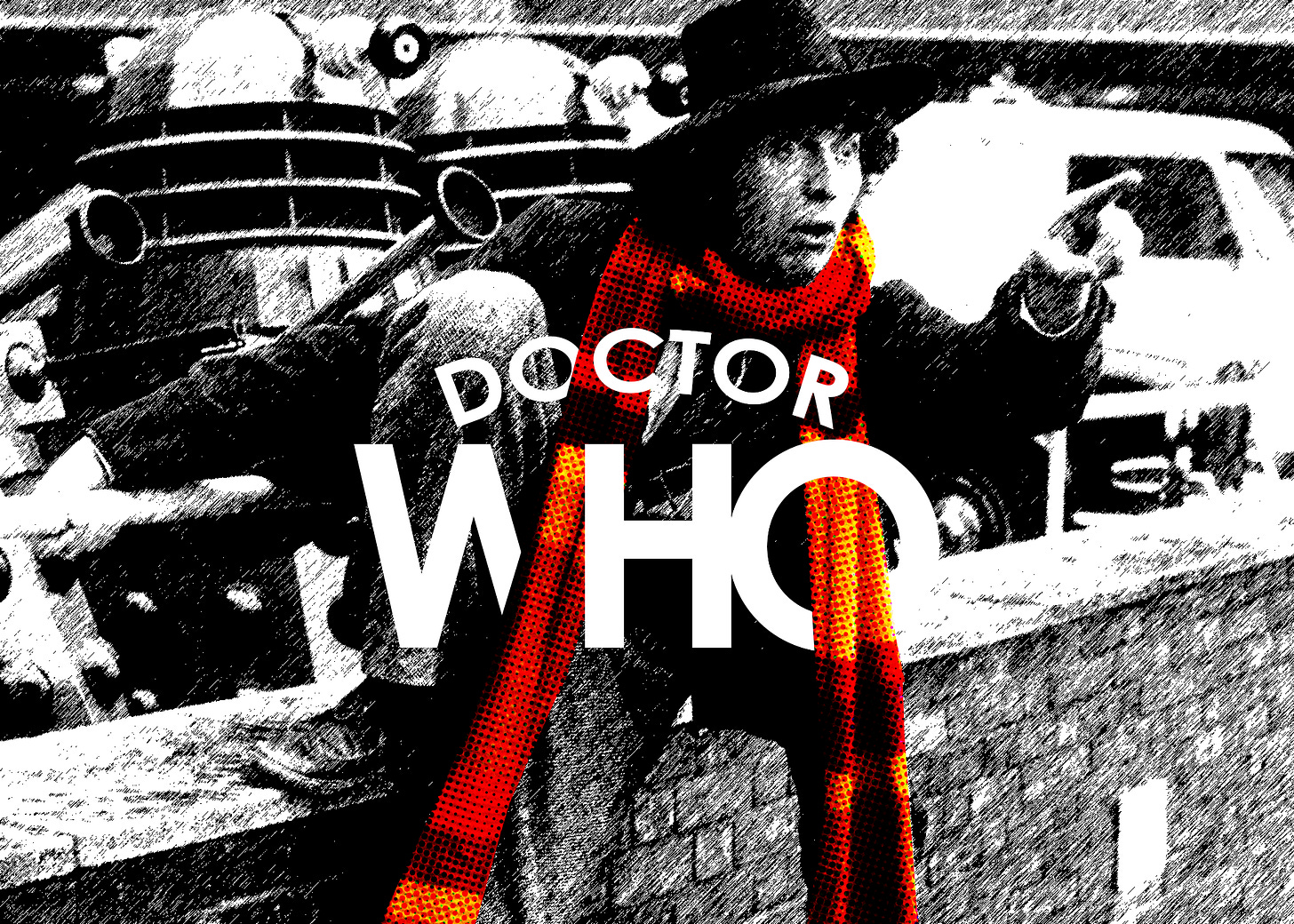

Britain in 1975 is a silly place, and full of silly men. At the cinema it is the year of both Monty Python and the Holy Grail and The Rocky Horror Picture Show. TV is ruled over by Eric Morecambe and The Goodies, and the gloriously, splendidly silly Tom Baker is the new Doctor.

This is both the raving of a country at the end of its tether, having just endured the Three Day Week, and also a vision of a country more at ease with itself, getting over the fever of a ‘60s adolescence and settling into a slightly daffy middle-age.

The Genesis of the Daleks

6 episodes, colour, March to April 1975

Starring

Tom Baker as the Doctor, with companions: Harry Sullivan, a naval medic and, at last! Sara Jane Smith, a reporter (on a magazine called… Metropolitan. Didn’t know that when we named this newsletter but by crikey it's a lovely coincidence)Synopsis

The Time Lords send the Doctor back in time to the planet Skaro with a mission to stop a great evil. He finds himself caught up in a war between two races, so devastating that it has set back science generations, and to which the mad scientist Davros has an unlikely solution: inventing the Doctor’s arch-enemy, the Daleks.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail

92 mins, colour. Directed by a brace of Terrys.

Starring

Clever Python, Tall Python, Welsh Python, Charming Python, Canadian Python, Pointless Python and Neil Innes.Synopsis

92 minutes of long-winded debate over the haulage capabilities of swallows. And some light mockery at mediaeval epics.

Well, here he is. Large as teeth and twice as alarming. My Doctor.

For several generations of a certain kind of British adult, it's how we classify each other: who was your Doctor? Tom Baker was mine. On the school run, my mother would entertain me with long, improvised stories about the Doctor, and that Doctor was and could only be Tom Baker (with Liz Sladen as Sarah Jane, of course). He was a letraset on the back of the Weetabix box at breakfast and the Target novelisation I read at night instead of sleeping. He arrived in the role when I was five and left when I was eleven, pretty much the entirety of my Doctor Who watching childhood. And I watched a lot of Doctor Who. I was a TV child, and Tom Baker was my TV dad.

He was a very ‘70s kind of dad. Every Saturday he would bundle the kids in a malfunctioning, rickety vehicle, a time-machine by way of British Leyland, and take them to a quarry somewhere in the suburbs, where he would absentmindedly let them play with dangerous equipment, only intervening to stop them killing themselves. Most of the time.

He was also, in the great tradition of ‘70s dads, very silly. In his first episode, having just transformed from being Jon Pertwee, he dances, sings and dresses as a Viking, all with a delighted, manic glee. Where Pertwee was all crushed velvet suavity, hovercraft and Venusian aikido, Baker is daft. He is impertinent and impatient, off-hand and off-subject, and his pockets are full of yoyos and jelly babies. He is constantly wrong-footing galactic despots and monomaniacal monsters by simply refusing to take them seriously.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Metropolitan to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.