The Bagshot Formation

Things you find out when you’re walking the dog

Around 65 million years ago the continents of Africa, Arabia and India crashed into Eurasia. This caused the formation of the Alps — an event that geologists call the ‘Alpine Orogeny’ — and also disrupted the bedrock across Eurasia. A large area of what is now southeast England collapsed and sank, forming a depression called ‘the London Basin’.

At this point (the dating of these events is extremely hazy) most of Britain was covered by the sea. Oceanic sediments and silts — basically, sand — sank to the bottom of the low-lying London Basin. When southern England emerged from the waves millions of years later, this sand was left behind. Over the millennia some of it has been eroded or blown away, but in other places it’s there to this day. These sandy outcrops many miles from the sea are collectively called ‘the Bagshot Formation’, after a small and strangely sandy town in deepest Surrey.

I found all of this out because I’ve spent much of the last eight months looking after my father’s dog.

Before I became a dog foster mum, I’d been vaguely aware that the soil around my part of the world was distinctly sandy; you notice this sort of thing when you’re the person who cleans the floors. But when I began taking the dog on regular long walks, the amount of sand started to really weird me out. We’re not talking about a sprinkling; there’s absolutely piles of the stuff, lying feet deep on footpaths and forming big natural sandpits where children sit with buckets and spades. Eventually I was driven to the ‘Local History’ section of Walton on Thames Library in search of an explanation, which is how I found out about the London Basin and the Alpine Orogeny and the Bagshot Formation, all of which would be good names for a band.

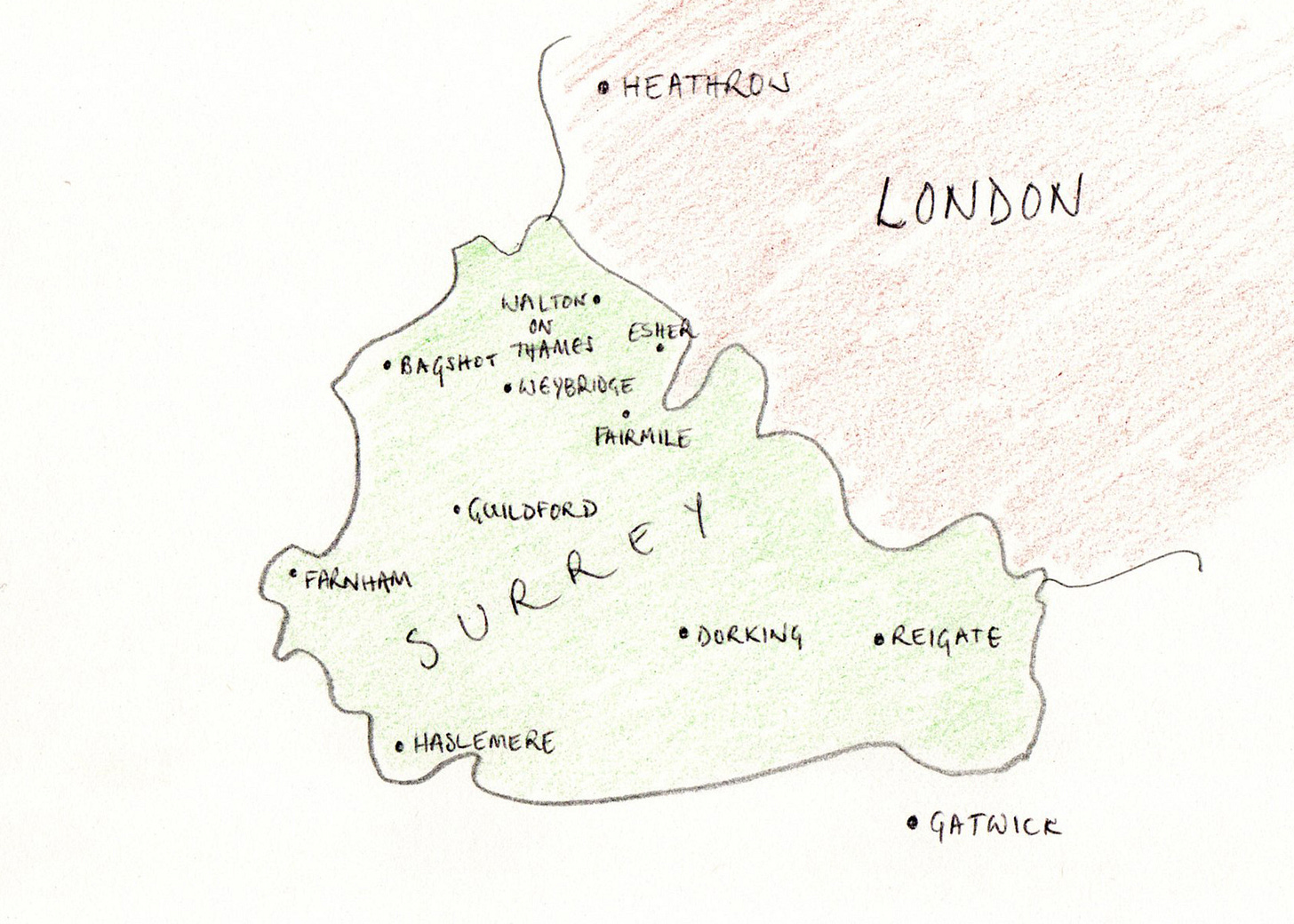

I’ve lived here – a village/suburb (subbage?) just over the Surrey border to the southwest of London – for nearly 20 years, and have resented every single one of them. We’re not even in the pretty bit of Surrey; that’s further south and west. I know I’m very lucky to have a stable home and a garden and a mortgage and all that jazz, but I’ve chosen the world’s most blah place to have all of those things in. Where do you live? Surrey. Whereabouts? Between Esher and Weybridge. Oh, nice! Well, I wouldn’t go that far.

But they say, don’t they, that dogs make you appreciate the small stuff. This is partly because they’re constantly delighted by miniscule things: letterbox spam, half a tennis ball, the reappearance of someone who left the room 10 minutes ago. Dogs have an absolute absence of churl, and it can’t help but rub off on you. But dog ownership promotes enjoyment in more substantial ways too. Ever since we accepted a spaniel into our hearts, my perception of my objectively stupid bit of the world has changed. I mean, I still think the pubs are rubbish and the architecture is dreary; but my appreciation of the things around me has expanded, as has my capacity to find them interesting.

Admittedly, some of this is because walking the same dog in the same places is extremely boring. (It’s honestly a lot like having toddlers. I think a lot about the cartoon of two women pushing small children on swings, and one of them saying ‘Don’t they grow up so slowly?’) The thing about boredom is that eventually it forces your brain to do new things. As you beat the same paths through woods and riversides day after day, week after week, month after month, even the smallest change can cause considerable excitement. All through the winter you pass the same unremarkable twiggy shrub and then suddenly, one mild morning in February, you see it is covered in tiny buds, and for the first time in your life you think: oh wow, spring is coming!

And that’s when you know that the dog has got to you.

Areas within commons and woodlands have local character; they are as distinctive as the nice bits and the rubbish bits and the student bits of your town. Once you’ve noticed their distinctiveness — once your brain has stopped thinking ‘that’s a random bit of green among a million bits of green’ and instead starts registering discrete places — you find yourself coming up with names for them.

In our small local riverside park there’s a low-lying grassy corridor that Tobias and I call ‘the Avenue’. From October to April the Avenue is thick with mud, which makes it one of the dog’s favourite places. (We are forever passing other dog-walkers who look at our dog, dip-dyed in blue-black filth, and say merrily: Oh dear! But the joke is on them, because our dog is the best one.)

In the summer the mud in the Avenue disappears, but while the grass in the rest of the park grows leggy and yellow, here it stays short and lush. Through droughts and heatwaves, right through the dusty fag-end of August, the Avenue is a vibrant green. It never, ever dries out completely.

This is because the Avenue marks the course of a small subterranean stream that used to feed a pond on our village green and flows into our local river, the Mole. The stream is still there, under the ground, and when the water levels are high the Mole floods into the old channel. That’s why it’s so muddy, and why the grass here remains green all summer long.

If I didn’t have to walk the dog, I wouldn’t know this.

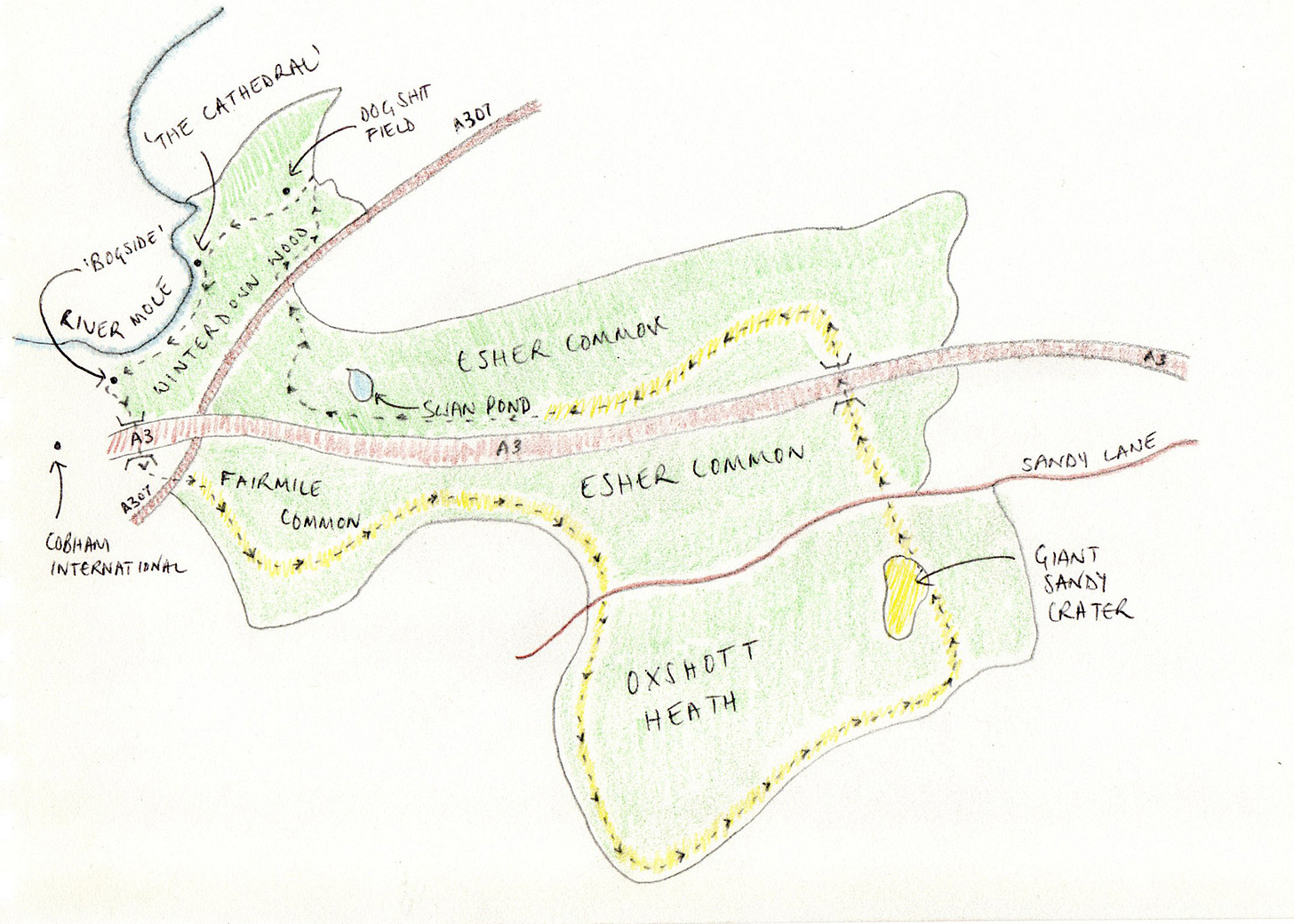

Our local wood, Winterdown, lies just over the Mole from the Avenue. Up on the high ground overlooking the river there’s a stand of tall trees. They have been planted reasonably evenly, and wherever you look they reform before your eyes into a kaleidoscope of arboreal corridors, like you’re stuck in some sort of National Trust Matrix. We call this area ‘the Cathedral’.

Beyond the Cathedral the land pitches downwards to meet the river. This is ‘Bogside’, because of the sulphuric riverine mud that lies beneath the ferns. Then you climb a small hill that suddenly opens out onto a sandy heath overlooking Cobham International School, and cross a strange rickety bridge over the A3 to reach Fairmile Common, where the Diggers tried to practise proto-communism in the 1650s before having their arses kicked to Walton on Thames and back again. From Fairmile you can walk to the sandy moonscape of Oxshott Heath and then back through Esher Common, where there is a lake in which a dog can swim if the two resident swans are looking the other way. From there it’s an invigorating dash across the busy A307 back to Winterdown Wood, where we started.

We call this route ‘the Full Monty’, and I’d lived here for 17 years before I knew it existed. I knew that the Diggers’ first settlement had been in Fairmile and had wanted to have a look, but (as you can see from the map above) the whole area is crisscrossed by major roads, including a 70mph section of the A3. Ordinary maps don’t make it obvious that there are safe ways get to Fairmile by foot. Happily, Tobias pays for the Ordnance Survey app, which revealed a crucial set of pedestrian bridges and rights of way. The realisation that I can walk to this place, seven or so miles away, almost entirely through green spaces has entirely altered my conception of my local area, a conception that is no longer entirely defined by auto routes and my role as a driver. And all because of our desperation for a new place to walk the dog.

Bigger walks only beget more questions (the first of which is always ‘why are there no public toilets on this route?’) One day as we were doing the Full Monty I wondered aloud about Ordnance Survey, and whether it is a peculiarly British thing – whether other countries have this extraordinary level of topological and access detail, available to the public at near-cost price. (Broadly speaking: the UK is not the only country to have OS-style maps, but ours are some of the most comprehensive and widely used.) And then I wondered whether the existence of OS maps makes us particularly good at maintaining and defending public rights of way (signs point to ‘yes’.)

And then I wondered whether OS maps — which have existed in the public domain for nearly 300 years — presented any sort of potential security problem during the invasion scare of 1940, when the Nazis were sitting a few miles away from the London Basin, on the other side of the Channel, considering how best to get 100,000 men and a few thousand Panzers to London. Yes; it turns out that having freely available up-to-date topographical surveys of a country you plan to invade is very useful. For some reason this did not deter the OS team from producing in 1940 a whole new series of maps, the ‘New Popular Sixth Series’, which included brand new details about National Grid structures. I can only assume they were particularly popular in Berlin. All of which is yet another thing it wouldn’t have occurred to me to consider if I didn’t have to walk the dog.

For more summer adventures, there’s always Glastonbury:

Is the OSM free data up to date on footpaths in your area? At first glance

https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=16/51.36433/-0.39291 seems quite comprehensive.

I'm from a mining town in northern Canada. Many find it a boring place. This piece made me realize my town has in its shadows, a network of walking trails, easily found with topo maps on my phone. All this to say, you peaked my interest in learning more on UK's history of Ordinance Survey OS and realizing my town may not be so boring after all.