That’s just, like, your opinion, man

A question of taste

Along with some other members of The Metropolitan extended universe, I am a member of a WhatsApp group dedicated to listening to and discussing the albums featured in the Pitchfork Sunday reviews (I know, I know, positively caricatures of ourselves at this point).

A recent record was Alice Coltrane’s Universal Consciousness, avant garde devotional jazz of the most kitten-on-the-keys kind. Suffice to say, I did not enjoy it. To be honest I barely listened to it. It was on, I was there when it was on, but I heard next to none of it, at least in part because I didn’t understand it at all but mostly because I didn’t like it. I ended up with nothing to contribute to the discussion.

But it did make me think a lot about taste.

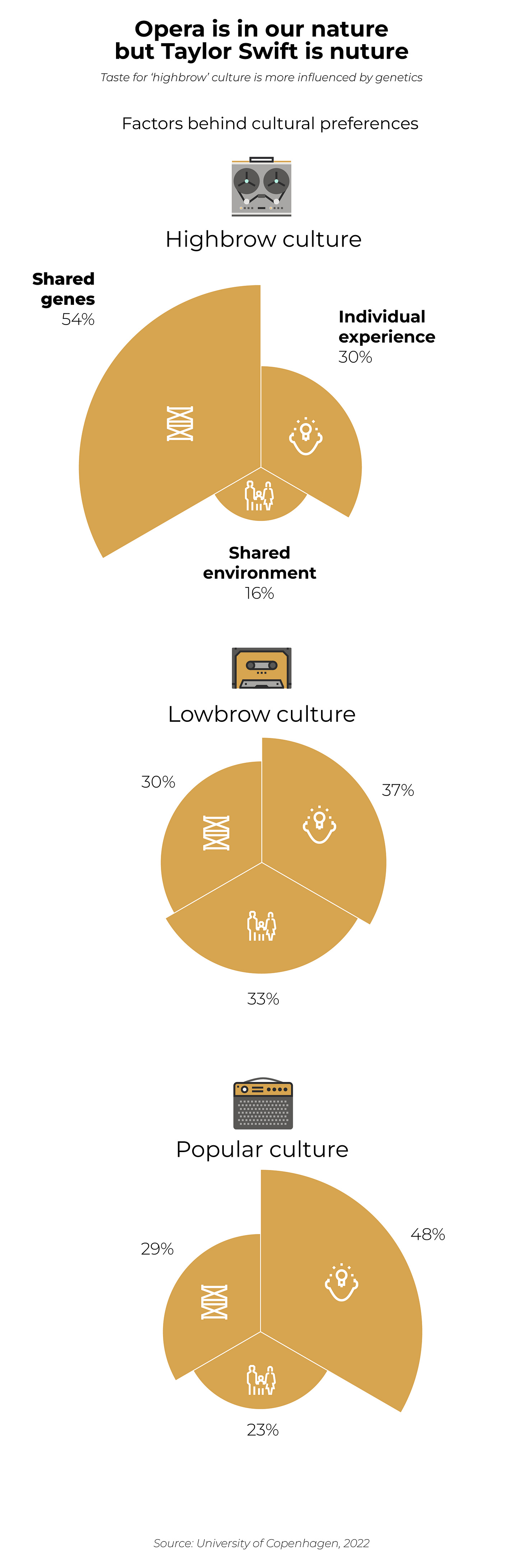

According to a study by the University of Copenhagen, cultural taste is influenced by three key factors: culture, upbringing and genetics. They claim that our taste in ‘lowbrow’ culture is equally influenced by all three, while our taste in ‘highbrow’ culture is more influenced by genetics. Meanwhile, our taste in popular culture is most influenced by our individual experience; what popular culture we like is influenced by what popular culture we’re exposed to by popular culture, which is perhaps not the most surprising insight.

Obviously we might cringe a little at notions of ‘highbrow’ and ‘lowbrow’ culture. The researchers seem to be classifying ‘highbrow’ as things like classical music and ballet, while ‘lowbrow’ is… checks data section of the paper… ‘cattle shows’? Well, ok then. This is why the Danes went a-viking, I guess, to find something more interesting to do. Or steal the Anglo-Saxons’ cattle.

Anyway, we might at least be able to agree that some works or forms of art can require more active, intellectual engagement than others. And the willingness to engage in conscious thought is apparently a heritable trait. Indeed, it gets called ‘need for cognition’: some people actively want to think. They require it in order to be happy.

But we might at least agree on those contributory factors: culture, nuture and nature. They certainly feel right. I have the sense that I have a set of innate tastes, a fundamental heuristic for liking things, my own personal mainstream. I am not very musical, for instance, I like dominant rhythms and simple melodies. This seems inescapable and the kind of thing that predisposes me to not like Alice Coltrane.

But this basic taste is then inflected by my culture and upbringing. My father loves the music of Sibelius, so I got an early exposure to Romantic classical music, all those big, memorable tunes, and I grew up in the ‘70s and ‘80s, surrounded by the straightforward structures of punk and New Wave.

Is Sibelius ‘highbrow’ though? I’ve certainly hung out with enough classical musicians in my time to know the real connoisseurs love modernist twelve-tone that sounds like everyone’s playing from a different score and hasn’t agreed on when to stop, and mournful monastic medieval plainsong, not anything as obvious as Finlandia. That shit is for the bourgeoisie over on Classic FM.

And is punk ‘lowbrow’? Rooted as much in Situationist art theory as it was in three chord thrash, especially as it developed into post-punk and all the college kids started getting involved. Although I could imagine Devo playing a cattle show, it's true.

But both those contexts: my classical music friends and the nerds I met at University who introduced me to art rock like Sonic Youth and Talking Heads (the individual in question also had a John Coltrane poster on his wall), hint at how important that third influence really is. The ‘individual experience’, our own encounters with popular culture through the influences of friends and fashion and the formers of taste.

The researchers of that paper are anxious to point out that taste has very little correlation with talent. Having musical talent does not guide one's taste. This, again, feels true; one may be a brilliant guitarist and fall in love with jazz like Django Reinhardt, or making weird squealing noises like Joey Santiago of Pixies, or indulging in long, tedious guitar solos in lumpen and predictable blues rock like Eric Clapton.

But it must have some impact on the way that one’s taste develops, that individual experience. Take Alice Coltrane herself. She came from a musical family: her mother sang in a choir and both her brother and sister went into the music business. She had the shared experience that no doubt shaped her musical taste, in jazz and in spiritual music.

But then she also had an individual experience that must have been deeply influenced by her talent. She ended up going to Paris in the ‘50s to study classical music and jazz; and where better to do such things in the 1950s? That milieu would have exposed her not just to specific kinds of music but to people highly engaged in thinking about those kinds of music.

The researchers of that paper on musical taste were also looking at cultural omnivorousness; how interested people were in finding and investing in unfamiliar cultural forms. This is, again, no doubt related to another trait thought to be genetically inherited: how interested one might be in new experiences.

If you’re deeply involved in a particular art form, probably through talent, that need for novelty is going to result in the development of avant garde ideas, the impulse to innovate and disrupt. You will be cursed with knowledge, your heuristics for what is normal and straightforward will be completely warped by the depth of your experience.

The charts I’ve used in the infographic above are a good example of this. I’ve used polar area charts, my absolute favourite. Also known as the Nightingale Rose, they are charts that changed history when Florence Nightingale used them in her report to Parliament about deaths from disease in military hospitals in the Crimean War. This kind of background is common knowledge to me. I teach data visualisation, I’ve co-written a text book on how to do it. Thinking about charts and how they work is all I do all day, so of course I look for something unusual as a change to boring old bar charts. But most of you are probably just thinking I don’t know how to make a pie chart.

All professions inevitably become ‘conspiracies against the laity’, as George Bernard Shaw put it, simply because of this expert common knowledge. All creative practices and art forms constantly generate an avant garde, practitioners and participants who are bored of the old tropes and ever more abstruse and occult in their tastes.

And I do mean ‘occult’. This happens in all strands of human creativity, including spirituality. Alice Coltrane’s Universal Consciousness melds together different spiritual traditions, from the Judeo roots of Christianity in ‘Battle At Armageddon’ to ancient Egyptian symbolism in ‘The Ankh of Amen-Ra’, both of which are references to what we might term the avant garde in religion.

Armageddon, the final battle with the forces of darkness at the end of time, features heavily in the Revelation of St John of Patmos, easily the battiest book in the Bible, a heavy hodge-podge of eschatological symbolism and hallucination. And while Ra may have been the chief god of the Egyptian pantheon, he’s hardly the subject of daily discourse. We’re more of an Aesir and Olympians household.

Musically, conceptually, spiritually, the whole album is avant garde. Coltrane might have been influenced by her mother’s church music, but her experiences, shaped by her own talent and the people she knew, have developed it in an extraordinary direction.

And this is the thing. Tastes develop. This is where that individual experience crosses that genetic predisposition. The researchers of the paper themselves suggest that the influence of individual experience on tastes in popular culture is because pop culture changes, is constantly throwing up novelty, and so our reactions to it change too. The world changes, we change, our tastes change. Never trust someone who still only listens to the music they liked when they were a teenager.

I listen to Mahler and Schubert more than Sibelius these days. I don’t listen to Sonic Youth as much, except as a nostalgic indulgence. I’ll never stop listening to Talking Heads, but that’s just normal and right. If you had played me ‘Tsuginepu’ by Asa-Chang and Junray as a teenager I would have experienced it with the incomprehension I still feel for Alice Coltrane, but forty years of listening to music has changed my tastes:

Of course, I would have to admit that it took me a few listens to learn to like it. It struck me as interesting immediately, but it was foreign and unusual in its language and rhythms and construction. I had to want to like it in order to persevere.

This, I’ll admit, is pretentious. I was trying to become someone I wasn’t yet, someone who liked Asa-Chang and Junray. This is a form of influence on taste that is usually derided, this kind of ‘aspirational’ taste. ‘Pretentious’ is, after all, an insult. People who try to like things just to appear cool are looked down on, people who only like things because their friends do, because someone they admire likes it.

But aspiration plays a key role in how our tastes develop. Status seeking and forming friendship groups are fundamental behaviours for social apes. As the researchers of that paper point out, social relationships are key to our tastes. New friends introduce us to new things. They are friends, after all, because they share some degree of world view and taste but they are new and have different individual experiences. We find a radio DJ we like, a cinema with a nice bar, a bookshop with an inviting window display, and through them we discover new things.

I recently wrote about the movie Easy Rider (1969) and was not entirely complimentary, which led to a large number of Boomers appearing in the comments to shout at me. Apparently I didn’t like their movies because I didn’t understand them. But I only ever watched it in the first place because Boomers had shouted at me. Countless articles and books and documentaries had impressed on me how Easy Rider was the cultural event of the late sixties and the beginning of New Hollywood. I was bound to have high expectations and they were bound to be disappointed, because I’m of a different generation. I could never truly understand it.

That post Second World War generation had an unprecedented cultural impact, not just because of the political and social milieu but also because of the media environment. There was genuine mass media, but not yet the unconstrained and limitless firehose of the Internet. In this country there was the BBC, with a near hegemony over broadcast channels on radio and television. This gave a means not just for creation but, perhaps more importantly, for curation.

John Peel played us interesting music, Alex Cox showed us interesting films and Melvyn Bragg introduced us to interesting artists. Of course, you might not like every fifteen minute dub reggae track Peel played, and Peel himself might despair of the dull, guitar heavy tastes of his listeners, but the aspiration of being the sort of person who listened to Peel meant you eventually became the sort of person who listened to John Peel and discovered new music.

This doesn’t always work, of course. I might want to become the sort of person who listens to Alice Coltrane but I suspect that Universal Consciousness is just never going to be to my taste. However much one might be introduced to the new and the avant garde, it still has to chime with that instinctive, personal taste. But when it does, that is precisely when one’s tastes develop and change, when one’s world opens a little wider and new possibilities are revealed.

And as below, so above. This is how culture changes too. Easy Rider was important in beginning to introduce the avant garde styles of the European Nouvelle Vague into American mainstream cinema. Not just the visual immediacy of handheld cameras and inventive editing, but also the street level viewpoint and the attempt to capture reality, not Hollywood fantasy.

Alice Coltrane was apparently an influence on Radiohead, who, like Nirvana before them, have played a crucial role in bringing the tropes of avant garde post-punk into mainstream rock.

The very term ‘avant garde’ contains this promise: it is the vanguard of culture, breaking the ground into which the mainstream will eventually flow. When the avant garde finds resonance in the mainstream, then mainstream culture develops and the world is changed. And when the world’s tastes change, our taste changes too.

Last Sunday’s review in Pitchfork was Kate and Anna McGarrigle’s eponymous 1976 album. It includes a version of Loudon Wainwright III’s ‘Swimming Song’. I was a big fan of Wainwright when I was a teenager but my tastes have changed. I much prefer the McGarrigle’s version now.

Liking the ‘right’ music can be an important social marker. Sadly.

You nailed one brilliant line in there "I had to want to like it". Says so much about the complex process. Who "wants" and who "likes"? Some über-ich wanting something the ich should do? And so much more thinking along those lines. Thanks!

P.S. And you are right, you listening to and discussing pitchfork reviews is deeply incestuous :)

So brilliant. I think it’s brave to grow intentionally. And at the same time I also think it’s mature to know when you just don’t give a shit about what you’re being told is avant garde because you know it’s just dumb.

What I have been made aware of recently is how very little I actually recognize is of my own taste. I’ve been, per the recommendation of a friend, writing out a list of what I like, and doing so in the third person so it is an objective list.

To that end, I, as a former opera critic, wonder what the fuck Copenhagen would think of the first item on that list: my second-hand Ford F150 pick up truck with the extended bed, meaning my truck is that much bigger than everyone else’s. Also, my predilection for only drinking French wine even if West Coast US wines are better, and the fact that I love fried dill pickles.

And to me, none of this is incongruent. Also, I have NOTHING in common with my family. I like nothing they like, and vice versa.

I mean, the Danish would frame things that way because they are the last bastion of hegemony in Europe. So seeing things in such a categorical way is in their genes, you could say.