We were raised by Puffins. With three TV channels and no internet, for long stretches of our lives reading was the best (and sometimes, the only) way to pass the time. Here we return to the books that made us and analyse what makes them great.

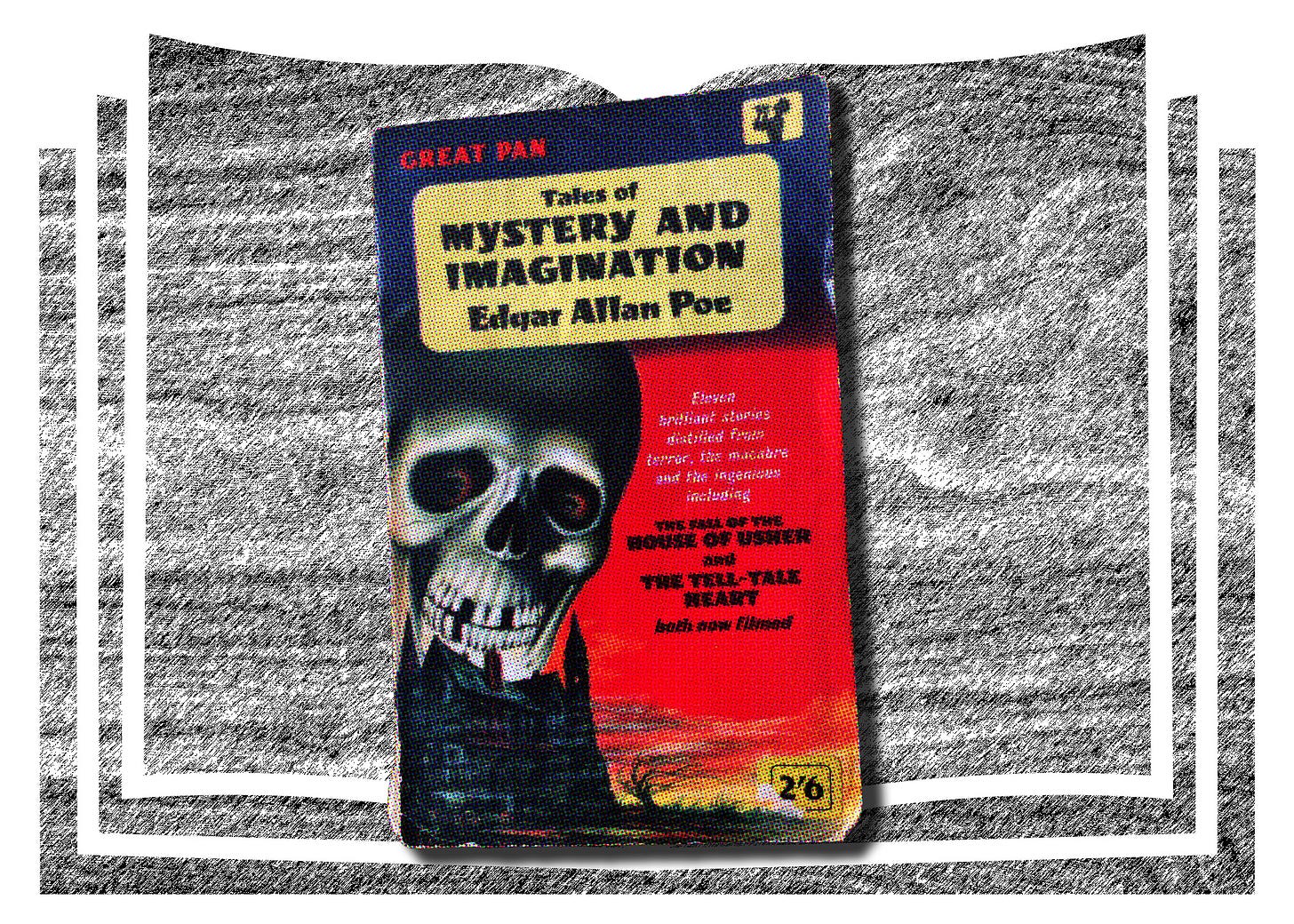

The title ‘Tales of Mystery and Imagination’ has been used for various posthumous collections of Edgar Allan Poe’s short stories. These collections usually contain doomy gothic weirdnesses (‘The Fall of the House of Usher’, ‘Ligeia’), detective stories (‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’, ‘The Purloined Letter’), tales of psychopathic revenge (‘The Tell-Tale Heart’, ‘The Cask of Amontillado’) and puzzle-driven mysteries (‘The Gold Bug’).

Tales of Mystery

When we found ourselves stranded in Philadelphia by snow, m’colleague Adam and I had to find some way to pass the time until we could get on a flight home. We ate cheese steaks and scrapple, went to look at the Liberty Bell and the Rodins, and toured the Penitentiary and the Mütter Museum. I have never seen Rocky so the outside was lost on me, but the inside of the Philadelphia Museum of Art is excellent.

We also went on a pilgrimage to find the houses of two of America’s great conjurers of the uncanny, because Philadelphia — the city of brotherly love and rational government — was also some time home to both David Lynch and Edgar Allan Poe. This, the city of eagles and bells, is where Poe wrote ‘The Raven’, the poem that made him famous.

‘The Raven’, though, is not how I know Poe. I get the impression he is something of a national treasure in the States, but he was not taught in England when I was at school. I had to discover him for myself, and I discovered him through his stories, collected in an edition of Tales of Mystery and Imagination.

This made him something of a mystery. He was not of the canon of literature I was being taught. He was from the wrong continent, and was somewhere in between the solitary fancies and conscious archaisms of the Romantic poets, and the teeming streets and grim realities of the Victorian novelists.

His style straddled these influences. The prose of ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ (1839) is as obscure and convoluted as the monstrous house and monstrous people it describes; its paragraphs are as cluttered as a Victorian sitting room, full of dark furniture and unexpected impediments to progress. ‘The Masque of the Red Death’ (1842) it is a story of strange and disconcerting vibes, set in the no-place of the gothic, outside of real history or geography, and infected with a sense of creeping wrongness that sickens the narrative until it can bear it no longer and ends in a sudden swoon.

The style of ‘The Tell-Tale Heart’ (1843) on the other hand, is horribly stark, the meticulous unreason of a disordered mind (‘why will you say that I am mad?’) captured in nervous, hectic thoughts. Rather than mazing you with an inchoate uncanny, the immediacy of the narrator forces you into the horror, first hand and all too real.

But the real mystery was the man himself. The strange trajectory and the many miseries of his life make him the goth-father. As famous in his lifetime for his acid criticism as he was for his doomy verse, he was the ultimate self-aggrandising, self-pitying, vituperative and wounded young man. As Wikipedia summarises it: ‘He is the first well-known American writer to earn a living exclusively through writing, which resulted in a financially difficult life and career.’ Same as it ever was.

His life was one of his stories; or, his stories were his life. He was the child of actors, but by the time he was three his father had abandoned him and his mother had died. He was taken in by the wealthy John Allan, who forced his name into the young Edgar Poe’s. This was both a gift and a proprietorial imposition, which appears to neatly summarise their relationship. His life after this point was a series of fallings out with authority figures, publishers, other writers, and the Army.

Then there was the disturbing marriage to his 13-year-old cousin Virginia Clemm when he was in his twenties, and his descent into alcoholism after her death at 24 from tuberculosis. Poe’s own death was considerably more bizarre: he was found unconscious in a Baltimore street, wearing someone else’s clothes, and didn’t regain consciousness long enough to explain what had happened to him.

His afterlife was a bizarre tale of revenge. His literary enemy, a man with the splendidly sinister name of Rufus Wilmot Griswold, managed to gain control of Poe’s literary estate and proceeded to try and ruin it, publishing a lurid biography and forging letters to ‘prove’ his lies. This served to make Poe even more mysterious, the truth of the man hidden behind a swirl of rumour and slander.

It backfired on Griswold in the end: as with Byron, the promise of thrilling stories written by a ‘bad’ man proved irresistible. It certainly was to me, a goth teenager stumbling across these stories in the school library. (It also helped that Poe had, like me, gone to school in North London.)

Tales of Imagination

According to Keats, reading George Chapman’s translation of the Odyssey was like being an astronomer who had discovered a new planet:

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star’d at the Pacific—and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

- John Keats, ‘On First Opening Chapman’s Homer’

Reading Tales of Mystery and Imagination for the first time was more like Speke and Burton following the Nile to its source, or, more appositely, Marco Polo travelling down the Silk Road to China, finally arriving at the court of Kublai Khan. All my life I had been consuming goods from this unguessed-at and fabulous land; finally I had arrived at the source of treasure and wonder.

A savage place! as holy and enchanted

As e’er beneath a waning moon was haunted

By woman wailing for her demon-lover!

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ‘Kublai Khan’

Romantic poetry is where Poe seems to start, but what follows him matters more. So much popular pulp fiction begins with Poe; if he did not invent it, he defined and refined it. This is particularly true of genres I loved as a small boy: tales of the uncanny, science fiction, detective stories. You can discern the atmospheric, lyrical creepiness of Ray Bradbury in ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’, the mounting dread and cosmic horror of H. P. Lovecraft in ‘The Masque of the Red Death’, and the twisted psychology and visceral gore of Stephen King in ‘The Tell Tale Heart’.

Jules Verne — who has a decent claim to be one of the founders of the science fiction genre — was deeply influenced by Poe’s proto-science fiction stories, and called him ‘le créateur du roman merveilleux scientifique’. Meanwhile, one of the few mysteries never investigated by Sherlock Holmes was how his whole character came to be swiped from Poe’s C. Auguste Dupin, the first in a long line of analytical amateur detectives.

One can even spot the structure of an old-fashioned point-and-click game in ‘The Gold Bug’ (1843). The story, which involves the decoding of a pirate code and the search for hidden treasure, inevitably reminds the twenty-first century reader of the puzzles in the game Myst (1993) or one of the more cerebral shrines in Breath of the Wild (2017).

I may be slightly over-reaching when I detect traces of the Joker in the motley-clad narrator of ‘The Cask of Amontillado’ (1846), but the transatlantic gothic of Poe’s stories has so saturated American popular culture that it’s hardly surprising there’s a Batman villain called ‘The Red Death’, and that Batman and Edgar Allan Poe have teamed up to solve mysteries in the comics. These dark and tormented East Coast orphans are all the same.

This was why finally reading Tales of Mystery and Imagination was such a revelation. The traditional image of Poe is of a lone, mad genius, the Bohemian stereotype of the artist. But in reading him I saw how storytelling was a process, a conversation down the ages, a handing on of ideas and tropes, to be adapted and renewed by each succeeding generation: from Medieval fabulists and Gothic novelists and Romantic poets to Poe, from Poe to the pulp writers and modern mythologisers who followed him.

Which is not to say that Poe wasn’t a significant and unique contributor to that conversation. In ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’, Dupin, the detective, delivers a paradox about chess and chequers. Chess, he says, is a game of complex rules that takes concentration and intelligence to master but which then becomes about those rules. The player is constantly thinking of possible moves, available strategies within those rules. They are playing against the game. In chequers, Dupin argues, one plays against one’s opponent. The game is so straightforward, the rules so simple, that a match becomes a contest of psychology, of context and understanding, of imagination and mystery. The simpler the rules, the more flexible the game becomes.

At first sight the short, creepy story seems much simpler than the complex literary novel, but Poe brings to bear his imagination and understanding to this apparently undemanding game and works endless variations. He works them into detective stories, or dream narratives, or horrifying psychology, or puzzle cracking games. And in doing so, he invents whole new forms for those stories to follow ever after.

This man, writing in the first half of the nineteenth century, defined many of the genres and tropes of the twentieth. Conjuring visions of an imagined and impossible past, he invented the pop culture of the future. Countless books and films and TV series and comics are still recreating his creations and developing his themes.

There, at the headwaters of all these widening tributaries of pulp fiction which have flooded the following centuries in their weirdness and fantasy, above a bubbling spring of imagination, is a bust of Edgar Allan Poe. And perched on it, a raven, who quoth, ‘Evermore’.

Spooky Victorian stories are possibly the best way of consuming horror: all the creepiness, none of the actual scares.

“The prose of ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ (1839) is as obscure and convoluted as the monstrous house and monstrous people it describes; its paragraphs are as cluttered as a Victorian sitting room, full of dark furniture and unexpected impediments to progress.” Nice zeugma, that.

The thing that surprised me about Poe when I first learned about him properly was just how early or out of time he is - as you say here, in between the glory days of Romantic poetry and the hue and cry of Victorian fiction, and so much earlier than the Conan Doyle/Bram Stoker stories among which his work seemed (to me at least) to belong. For cultural historians, the 1830s and 40s are a kind of no man’s land: not the 1790s and not the 1850s. Which makes them all the more interesting.