Secondary world

That’s no moon

As a toddler, one of my favourite games was collecting rocks. This involved walking slowly around the garden picking up pebbles and bringing them back indoors.

This is important evidence for the corrupting influence of the media on the young mind, because when I was a toddler, the TV was full of rock collecting. I was born in 1969 and grew up watching endless grainy black and white footage of grown men in bulky romper suits bounding gracelessly about in zero-g, picking up pebbles to bring back home. I was simply playing at being an astronaut on the moon.

The influence was profound. I ended up with a lifelong fascination with both real world space exploration and, as a protege of Doctor Who, Captain Kirk and Obi Wan Kenobi, of more fantastical interstellar shenanigans. Put a rocket in it and I’ll watch it – even when, as with so much science fiction and science fact, it's incredibly boring.

The Moon has always been a locus of dreams and fancy. Among other things, the Moon card in the Tarot represents the life of the imagination. It is a place of dreams and aspiration, a giant presence in our metaphorical firmament: we are ‘over’ it, we ‘shoot for’ it, we are ‘struck’ by it. But, over time, the Moon expeditions of the ‘70s reduced the wonder and glory, and instead began to feel like mundane jaunts to a nearby quarry. Alan Shepard of Apollo 14 played golf on the moon, like a mid-level executive on a work trip; the Sea of Tranquility became twinned with Surrey.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) epitomises this tension between thrilling fiction and turgid fact. Director Stanley Kubrick, following up his adaptation of Lolita (1962) and the nuclear war satire Dr Strangelove (1964), films of psychopathic emotion and dark comedy, plumbing the depths of the human experience, wanted to make a ‘good’ science fiction film. Looking for a story to work with he eventually arrived at sci-fi writer Arthur C. Clarke, a physicist and space travel expert who had popularised the use of geo-stationary satellites in telecommunications. They ended up collaborating to adapt Clarke’s story ‘The Sentinel’ into a whole new screenplay and accompanying novel.

The film opens with a group of prehistoric hominids scratching a precarious existence on the veldt. They are visited by an alien monolith; their leader touches it and – apparently as a direct consequence – goes on to invent tools, using a bone to bash in other hominid’s burgeoning brains. In the novelisation of 2001 (which Clarke wrote with Kubrick as they worked on the screenplay) this lead ape-man is called ‘Moon Watcher’. This is perhaps evocative of his role as a priest: observing the motions of heavenly bodies, communicating with the alien gods and their enlightenment-bringing monoliths. But Clarke was doubtless also thinking of him as a proto-scientist.

Observations of the Moon are the very beginnings of science. Among the incredible prehistoric paintings in the caves of Lascaux in the Dordogne region of France, there is a series of dots that are now thought to show the phases of the moon, the lunar month. Here we can find the origins of astronomy. This lunar observation also became the basis of our months and years. These dots represent the beginnings of our ability to measure time and, more importantly, to predict the future: to use imagination as a predictive tool, to conceive and plan for future events; to embark on agriculture, build cities, and so completely understand the movements of the celestial spheres that we can land a man on the Moon.

Arthur C. Clarke is a perfect example of the physicist as science fiction writer, explaining the science and predicting the future. It is the science fiction of Jules Verne, author of De la Terre à la Lune, who bitched about H. G. Wells’ later novel The First Men In The Moon because it wasn’t scientifically plausible enough. This approach arose at the origins of the genre. Hugo Gernsback, amateur inventor and editor of the early sci-fi magazine Amazing Stories, gave it as his mission statement:

‘Not only do these amazing tales make tremendously interesting reading — they are always instructive. They supply knowledge... in a very palatable form... New adventures pictured for us in the scientifiction of today are not at all impossible of realization tomorrow…’

At its best this form of science fiction is utopian; it foresees mankind’s challenges but also suggests solutions. (You see this in the ‘competence porn’ of Star Trek, as heroic engineers come together – as the lead character of Andy Weir’s The Martian puts it – to ‘science the shit’ out of difficult problems.) At the same time, it celebrates an Enlightenment-derived, reductive worldview that reduces wonder to facts; it sees the world in terms of resources and capabilities, and sees the Moon as a big hunk of unexploited minerals.

When such fiction talks of the human urge to explore and discover, it is hard not to think of the indigenous peoples of the Americas who were explored into death and ruin, the whales hunted into uncharted seas by obsessive capitalism, the discovery of enslavable populations and the new lands they could be forced to work. The Moon frequently features in sci-fi as a source of anti-colonial resistance, as in Robert Heinlein’s classic The Moon is a Harsh Mistress and Philip K. Dick’s utterly delightful Time Out Of Joint. However it is usually used as an analogue for revolutionary America, rather than home to an uprising of indigenous people against their oppressors.

Meanwhile there are other problems with books written by engineers. As the quote from The Martian might suggest, they are not always well written. They tend to be novels of ideas rather than of character, of scientific-paper abstract rather than elegant prose. And they are often read as treatises rather than as works of fiction. Indeed, readers often actively try to enact them; the crew of Apollo 8 told Clarke that they were going to tell NASA that they could see a monolith on the surface of the Moon.

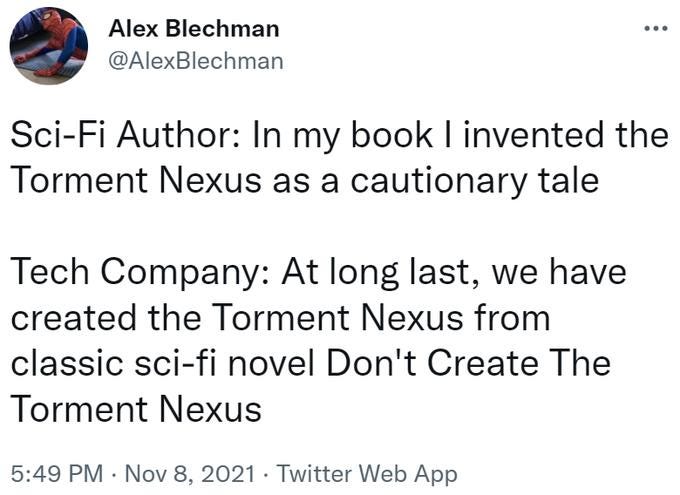

Sci-fi writer William Gibson, the inventor of the term ‘cyberspace’, has repeatedly complained that computer scientists have persistently misunderstood the dystopian satire of his cyberpunk books, set in a world where horses have gone extinct and the plutocratic 1% have forsaken the poisoned Earth to live in splendid isolation in orbit. More recently, Elon Musk has taken to naming his rockets after spaceships from Iain M. Banks’ Culture novels, suggesting that he has very much not understood the books’ themes of luxury space communism and militant social justice.

In 2001 Kubrick portrays the astronauts and physicists as deeply unpoetic, discussing sandwich fillings on their journey to see an ancient alien artefact. In one extraordinary scene the scientists on the Moon have an entirely pointless meeting in which they exchange bland boosterisms and don’t even mention the ALIEN MONOLITH they have assembled to discuss. Kubrick films almost all of this in a single take, in a wide shot from one end of the room so that we’re mostly looking at the backs of people’s heads. Every time someone speaks we have to watch them march ponderously up to the podium and back. He is determined to make us experience this stupid meeting almost viscerally, to make us truly feel the plodding tediousness of these scientists. It is brilliantly boring.

The only emotionally expressive character in the film is the computer, HAL 9000, who has a nervous breakdown and starts murdering the impassive humans around him. Clarke, in the novel, is anxious to explain HAL’s actions, to make sure we understand that he’s caught in a logic loop (his orders specify that he must keep the real reason for the mission secret from the rest of the crew). But Kubrick does no such thing. The film never explains why HAL starts killing people; Kubrick wanted the audience to engage imaginatively and find their own readings, not only of HAL but of the film and what it might mean. He deliberately creates an experience that is unsettling and challenging. He wanted to create a sense of the ‘awe and terror’ of the infinite through a film that ‘hits the viewer at an inner level of consciousness, just as music does’.

Given this, it’s significant that Kubrick approached both Michael Moorcock and J. G. Ballard to replace Clarke as his collaborator on 2001. Moorcock and Ballard were part of the New Wave of British science fiction; they were more interested in inner exploration than outer space. They explored what technology and post-Enlightenment civilisation was doing to human minds and souls. It makes sense that this appealed to Kubrick, who was, in this film, as interested in spiritual enlightenment and man’s relationship to the universe as he was in The Actual Enlightenment.

In 2001 the technological exploitation of the Moon leads to the discovery of a magnetic anomaly, which turns out to be an alien monolith, which then leads them to a portal in orbit around Jupiter through which the astronaut Dave Bowman travels beyond space and time. The name ‘Bowman’ - the user of a fundamental piece of human technology - is very deliberate. Especially as he represents a whole new development in the human evolutionary story, becoming the Star Child, a giant baby floating in space, looking down on the Earth. A whole new kind of being for a whole new world.

Science fiction is almost always set in a new or ‘secondary world’. J. R. R. Tolkien coined the term ‘secondary world’ to describe settings such as his Middle-Earth, worlds entirely created by the author to give a story a setting. Sometimes that secondary world is our world in the future; sometimes literally an entire other planet. You can think of a secondary world in two different ways: for some it’s a controlled thought experiment, a place of minimised variables in which theories can be safely tested. But you can also think of it as the product of imaginative exploration. Some look down on science fiction as mere ‘escapism’, but – trapped as we are in this forced labour camp of reality – perhaps, like imprisoned officers in the Second World War, it is our duty to escape. The secondary world offers us a place to escape to, entirely beyond the conventions and mundane strictures of the real world. Somewhere we can slip the surly bonds of Earth and imagine wholly new possibilities and kinds of being.

This is, ultimately, what spoke to me as a child, and what continues to speak to me in space travel and in science fiction. As in 2001, beneath the literal, mineral surface of the Moon there still lies a world of imagination. The naked-eye observations of the phases of the moon might have been the beginnings of astronomy, but they also represent wonder. This constant inconstancy, this strange companion; forever in sight, forever unreachable, always predictable, always changing. The ice-cream glow of the full moon; the thin, dim light of the crescent; the haunter of the night and the shepherd of dreams. Even in its scientific reality, there is credibility-straining weirdness. It can reach out across space to pull at our oceans in the great planetary breathing of tides; it is exactly the right size and distance from the Earth to perfectly cover the Sun in a solar eclipse.

The term for travelling beyond the gravitational pull of a planet is ‘escape’. Even with the signature of Richard Nixon embedded on its surface, the Moon is a symbol of the human imaginative capability that allows us to build a civilization and then to leave it. We escape the Earth to reach for the Moon.

For more pondering on the past and future of human technology and imagination, there’s always Jacob Bronowski and ‘The Ascent of Man’

“More recently, Elon Musk has taken to naming his rockets after spaceships from Iain M. Banks’ Culture novels”

When I noticed he was doing this, I realised that Elon Musk is not a Very Smart Boy™️.

Indeed good science fiction is not at all about science or engineering, but all about the "secondary world" you mention. It's about imagination. Doesn't have to be science, but plausible in its own "scientific" logic (contrary to fantasy stuff). That's what Iain M. Banks was so good at, and what Neal Stephenson is not so good at. As for the moon.... in itself it is of as little interest as the pebbles you brought in, if it wasn't for your imagination.