Books to fall asleep to (non-pejorative)

Rowan Davies: I finally wrestled Diarmaid MacCulloch’s Thomas Cromwell to the ground this month after a couple of false starts. Hilary Mantel and MacCulloch were researching Cromwell at the same time in the late noughties, and developed a close friendship while doing so. (This is ballast for my thesis that the pragmatic, adaptable and economically literate Cromwell was an appropriate hero for the anti-ideological age of Clinton, Blair and Obama.) Mantel published first with Wolf Hall in 2009, but MacCulloch managed to slip Thomas Cromwell (2018) in between Bring up the Bodies (2012) and The Mirror and the Light (2020), a run of events that transformed this eminent historian of Christianity into a best-selling non-fiction author.

Thomas Cromwell is catnip for the Wolf Hall devotee, albeit necessarily a little confrontational in places. Rationally, I knew that Cromwell got up to a lot of, er, crappy stuff (self-enrichment, torture, toadying, killing), but Mantel tends to let him off the hook (or perhaps shows us Cromwell letting himself off the hook - although I honestly think it’s more the former than the latter). MacCulloch, appropriately, is unsentimental and unsparing in the details.

Thomas Cromwell has gone straight into one of my favourite genres: books that I can read myself to sleep with. The boundaries of this category – which exists only in my head – are extremely well defined. The writing must be excellent; mangled sentences, repetition, stupidity and boring vocabulary keep me awake. The subject matter must be non-fiction (novels are too involving), and it must be something I’m genuinely interested in (I mean no shade here, but I personally do not care about gardening or the history of aviation). The narrative must be as un-pulsating as possible, for obvious sleepy reasons; I love Michael Lewis, but he’s for staying awake with, not going to sleep with. And the author must be a genuine subject expert, preferably an academic or someone who works in one of the less groovy think tanks. Journalists and professional writers tend to be far too good at telling a story, and that only makes me want to stay awake so that I can find out what happens next.

What I like is an extremely erudite, clever, informative-but-meandering drone delivered with real panache. My favourite book of this kind is Christopher Clark’s Iron Kingdom (an 800-page, 350-year history of Prussia), which includes sections on the Brandenburg education system that would send a caffeinated cocaine freak into a deep snooze. Richard Rhodes’s The Making of the Atomic Bomb is another absolute killer (hundreds of pages about electrons hitting foil sheets), as is Tony Judt’s Postwar (much, much more than you ever needed to know about the European Economic Community).

Thomas Cromwell contains multiple passages about Tudor ‘affinities’, the informal groupings of men-on-the-make who clustered around Court personalities. MacCulloch is, quite justifiably, keen to establish exactly who was in Cromwell’s affinity, and these passages – in which the movements of Mr (later Sir) Edward Squidlington are painstakingly traced over decades, from abbey to fishpond to New Year present to account book – are absolutely, perfectly boring.

Letterboxd Diary

What Tobias Sturt has enjoyed watching this month.

Bourne-ville

The Bourne Identity (2002), The Bourne Supremacy (2004), The Bourne Ultimatum (2007)

I was actually looking for The Matrix (1999) for a little January comfort watch and then discovered that it wasn’t available to stream anywhere so I settled on that other Gen X action stalwart, Jason Bourne.

At the time Bourne was heralded as a Bond for a new generation, with none of the blatant sexism, xenophobia or quippy amorality that Gen X found so queasy. Bourne had a serious German girlfriend, a begrudging facility with the beautifully choreographed and crunchy fight scenes, and knew that the intelligence services he once worked for were sinister and unreliable.

It’s that last point that really stood out on this rewatch. The films are solely about Jason Bourne’s relationship with the CIA he once served, and this severely limits the sequels. They keep having to go further up the chain of command to find ever-more-evil CIA chiefs for Bourne to hit with a rolled up magazine. Each subsequent film is a retread of the previous one, but with Albert Finney instead of Brian Cox, David Strathairn instead of Chris Cooper. We avoid the ludicrous threat escalator of Marvel films (I’m going to destroy you! I’m going to destroy the USA! I’m going to destroy the galaxy! I’m going to destroy THE MULTIVERSE!) But it also means that the films are only ever about Bourne and his vengeance.

More realistic stakes are also less idealistic ones, apparently. This super-spy isn’t capable of dispensing justice, serving their country or saving the world; he can only look after himself. Perhaps it’s this really that made Bourne the perfect action hero for Generation X: he was socially liberal and yet deeply individualistic.

Le Samourai (1967)

In which Alain Delon’s loner hitman screws up a job and finds himself on the run from the cops, the mob that hired him and, ultimately, himself.

It’s no less ludicrous than Bourne films, really, and I’m not sure I buy the porcelain Delon as a killing machine any more than the pug-nosed Matt Damon. But by golly, it’s beautiful. The opening sequence alone is worth the price of admission: a static shot of Delon smoking in bed in a darkened room as the credits roll over the top. At first you think the film is in black and white, until he finally moves and you really it’s just that his whole world is grey: a grey room, grey clothes, grey cigarette smoke. He is the only discernable thing in his world. And so, right from the beginning, you know what this man is like and can probably guess that he’s doomed.

Santosh (2024)

A Bourne antidote: a British/Indian film with a perfect Hollywood set up. Santosh is a young Indian woman living in a drab town far from the bright lights. When her cop husband dies suddenly in the line of duty, she discovers that she is allowed to take his job in lieu of a widow’s pension, and finds herself investigating the death of a young girl while under the wing of a rare senior female detective.

The film then proceeds to do something very un-Hollywood with the concept. Instead of telling a story about a counter-intuitively brilliant detective team fighting engrained misogyny, the film exposes a vein of brutal police corruption that provokes unpredictable responses from Santosh herself. (The film, which also touches on the status of Dalits and the self-serving behaviour of rural elites, still hasn’t been officially screened in India.)

One of things that stood out to me is how the film seems to deliberately protect Santosh herself from the threat of physical violence, and instead subjects her to moral violence. She is in a three-way fight between her desire to do a good job as a police officer, her desire to be accepted by her mentor and her fellow officers, and her basic humanity. Shahana Goswami plays this absolutely perfectly, simultaneously naive, hard, nervous, stern and troubled. We should warn you, though, that it’s incredibly depressing.

Mountainhead (2025)

Part of the job of satire – altogether now – is to comfort the afflicted as well as afflict the comfortable. In fact you could argue that is most of the job. Rude impersonations and clinical piss-taking don’t tend to change anyone’s behaviour, but they reassure the rest of us that we are not alone in finding things awful, ridiculous or frightening. Satire tells us that there are fellow humans who feel the same way we do: people we can trust, people with whom we might huddle and even organise; people alongside whom we could even seize power, thus becoming the objects of satire ourselves.

Jesse Armstrong’s directorial debut is a satire about four tech moguls who go on a retreat and, confronted with each other’s awfulness, lose their minds. It’s not telling us anything we don’t know: we know these people are awful. (Two of the characters are assumed to be avatars for Peter Thiel and Elon Musk; Steve Carrell is extremely good in the former role.) Part of how awful they are is that they insist on thrusting their awfulnesses into our faces every day through their apps. We know they’re over-schooled and undereducated, asocial and amoral, unloved and uncontrolled.

What Mountainhead does is reassure us that we’re right: they are awful. It gives us a space to laugh, with a ghastly sort of terror, at the men who have taken one of the greatest human inventions and turned it into a machine for producing misery, madness and money. And there are some good laughs and splendid jokes in Mountainhead. But sadly they start to diminish as the plot moves into gear.

Armstrong likes a dark realism in his satires. Part of the success of Succession (2018–23) was that the Roy family were realistic characters. The satire was still there, but as you got to know them – and to understand why they were like that – you started to feel some grudging sympathy for them (if not actual empathy). The satire bit harder and comforted the viewer a little more precisely because these were people, not thinly-veiled caricatures.

Because it has to establish a narrative and deliver plenty of laughs within a two-hour window, Mountainhead does not quite have the time to develop the characters enough. And the movement of the plot from character-based comedy to murderous farce perhaps needed a little more absurdism in it to help it take off. There is a moment in the film, in the middle of a murder attempt, when a bevy of lawyers are summoned to negotiate between the aspiring killers and the terrified victim. Sadly, we never get to see the drafting of the resulting contract. I would have liked to see that film: a film about the cringing minions, not just the monsters they tend to and facilitate (another thing Succession pulled off brilliantly with the ghastly Gerri, Hugo, Karolina and Karl.)

The Ice Storm (1997)

A case study in how a film can seem terribly adult and subtle when you’re in your twenties, and somewhat blunt and hysterical thirty years later. A group of affluenza-afflicted suburbanites in the early ‘70s treat Cosmopolitan and Playboy like instruction manuals (wife-swapping, self-actualisation, Valium, shop-lifting) while causing untold misery to themselves and everyone around them, particularly their kids.

We got kinda irritated by it on this rewatch and ended up mostly paying attention to the sets. It’s interesting to compare its echt suburban ‘70s interiors with those of The Holdovers (2023), which is rapidly becoming a Christmas staple in this house. The Holdovers takes place in a ‘70s that is not only a little bit ‘60s, but a little bit ‘40s and ‘50s too, and even a little bit 1890s in some places. Given that most people don’t throw out their furniture every ten years, The Holdovers feels like a more recognisable ‘70s. I do, though, want an awful lot of the furniture from The Ice Storm. Apart from the water bed. And the bowl of keys, obviously.

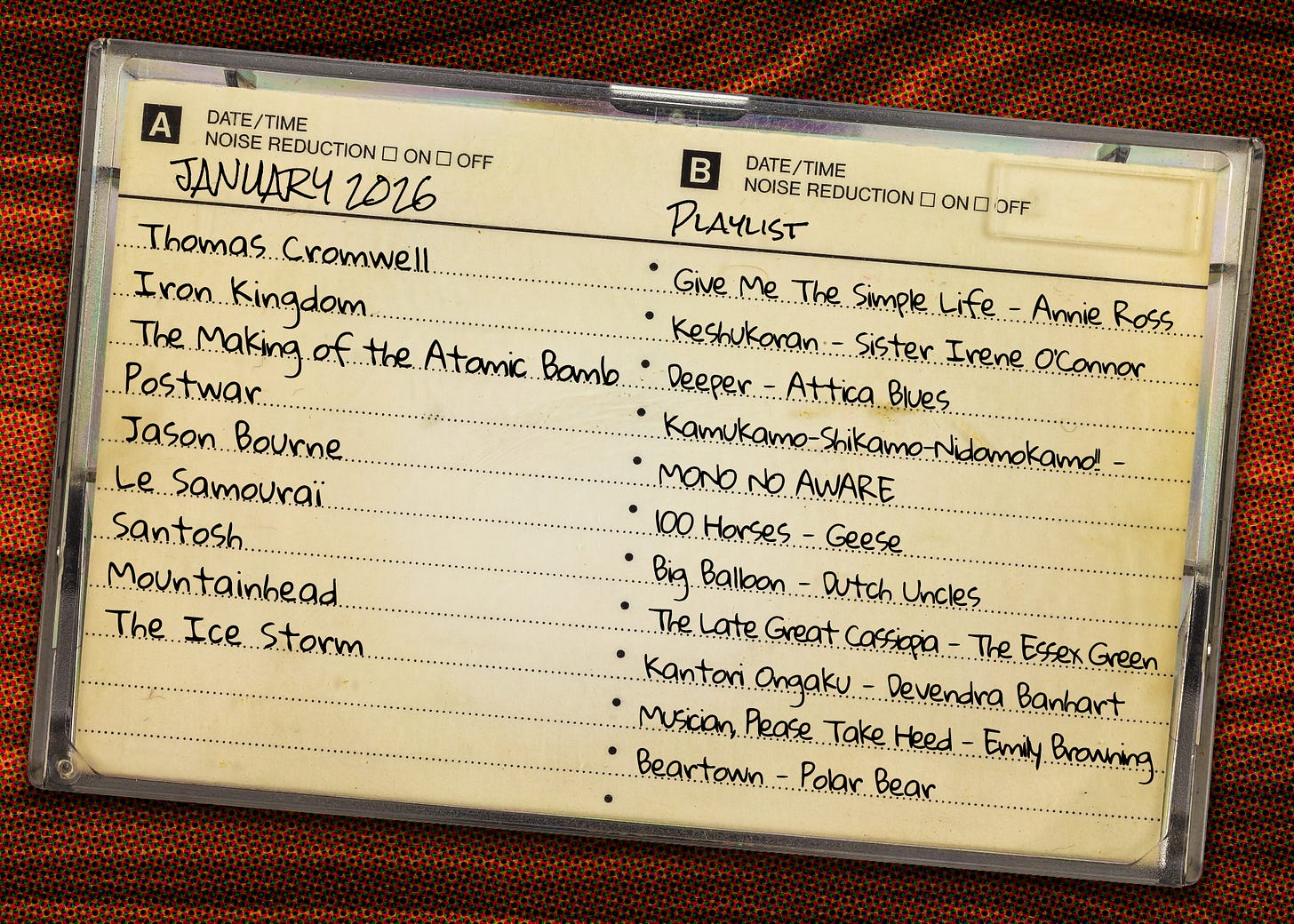

Playlist

Tobias Sturt: Here’s my favourite ten tracks for this month.

Give Me The Simple Life - Annie Ross, Gerry Mulligan Quartet. Starting January with good intentions of leading the simple life after all the Christmas indulgence.

Keshukoran - Sister Irene O’Connor. Sister O’Connor is Catholic nun who writes her own devotional music, produced and engineered by a fellow nun, Sister Marimil Lobregat.

Deeper - Attica Blues. Somehow January feels like a trip-hop sort of month: a little bit blue, a little bit woozy, a little bit unnerving.

Kamukamo-Shikamo-Nidomokamo!! - MONO NO AWARE. But perhaps we need to stop moping about and perk up a bit. Or a lot.

100 Horses - Geese. I’m old, so I’ve heard a lot of hip New York bands. At the beginning I kept expecting someone to shout ‘Blues Explosion!’ Then I thought David Byrne might join in. And then I wondered if it was The Strokes. But then, I like all those bands too.

Big Balloon - Dutch Uncles. I’ve heard a lot of Manchester bands in my time, too. This is a good one, a lovely mixture of muscular rhythm and soaring tune.

The Late Great Cassiopia - The Essex Green. Speaking of New York bands, here’s a nice piece of psychedelia-inflected rock.

Kantori Ongaku - Devendra Banhart. Ah, the twenty-first century Donovan. Well, I have a soft spot for the twentieth century Donovan n’all, so I am happy to have another one.

Musician, Please Take Heed - Emily Browning. I’m afraid I’m a Belle and Sebastian fan (a middle-aged indie white man? Really?), but I’m willing to admit that Stuart Murdoch’s whine can be an acquired taste.

Beartown - Polar Bear. Finally a little blue, woozy, unnerving circus march to accompany us into the dregs of winter.

You can find the whole playlist on Spotify, as usual:

For visions of history that are guaranteed to keep you awake, there’s always the genre that Rowan Davies has termed ‘macaron timeclash’:

McCulloch is one of my favourite historians, the more so for being able to write so well and engagingly about something I’m not all that interested in (the history of Christianity). I think I recognise what Rowan is describing here in a book I have on the go at the moment, Peter Wilson’s history of the Holy Roman Empire. There’s something very soothing about reading about Lothar the Flat’s defeat at the Battle of the White Pheasant in 1412 at bedtime. It drowns out Everything That’s Going On for a while, enabling sleep. The trouble is, it makes me want to look things up, or see if there’s a cheap copy of a biography of Gustavus Adolphus on amaz*n. And that lets ETGO back in. Ban phones. Lothar the Flat never needed one, after all.

I'm going to need your opinion on "Steal" on Prime Video. I quite liked it, and I didn't feel like there were glaring plot holes beyond the usual "how is it possible that you can fire machine guns at people in a confined space and somehow miss?" thing. But I'd be interested to know what you think!