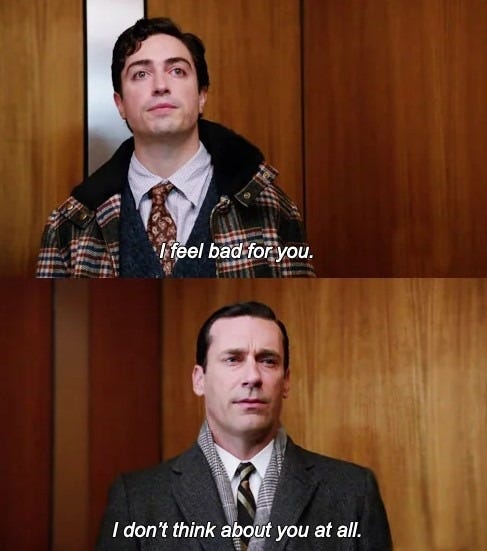

I don't think about you at all

There’s a famous dunk in Mad Men in which some young dweeb in a plaid coat (I don’t know who he is, because I’d stopped watching Mad Men by this point) says to Don Draper ‘I feel bad for you’ and Don Draper devastatingly replies ‘I don’t think about you at all.’ Zing!

When you’re young, this is a thermonuclear insult. The thing is, though, by the time you’ve reached middle age, it really should sound like sanity. Most of us aren’t thinking about most other people, most of the time. This rubric explains 99% of petty social hurts: birthdays that get forgotten, parties you don’t get invited to, Christmas cards that never arrive… why not assume that none of this stuff is intentional? ‘They’re probably not thinking about me’ is a life hack, not an opening of hostilities.

I’ve been thinking about this recently because I’ve been spending time with large groups of people over Christmas and New Year, and — as an introvert — socialising with large groups of people almost always makes me deeply uncomfortable. And when I can’t get comfortable, I have to guard against bad self-soothing strategies (getting drunk, falling silent, sulking), and coming up with wrong explanations of why I’m feeling uncomfortable (‘that person is unpleasant’, ‘I’m bored’, ‘everyone hates me’, ‘this is a terrible party’). I say I have to guard against them; I don’t say that I always succeed, which is why I am sometimes functionally indistinguishable from a grouchy, self-obsessed bastard. Or a drunk person.

If you think that saying things like ‘as an introvert’ is pretty much like saying ‘as a Capricorn’, I do understand your reservations. Introversion/extraversion is not, of course, a well-evidenced medical condition. It is a proposition, a theory about personalities; it derives from Jung, but then, what doesn’t? Jung didn’t intend that everyone should start labelling themselves ‘introverts’ or ‘extraverts’; he thought most people had elements of both, which seems true on a common-sense level. From my lofty position as someone who has a Level 3 Certificate in Counselling, I’m going to go ahead and say that if you’ve read brief descriptions of introversion and extraversion and found that neither particularly resonated with you, you can probably tick ‘N/A’ and move on with your life.

Any value in these personality theories lies in the extent to which individuals use them as constructive tools for understanding themselves and making positive changes in their own behaviour. (In this, you might say, they are exactly the same as astrology.) All I know is that around a decade ago, I saw a Twitter conversation about Susan Cain’s book Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking (2012), and the value of the introversion/extraversion model felt suddenly, startlingly clear.

I’ve never read Cain’s book. I don’t read self-help books, as a rule, and the Wikipedia summary linked above makes it sound a bit insufferable. (If it’s true that she claimed that introversion should be the next big civil rights cause, then I can only say ‘WTF’.) But the premise of the Twitter conversation was more specific: the idea that the difference between introverts and extraverts can be explained using the metaphor of a social ‘battery’. For introverts, this battery — the amount of available energy for face-to-face interactions with other people — is depleted by spending time with other people, especially in large groups, and can be ‘recharged’ only by solitude.

Until I read this, I’d always assumed that I wasn’t an introvert because I’m not shy. I’m pretty self-confident, not notably self-effacing, and sociable when I want to be. The social battery metaphor explains why someone like me might nevertheless frequently find it impossible to socialise. Introverts can be social; they can happily give a presentation at a conference or go to the pub. What makes you an introvert is when, after doing these things, you have an immensely strong, almost sub-cognitive need to sit by yourself in a quiet room for a few hours. The bigger the gathering, or the harder you have to work (eg getting to know new people), the quicker your battery runs down. If you’re in a situation in which you cannot recharge, the problems begin (see above: withdrawal, substance abuse, sulking, etc.)

When I saw this ‘social battery’ metaphor, a lot of pieces suddenly clicked into place, and I saw a whole bunch of slightly painful stuff in a different light. For instance: it made sense of why, while taking my A Levels, every working day for two years I bought a hurried sandwich in the huge, noisy canteen and then furtively took it to a toilet cubicle, where I would lock myself in and read a book for an hour until my next lecture. I’d felt bad about that for decades; it was objectively very weird (not to mention incredibly unhygienic) and I couldn’t work out why the young me had done something so strangely, self-defeatingly tragic. Why hadn’t I gone to the library, or a park, for crying out loud? Well: because other people were in the library and the park.

It also made sense of the fact that despite finding it easy to give public speeches and appear as a media spokesperson on TV, I am almost physically unable to ‘network’, even though it’s a critical part of my job -- another thing I’d been ashamed of for years, because it affected my professional competence. (The impossibility of networking, for me, is quite hard to describe. I don’t just mean ‘it’s difficult’ or ‘I don’t like it.’ It’s more like that feeling of total paralysis that you sometimes get when you’re dreaming.)

For decades, I’d thought of these things — and literally hundreds of similar incidents, big and small — as evidence that I was a deeply awkward and perhaps slightly broken person. This assumption was buttressed by the fact that my whole life, I’ve been relatively unpopular. I’ve always had some good friends, and believe me I’m extremely thankful for that. But I’ve never more than a handful at any one time, and often appreciably fewer than other people around me.

What’s wrong with that, you might say: if you’re an introvert, surely limited popularity is the goal. Which is kind of true, except that for a long time I didn’t understand why it was happening. I didn’t realise it was the logical outcome of my own core preference for limited socialising, a preference that turns out to motivate me more strongly than my (also-existing) enjoyment of friendship. Instead, I just thought I must be repellent in some mysterious way that nobody could explain.

Understanding ideas about introversion allowed me to shift the explanation. I wasn’t repelling people; most people probably felt neutral-to-warm about me. But making friends is an action, a process. You cannot just loll about, reading books and eating pies in total silence, and expect fully-formed friends to fall into your lap. I had subconsciously chosen to not do the things that are necessary to the active formation of friendships.

Decades ago I had a conversation with a friend during which she said something that I didn’t really understand, but which I’ve never forgotten. It had the force of something deeply true, and people don’t say deeply true things very often. We were talking about why she attracted roughly ten times more romantic interest from men than I did, despite (we both agreed) me being better looking. (I’m not trying to be all Samantha Brick about this. All the evidence demonstrated conclusively that my friend was much, much more attractive than I was. But I had a better face, and I thought that meant I was owed… something. Men’s attention.)

After nibbling around the edges of the topic for a while, she said — in a tone that suggested it was obvious, and she really shouldn’t have needed to spell it out — ‘It’s because I want it more than you do.’ She was talking about male attention, but she had loads of platonic friends too, and the principle is the same. She was honestly identifying the motivation that caused her to expend so much social energy: to stay upbeat and charismatic when a party was flagging, to take a lively and consistent interest in people, to be endlessly inventive in finding ways to make people laugh. All of this came at a cost to her, but it was a price worth paying to get the things she needed. Everywhere, all the time, people are doing costly things because they are sufficiently motivated by the outcomes.

As I’ve got older, and most particularly since I recognised my introversion, I’ve let myself off the hook about most of this stuff. I literally could not cope with a large friendship group, so it’s genuinely no skin off my nose that I don’t have one. And anyway, the absence of active friendship is not the same thing as hostility. After all, I’m not-friends with a lot of people towards whom I feel perfectly warm, people I’d happily give a lift to or buy a drink for. I’ve every reason to think they feel the same way about me. We just don’t proactively arrange to see each other, and that’s fine, because if we did I’d probably try to get out of it at the last minute, and then they would really start to hate me.

Letting yourself off the hook, making sense of difficult incidents, enabling a sense of chill: these are all good, constructive things that this kind of self-labelling can give you. What occurred to me over Christmas, when I was drawing attention to myself by being quiet and anxious, is that there’s also a raging egotism in introversion, an egotism that is both furtive and highly neurotic, and that I probably need to keep a check on.

I said above that I’m happy to give a speech but I’m not happy to network afterwards, and I said that this is because I need to get away and be on my own. That’s true; I really do need to get away and be on my own after an hour or so in a large gathering of people, and I have many strategies for doing so. (Show me an introvert and I’ll show you someone who knows where the toilets are.) But it’s also kind of convenient, isn’t it, that I’m happy with giving a speech — ie, the bit where I’m the centre of attention and I get to control what’s happening — and I’m unhappy with the bit I can’t control, the bit where I have to negotiate with the fleshy demands of other people’s wants and needs and interests and judgements; the bit where I come face-to-face with the concrete evidence that I am not at the centre of most people’s worlds.

There’s an undeniable correlation between situations in which introverts feel comfortable — intimate conversations, small groups of close friends — and situations in which the introvert gets to hold forth and be constantly affirmed. (Apparently lots of introverts like writing, which, again...) I don’t feel particularly bad about this; I rather like egotists. Some of my best friends, etc. But this egotism does explain why introverts, and all the other anxious neurotics who carry their personality types on a placard whenever they enter a room, have a tendency to expect everyone else but them to alter their behaviour.

This is where ‘they’re just not thinking about me, and that’s OK’ comes in useful. Maybe it’s because I spend a lot of time hanging around on internet forums (where neurotics and introverts tend to be over-represented), but I can’t help thinking that introverts everywhere need to recognise that socially adept people don’t owe us extraordinary consideration. Why didn’t the cluster of mums at the school gate break off from their conversation to say hello to you? Because they weren’t thinking about you! Why are you only finding out about your colleagues’ after-work socialising from the Facebook photos? Because they weren’t thinking about you! They haven’t ignored you, or left you out, or deliberately been unkind. They haven’t painstakingly constructed a ‘clique’ (or, as normal people call it, a friendship group) and barred you from it. They’re just not thinking about you at all, because they’re far too busy thinking about themselves. Just like you are.

Of course, good girls should be seen and not heard anyway.

Love the "locked toilet with a book" part. Some people really can't understand the haven that is. I once (many, many, many years ago) had a discussion with P. on that (whom you know). She just didn't understand how you can spend that much time alone on the toilet. The resourcing of the social battery would have been a good analogy, if only I had known....

I love this. As an introvert myself, much of what you say feels like a ‘light bulb’ moment. And a relief to understand myself more. Oh, and what a surprise, I’m a writer…x