Gangster cats and kung fu dogs

Don’t move or the bunny gets it

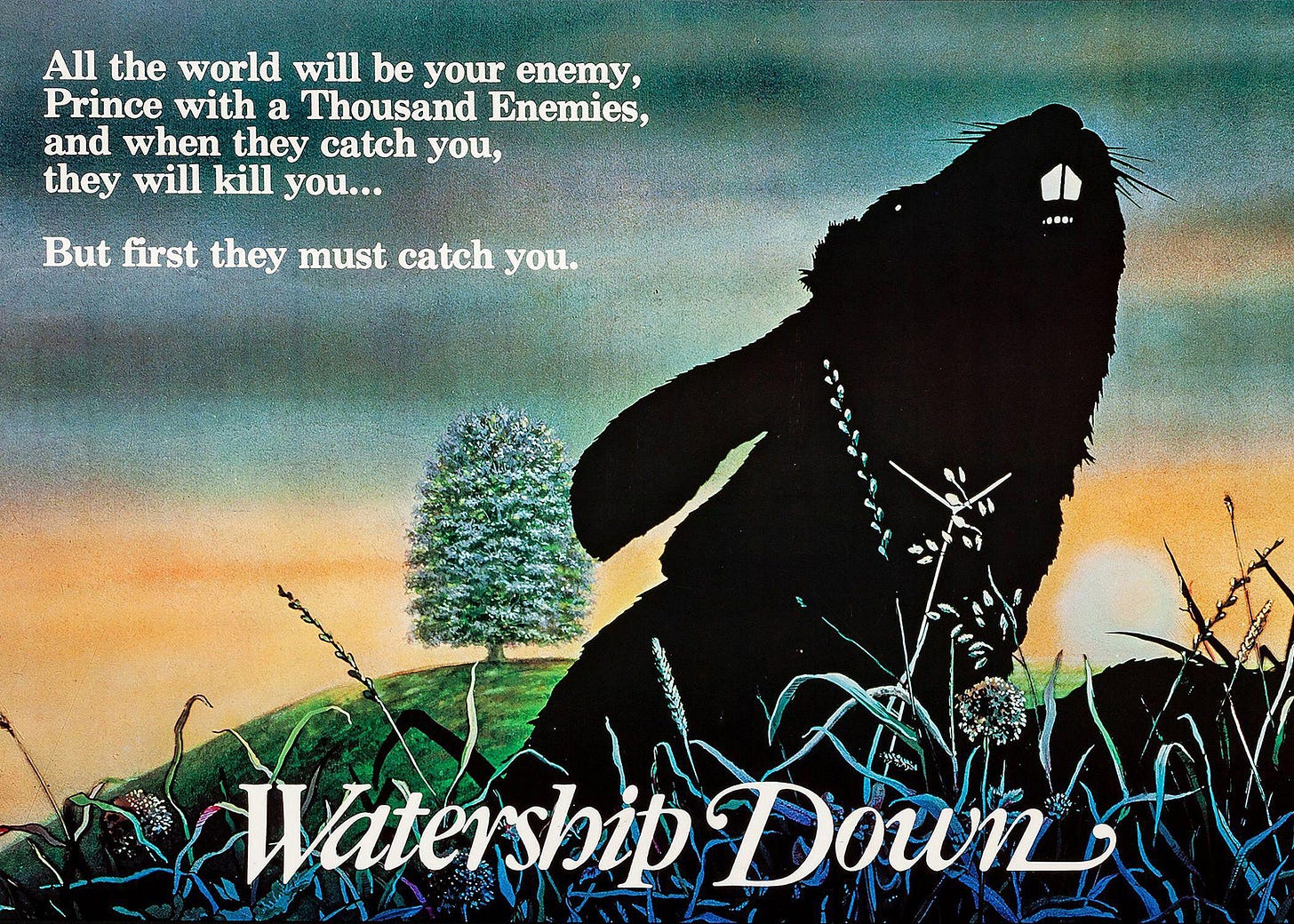

“All the world will be your enemy, prince with a thousand enemies.”

Lord Frith

One-Upmanship author Stephen Potter once advised that the perfect gift to undermine a young child just getting into spaceships and zap guns would be a story book about a hedgehog who wears a watch and chain. It happened to me. In my peak Star Wars / Dr Who phase I was given a book called The Wishing Chair, in which a pair of Edwardian siblings have all sorts of adventures with the help of a magic chair. I muttered thank you, blushed, and hid it. So it would seem deliciously cruel to take an eight year old interested in Daleks to see a cartoon film about rabbits; but that is exactly what my sister did with me.

I was always going to be receptive to Watership Down to some degree; children are able to pay instant attention to almost anything in cartoon form. (The question remains, of course, whether any given cartoon will breach the child’s remaining critical ramparts. Scooby-Doo, for instance, was the real deal, while Scrappy-Doo was totally phoney. And don’t get me started on Goober and the Ghost Chasers.) I had also seen the video for Bright Eyes, the rather dreary Mike Batt/Art Garfunkel hit song from the film, so I already knew the rabbits in this cartoon were not drainpipe-limbed wiseasses à la Bugs Bunny, cocking a snook at mortality with the wave of a carrot. These rabbits were seriously drawn, and – if you overlooked their dewy eyes and worried expressions – were relatively realistic. If they were hit by a frying pan, they would not assume the shape of a frying pan. If they fell from a great height onto a distant canyon floor, they would not land with a puff of cartoon dust. But all of this was OK with eight-year-old me. Because I knew these rabbits could talk.

People our age were raised by talking animals. From the cradle, the Gen X child was surrounded by gangster cats and kung fu dogs. There were also lambchop sock puppets, Kermits, Cookie Monsters, Bagpusses, Banana Splits, and bears riding invisible motorcycles. It was from these Aesopian forms, through comics and TV, that we began to learn how to be human – to rehearse what we might become, and take steps to avoid what we didn’t want to be. If Top Cat exemplified confidence and Big Bird was a lesson in vulnerability, then Sooty was a sinister controller, Orinoco a timorous glutton, and Bungle a passive-aggressive nay-sayer in an apron. We were never going to listen to our parents, but we paid careful attention to an experientially fallible bear with a hard stare and a sandwich under his hat.

Against the talking animals that lurked in the hedgerows of our imagination, real animals were a bit disappointing. If, like me, you grew up without pets because your parents thought they were untidy, actual fauna was at a remove. David Attenborough’s TV wildebeest ran about, gave birth and got chased and eaten, but they taught us few relevant life lessons. Outside in the Welsh semi-countryside where I grew up there were no exciting animals - no antelopes, no elephants. Disappointingly, no baboons. Only rabbits. Lots of them. And they didn’t speak. They were surrounded by turds, had weird baggy cheeks and blank sideways eyes, and I was warned not to go near them because they probably had myxomatosis.

The legendary disease that tore through the British bunny population in the ‘50s and ‘60s became a part of our island folklore, and joined with rabies in the popular imagination to inform a widespread belief that the countryside was hedged about with danger, dirt and disease. In my parents’ copy of Thelwell Country (1959) by Norman Thelwell, that great satirist of the mid-20th-century English countryside, there’s a two-part drawing showing a countryman losing his cap while pelting downhill to escape a pack of ravening foxes, only to find that his cottage has been taken over by angry Hitchcockian birds. The caption reads: ‘As a result of myxomatosis, foxes are becoming as savage as wolves… and birds, owing to the Protection of Birds Act, are losing their fear of man.’ For me, this animal unpredictability tallied with parental warnings about the lethality of the great outdoors. If you eat a strange berry you will die. If you don’t wash your hands after playing outside you will get a tummy ache and die. Cows will chase you, farm dogs will bite you and you will die. Flowers and plants not from an orderly garden are poisonous weeds. And don’t ever, ever walk behind a horse; it will kick you in the head, and that will be that.

And so, weighted down with such socio-cultural baggage, justifiably afraid of the countryside, not knowing my henbane from my purple loosestrife, and with scant interest in rabbits, I was taken to see Watership Down some time early in 1979.

“Is there something about death you don’t want children to know about?

It’s going to happen to us all.”

Martin Rosen to Swedish censors

The childhood trip to see Watership Down at the cinema has become part of the Gen X cultural mythology: at a tender age we were taken out for a treat to see a nice cartoon about rabbits, only to bear witness to a bunny Passchendaele. The film, written and produced/directed by Martin Rosen and adapted from Richard Adams’s 1972 bestseller, traumatised an entire generation of people who, in middle age, now surf the internet when they’re supposed to be working, looking for pictures of things that frightened them as children.

On its release in 1978 the film was given a U rating – ‘suitable for all the family’ – because… well, because it was a cartoon about rabbits. The ‘Parental Guidance’ rating did not apply in British cinemas before 1982, and it took decades of parental complaint for the British Board of Film Classification to finally confer PG status in 2022, possibly hastened by the outcry that followed Channel 5 beaming the film into horrified living rooms on Easter Sunday in 2016. The programmers must have enjoyed themselves, because they did it again on Easter Sunday the following year.

Martin Rosen didn't intend to make a film to upset kids; he didn’t intend to make a film for kids at all, even though Adams’s novel had won both the Carnegie Medal and the Guardian Children's Fiction Prize in 1973. Interviewed by The Independent on the 40th anniversary of the film’s release, Rosen emphasised that he had wanted to preserve on screen the robust seriousness of the novel, which had initially struggled to find a publisher because it was deemed too childish for adults and too grown-up for children. Of the famously bleak poster image for the film, he said: ‘I reckoned a mother with a sensitive child would see a rabbit in a snare with blood coming out its mouth and reckon, well maybe this isn’t for Charlie.’

Rosen’s rabbits do not have waistcoats and watches. They are presented in cartoon verité: hopping and nibbling like the real thing, tearing each other’s ears to shreds, frothing at the mouth and bloodily expiring. What Rosen presents, in a plain and flattish animation style, is a straightforward tale of conflict and survival at dandelion level in an often dark and unforgiving English countryside. This is the bitter reality of hedgerow strife, roiling away beneath and beyond human sight and understanding. And while the timorous creatures whose adventures we follow do talk, they speak the Queen’s English in the no-nonsense tones of Great Escapees tunnelling out from the Stalag Luft 3 shower block. Spoilers ahoy.

A young runt rabbit named Fiver (Richard Briers), blessed and cursed with foresight, convinces his brother Hazel (John Hurt) to leave their Berkshire warren following a vision of impending death. The vision is prompted by the discovery of a man thing: a sign, which they can’t read, announcing suburban development coming to their field. After their complacent chief rabbit (Ralph Richardson) refuses to listen, the brothers slip away with a few friends, escaping dogs, rats, hawks and the tough police rabbits of the Owsla to arrive at a luxurious new warren full of carrots, whose rabbits (led by Denholm Eliot) are blandly welcoming, but evasive and sad.

Finding that the warren is surrounded by snares and that its inhabitants fully accept that they are being fattened for human dinners, Hazel’s group flees to the high ground of Watership Down where they can see what’s coming and live unmolested so long as they can recruit some does, the only female having been snatched by a predator en route. Learning from survivor Captain Holly (John Bennett) that the home warren has indeed been destroyed and that Fiver was right all along, Hazel plots the hutchbreak of a bunch of pet rabbits on a nearby farm, but falls foul of a large expansionist warren, Efrafa, governed with an iron claw by a dictator rabbit named General Woundwort (Harry Andrews). Hazel’s henchrabbit, Bigwig (Michael Graham Cox), infiltrates Efrafa and orchestrates the breakout of Hyzenthlay (Hannah Gordon) and her sister does with the help of injured seagull Keehar (Zero Mostel). The General’s superior forces attack Watership Down, only to be defeated by a combination of a vicious farm dog and their own fears, which send them into a helpless state of rabbit terror known as tharn. In the final reel, Prince El-ahrairah (Joss Ackland), the Rama-like trickster proto-rabbit of myth, summons the elderly Hazel, who has enjoyed a long and peaceful life, to join his spectral Owsla.

And as their smoky forms leaped through the cartoon sky, the tears rolled down my-eight-year-old face.

“Not my rabbits.”

Richard Adams

Some contemporary reviewers were harsh, finding the animation bland and unimaginative, and the story too literal. Others commended the film’s seriousness and lack of sentimentality. It reeled in those like my sister who had read and loved the book, and sent kids like me away to read it later in life. And it did well enough at the box office for The Goodies to take a pop at it. In February 1980, in an episode entitled Animals – which is today a bit of mirthless watch – Tim, Graeme and Bill tackle the contemporary hot topic of animal rights and end up hopping about in rabbit costumes to the sound of Bright Eyes amid gales of canned laughter.

Rosen’s adaptation necessarily simplifies the story for screen and omits much of the heft of the book, including the lengthy passages of carefully detailed ecological scene-setting - all that henbane and purple loosestrife. Richard Adams himself, having written a novel that shifted a million copies within just two years of its publication, could afford to be sniffy about it. ‘I couldn’t like it because it bore no relationship to my original work at all,’ he growled to Structo magazine in 2011.

But there, unspooling in front of me in the dark of the Theatr Clwyd cinema in 1979, was the terrifying countryside I’d been warned about. In Rosen’s sinister cartoon downland, the occasional bright sun merely served to hide a swooping hawk. Every bush concealed a snare; every dog was a slavering tyrannosaur; every berry looked like Deadly Nightshade. These instantly accessible talking rabbits were speaking directly to me, communicating their fraught existence in urgent tones leavened with gruff doses of war-film gallows humour. Knowing little about animation, and having forced himself into the director’s chair after sacking legendary American animator John Hubley for working on a side project, Rosen concentrated on the acting, coaxing thoughtful, nuanced voice performances from some of the finest actors available, who took it all very seriously, humanising the rabbit and rabbitising the human. Denholm Eliot, within the space of a few brief lines, fills the weary-looking Cowslip with charm, duplicity, ennui, resignation, distaste and deep existential melancholy. And this, remember, is a RABBIT.

These were not the passive creatures of my neighbourhood fields, sitting about waiting to be chased and caught, skinned and cooked. These were small, hard done-by, irascible creatures with a fervent desire to be left alone. Just like me.

I read the novel when I was a bit older. Its world-building drew me in, with its Tolkeinish rabbit-language and storytelling, and the reverse-epic sense that six months and a few square miles is a whole universe of time and space to a rabbit. Over the years book-plus-film seem to merge to form a kind of Greater Watership Down, thrusting a hefty paw into different cultural worlds: postwar eco-consciousness, the great playpen of animated cinema, and the 20th-century experience of global trauma. Richard Adams was an active and eloquent environmentalist, and would more explicitly address the subject of animal rights in Plague Dogs (1977), a tale of two hounds on the run from laboratory experiments. His rabbits’ fight for survival in a threatened and disappearing natural environment tapped into the growing ecological anxieties of the times, coming ten years after Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), and shortly before Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation (1975) and James Lovelock’s Gaia (1979). And as the rabbits teeter between life and death, Rosen’s film balances awkwardly between the great interwar Disney colourscapes and the renaissance of animated cinema in the 80s and 90s by Ghibli, Pixar, and Disney in its Lion King era.

But although the screenplay cracks along with some of the pace and language of a war film, both Rosen and Adams were keen to insist that it wasn’t. Despite admitting in his autobiography that Hazel and Bigwig were based on officers he had known in the Royal Army Service Corps, Adams was resistant to the hot take that Watership Down – with its secret police, poison gas and refugees – was an allegory for the horrors of the 20th century. It was, he always maintained, just a story made up to entertain his daughters on the drive to school. The warrens were not trenches; tharn was not shell-shock; the rabbits were not fighting fascism, in exactly the same way that Frodo and Sam weren’t.

And yet, as novel and film succeed in imbuing small and insignificant things with great and universal weight and importance, it’s tempting to draw larger parallels. As tiny creatures forever on the verge of death while in search of a peaceful existence, these rabbits seem somehow very familiar. Although I don’t see long ears when I look in the mirror, I did read the novel, again and again, and today I remain – along with many others – somewhere in the warren. Perhaps, for the Gen Xer, Watership Down provides a kind of reset, after years of ironic posturing, complex meta-narratives and Matrix shennanigans, to a simpler mode of storytelling, following vulnerable and unremarkable creatures as they outrun and outwit their enemies to save themselves. Perhaps by offering a reminder of the perils faced by an earlier generation, these thwarted, pugnacious bunnies can help us to face our current thousand enemies without going completely tharn.

The link between children and animals as outsiders in the adult world is well exemplified in Lucy M. Boston’s ‘A Stranger at Green Knowe

Is Horror at 37,000 feet the one where William Shatner is defenestrated from a plane?

I remember there used to be a notoriety about certain films and their effect on certain people, which I guess is why Channel 5 had fun beaming the bloodied bunnies into living rooms during those two Easters.

When I was very young on a family holiday in Torquay there was a frisson of anticipation about the hotel (which had a television room) because Psycho was about to be screened on TV for I think the very first time. I don’t remember watching it though. On another holiday (Anglesey) I recall my parents and sister staying up to watch Quatermass and the Pit, which I glimpsed from under my bed covers. Every time I looked out it was either hornéd aliens or a giant flaming devil. Not much sleep that night.

“The film, written and produced/directed by Martin Rosen and adapted from Richard Adams’s 1972 bestseller, traumatised an entire generation of people who, in middle age, now surf the internet when they’re supposed to be working, looking for pictures of things that frightened them as children.”

This is so accurate it made me laugh out loud. I watched this on my own at around the age of five in my grandparents’ living room by dint of them having acquired some magical precursor of streaming services called “Cinematel” via Radio Rentals. It remains singularly the most traumatising event of my childhood despite having a father who regularly worked back shifts and would therefore watch entirely inappropriate films while I was in the vicinity (Horror at 37,000 Feet, aged 7, The Fury with the frantically spinning woman expelling blood from her fingertips all over a beige hotel room, aged 12) Although, thinking about it, we all sat down to watch Jaws as a family when I was around 7 or 8 so attitudes towards children’s cinematic experience were obviously a bit different.

Anyway, “Watership Down” scarred me for many years and I didn’t go anywhere near it again until I was 17, where I discovered a deep love for it. I’ve watched it many times since and it never fails to make me cry. It’s as if things which scare us or upset us as children (and I’m talking about films and books here rather than actual trauma) are somehow bound into our psyche. I often wonder if these experiences are all part of why I love the horror genre so much - I know I can feel these strong emotions of dread and anxiety in the moment but switch off the screen and everything is fine.