We were raised by Puffins. With three TV channels and no internet, for long stretches of our lives reading was the best (and sometimes, the only) way to pass the time. Here we return to the books that made us and analyse what makes them great.

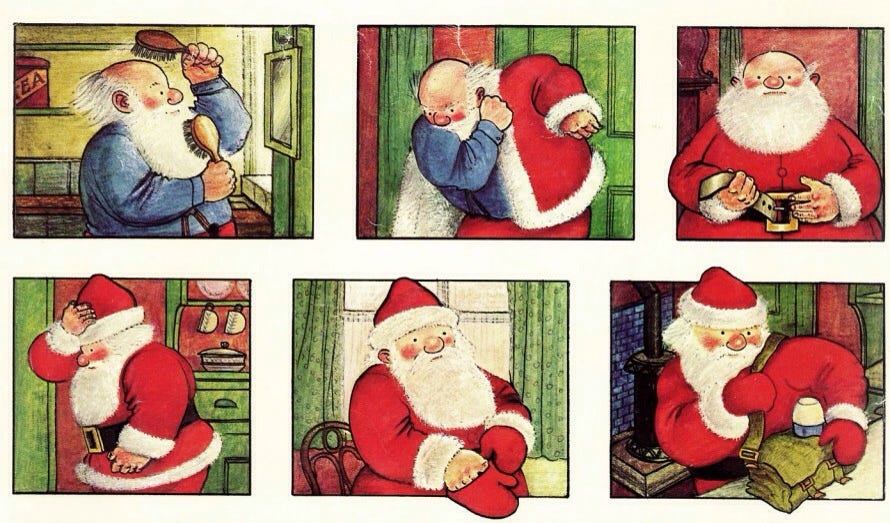

It’s bloomin’ Christmas Eve again. Father Christmas wakes up in his terraced two-up-two-down, makes breakfast, goes to the loo, feeds the animals and loads up the sleigh. Then it’s ‘good bye cat’ and ‘good bye dog’, and he’s off into the bloomin’ weather to do his rounds. On through the night he slogs, squeezing down chimneys, stopping for a sandwich between chimney pots, and bumping into a milkman. Finally it’s all done and he can go home, make his Christmas lunch, open his presents (Cognac! Good old Fred) and go back to bed.

Down the chimney

Father Christmas isn’t Raymond Briggs’s best known Christmas book; thanks to the famous Channel 4/David Bowie (??) animated movie, that would be The Snowman (1978). But Father Christmas came first. (And anyway, Briggs himself always said that The Snowman wasn’t supposed to be particularly Christmassy.)

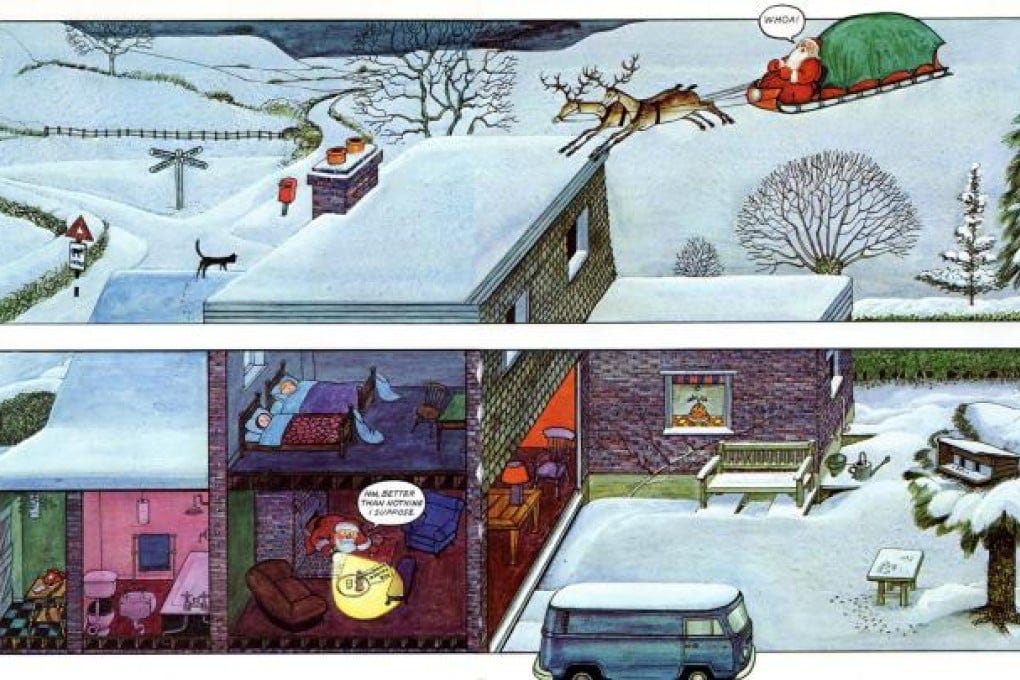

It inaugurated his great innovation: the use of comic book layouts in a picture book. This approach enabled Briggs to pack in more story. It also meant he could make full use of visual storytelling, building the narrative frame-by-frame where necessary. He does this so well that the text becomes additive rather than explanatory, a bravura technical achievement that culminated in the entirely wordless Snowman.

Not that Father Christmas has a dramatic story arc: it’s simply the events of one Christmas Eve told from Father Christmas’s point of view. And this isn’t the moral and mysterious Christmas Eve of A Christmas Carol (1843), or the wondrous and whizzy Christmas Eve of The Polar Express (2004). It is a realistic, hard-working night-in-the-life of a realistic and hard-working Father Christmas: one who swears at the rain, puzzles over how to get into a caravan, and nods off at the reins of his sleigh.

The simplicity and directness of this vision feels extraordinarily brave. To take something so straightforward and plotless and make it work required Briggs to place a great deal of trust in his own talent. He was, of course, entirely right to do so. He was a truly brilliant illustrator, marrying a cartoonist’s eye for character — all dynamism and economy — with exacting, accurate details in the backgrounds.

The specificity of the detail is where Briggs shows that as well as knowing and trusting his own talent, he also knows and trusts his audience. Small children live in a small world; small matters such as household brand logos — mysterious, impenetrable, laden with occult meanings — receive the full focus of their attention. The settings in Father Christmas are beautifully specific. The big man’s house is full of recognisable branded goods (a box of Corn Flakes for breakfast, an empty ‘Uxo’ tin for his sandwiches). When he flies over the Houses of Parliament and Buckingham Palace they are architecturally accurate, greebled about with inky crenellations. There is even, on one spread, a legible fingerpost that precisely places one house as being somewhere on Underhill Lane at the foot of Ditchling Beacon under the South Downs, not far from Raymond Briggs’s own house.

This is just one way in which Briggs uses familiar tools, forms and settings to reveal the enchantment of the everyday. He uses coloured pencils a lot — like those Caran d’Ache pencils you might get for Christmas — and they give the book a friendly beauty, full of bright colours and soft details. And he composes brilliant cut-throughs; houses are opened up to show Father Christmas worming his way down chimneys past stuffed attics and sleeping children, and emerging into sitting rooms lit by the soft light of Christmas trees.

The kind of pencils you might have at home; a comic layout like The Beano; a story set in recognisable homes. The everyday is exploded: hidden spaces are made visible, reality is reconfigured, and the secret workings of the world are revealed.

Among the gutters

As well as revealing the enchantment of the everyday Father Christmas also injects magic into the humdrum, capturing the way a child’s world is made (even more) mysterious and wonderful by the season.

Briggs’s comic book format uses very wide gutters (the white spaces between illustration panels). Gutters play an interesting role in comics. They serve to contain the imaginative space of the story, isolating the specific moments of the visuals from each other. They are also, however, a magical imaginative space, in which time and space become flexible, so that panels can be both sequential and singular. (In this way they are different from page turns, which are definite endings and reveals, and are the traditional locations of twists and cliff-hangers.)

Gutters are, literally, liminal spaces, defined by and outside the lines. What’s interesting is that Father Christmas constantly intrudes into them. Things — legs and arms, the sleigh, bits of scenery, speech bubbles — are forever poking out of the frames into the snowy white gutters. The story is escaping the confines of the book; the world of the imagination is irrupting into the world of the reader.

This is appropriate in a story about Father Christmas, an apparently fictional character who nevertheless manages to leave a delightfully tactile and splendidly real stocking on the end of your bed every Christmas morning. And it is appropriate to Christmas, the season in which we take ordinary trees, dull suburban cul-de-sacs and humdrum high streets and turn them into objects of wonder. We literalise friendship and love in the form of presents; we dramatise community and conviviality in feasting and celebration. We take the physical and make it mystical, take the emotional and make it physical.

Part of the joy of Christmas is that it suggests this enchantment is there all the time, just out of view. This is where Briggs’s specificity collides delightfully with the subject matter. By depicting a recognisable and familiar world, and making Father Christmas himself a recognisable and familiar grumpy old man, he is insisting on this most mysterious quotidian magic.

Across the rooftops

Apart from a few interludes (an igloo, a lighthouse), Father Christmas takes place in Britain. In southern Britain to be precise: in and around London and Sussex. Even Father Christmas’s house — which should be somewhere far away, judging by the flight times — is a recognisably British terraced house. This is because it was modelled on Briggs’s parents’ house; that’s his milkman father who bumps into Father Christmas in the early hours of Christmas morning. And that’s an electric milk float that his father is driving, a distinctly British vehicle.

And this book isn’t called Santa Claus; it’s called Father Christmas. Santa Claus is an invention of the Dutch heritage of New Amsterdam, and is more recent than Father Christmas (or, as Ben Jonson rather splendidly named him, ‘Captain Gregory Christmas’). This latter fellow was once associated with a more adult vision of Christmas, full of feasting and foolery. He was crowned with holly, as often dressed in green as in red, and brought beer and song rather than presents.

Raymond Briggs’s muse isn’t quite Captain Gregory Christmas, but he isn’t quite Santa Claus either. He’s a recognisably British character, and not just because he’s mostly landing on roofs in southeast England. The book is a little memento of a time when British and American culture wasn’t quite as intertwined as it is now; when Bonfire Night was more important than Halloween, and when none of us knew what a ‘Black Friday’ was.

This is not to make a tedious Facebook point. I’m not saying life was necessarily better and more pure back in the days of power cuts and Fingerbobs and open-access landfill sites. I’m just pointing out that there was a time in Britain, not that long ago, when ‘Santa Claus’ was not the biggest name in nocturnal present-delivery logistics. When I was a child in the ‘70s, it was Father Christmas we visited in Hamleys every year, Father Christmas to whom we wrote letters, and Father Christmas who left me a copy of Father Christmas when he visited my house on Christmas Eve, 1973. It had not been a cheerful year in Britain. As well as the Cod War and strikes and IRA bombings, the oil shock that followed the Yom Kippur War resulted in mandatory measures to conserve petrol and electricity.

Father Christmas, inspired by Briggs’s father’s own experiences as a milkman, is a fully recognisable British working man of the period, begrudging and swearing his way through the night shift. He’s every grumbling grandfather, and every dyspeptic uncle round the Christmas dinner table.

But, Father Christmas reassures the child reader, these gruff characters aren’t cross with us. Father Christmas may curse the rain, but he still struggles through it to bring the presents. He cares about doing his job properly, visiting every child in every domicile, from caravan to palace. And he still, for all the rain and drudgery and effort, leans out from the panel to personally wish us a ‘Happy Bloomin’ Christmas’ at the end.

Tobias is laid up in bed with the ‘flu and has unwisely left the formatting of this email to Rowan, which gives me an opportunity to commend to you one of his best Christmas Stories. ‘An All Too Magical Christmas’ is the tale of a middle-ranking government magician who takes the Christmas duty rota in the City of London hoping for a quiet bit of overtime but — like a social media intern left in charge of the corporate X account — becomes catastrophically overwhelmed by a chaotic eruption of malignant ancient Magick. Features trolls, geese, Puss in Boots, Herne’s Hunt on fixed-pedal bikes, an enchanted miniature toyshop, and some splendidly confused nutcracker soldiers.

Absolutely lovely piece and such great commentary on the innovations Briggs uses. And I never knew he used those wonderful Caran d'Ache pencils!

Every frame from this book and its sequel, “Father Christmas Goes On Holiday”, are etched into my memory. Thank you for distilling just how much they’re designed for children’s delight.