Corporate ukulele

🎶 You should see the things I see, when I'm selling pensions🎵

We once had a client – a global drinks manufacturer – who wanted to make a series of videos. They got a lot of questions from customers, they said, about the ingredients in their drinks. Some explainer animations would give them some quick and interesting answers to the most common questions.

Except, as it turned out, they weren’t sure. They weren’t sure they wanted to be interesting, they weren’t sure they wanted to explain anything, they weren’t sure they wanted to commit to anything that might look like actual information.

What they were sure about was the background music. They wanted something cheerful, something breezy. Some stomping, some clapping. Maybe a marimba, possibly a glockenspiel, probably some whistling. Definitely a ukulele.

It’s the universal musical choice of an organisation that has nothing to say and a tricky brand to not say it about. Upbeat, but not too humorous; handmade, but not actively weird; personable, but not too obvious. Not too individual or distinctive, a generic cheery wave of a sound.

Possibly irritatingly cheery.

The ukulele has its origins in small, nineteenth century European guitars, but had its first moment via Hawaii and a craze for Pacific themed novelty songs. Thereafter it has come and gone in waves of popularity, most notably after the Great Depression and then again in the wake of World War II.

Both of which give us a clue to its most recent resurgence:

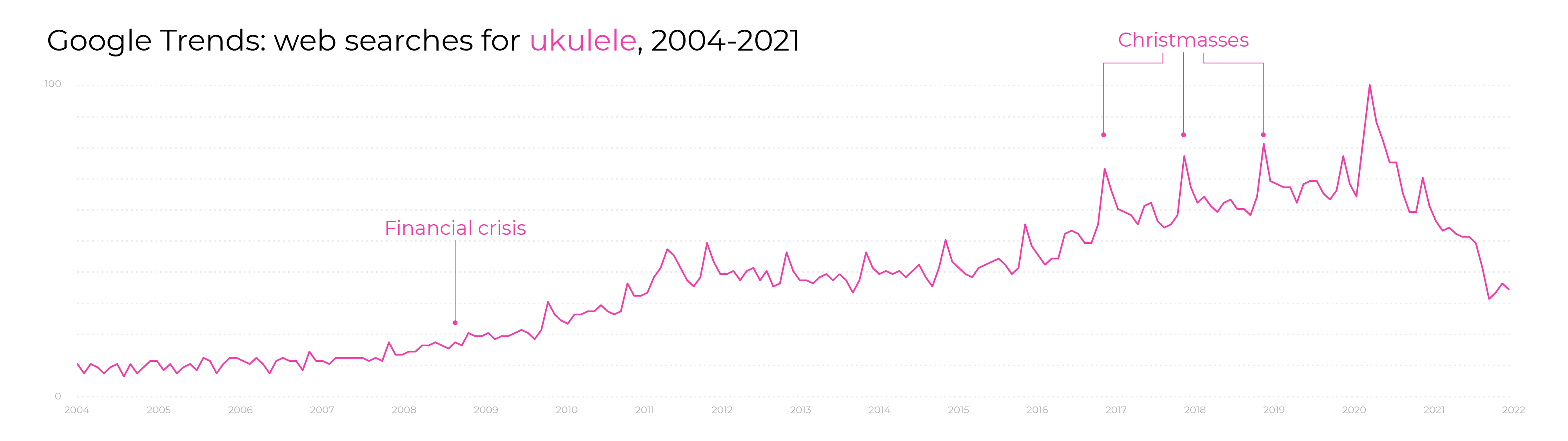

The ukulele reappears following the 2008 global financial crisis, the perfect instrument to soundtrack the implosion of twenty-first century capitalism.

There is a fundamental dissonance here: the cheerful, individual sound of the ukulele as an accompaniment to a global system of capital so byzantine and abstruse that apparently not even the people running it understood it. These were bankers, capitalist in tooth and claw, trading away other people’s homes and futures, not sitting in some sun-dappled glade wearing a chaplet of hedgerow blooms, plinking at a tuppenny guitar.

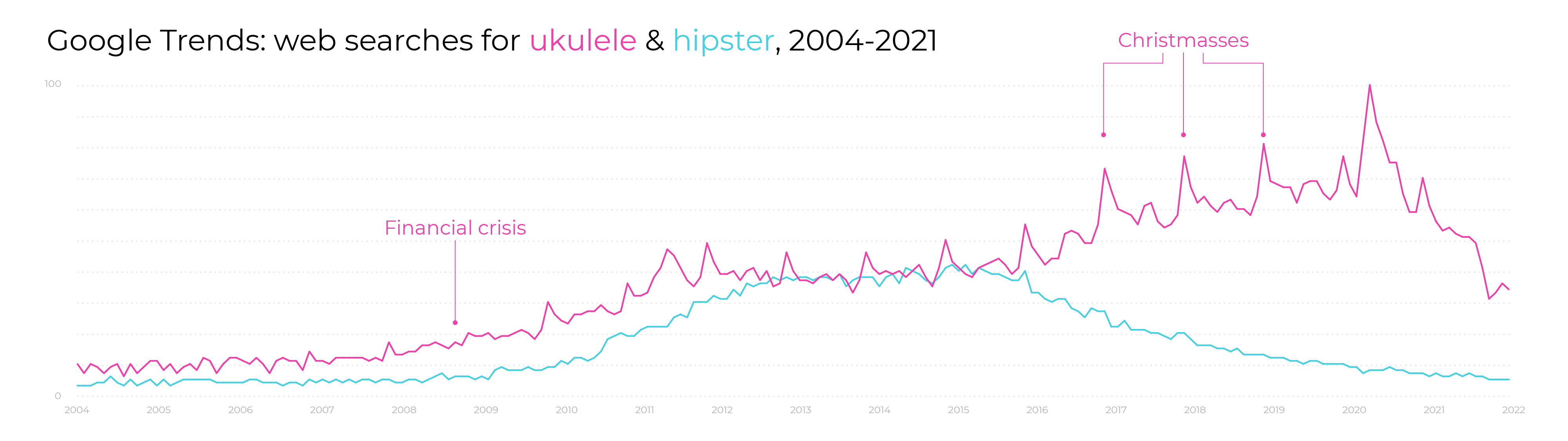

Mind you, it wasn’t the bankers who brought it back – the sole thing of which they’re innocent. It was the hipsters, pedalling in on their nineteenth century bikes, with their updated nineteenth century facial hair and refurbished nineteenth century warehouse studios, brandishing nineteenth century stringed instruments.

And here is another dissonance. Part of what annoyed people about that post-crisis generation of hipsters (apart from what usually annoys people about hipsters: they are young, innovative and apparently having fun) was that this was a moneyed, urban elite touting a cod-vintage artisanal ethic in the face of a resolutely technological and complex disaster that had destroyed livelihoods all over the world.

And the ukulele was complicit in that: Noah and the Whale, Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros, She & Him – happy carefree music in a world that was very unhappy and plenty of cares.

Of course, that dissonance was the point. Finance is technological and complex. It is simultaneously boring, exhausting and anxiety-producing. Of course financial institutions were going to reach for the reassuring, personal music of the ukulele.

And surrounded by such incomprehensible calamity, who wouldn’t want something as simple as a ukulele? Something simple to understand, simple to carry about, simple to use.

Like an iPhone.

The iPhone was launched at almost exactly the moment the ukulele returned to general consciousness and just as quickly became identified with the hipsters, at least at first.

Another dissonance: while it may initially seem similar – portable, personal, popular – the iPhone is, in many ways, the antithesis of the ukulele. Where the ukulele is of the moment, the phone remembers everything; where one is domestic, the other is global. The iPhone is user-friendly and packed with applications, simple though it may be; the ukulele is still a musical instrument that takes practice, craft and, if you’re lucky, talent.

And yet through this dissonance the two are inextricably linked. The ukulele, after all, is back:

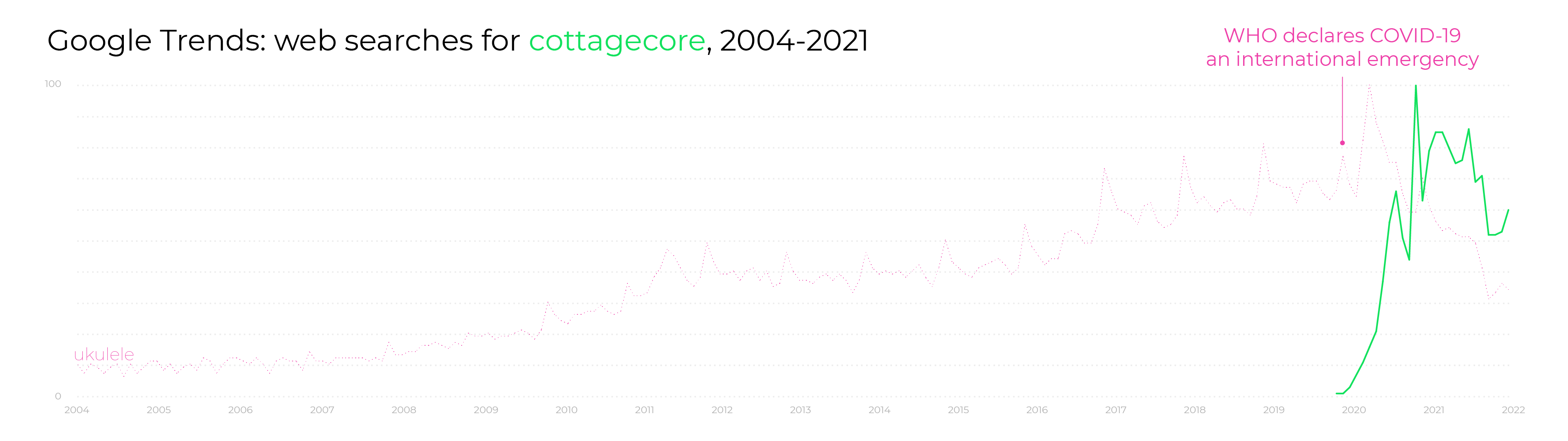

Locked in their homes for two years of global pandemic, people wanted some more reassuring, simple entertainment, and there on shelf, from a couple of Christmasses ago, was the ukulele.

And not just the ukulele. Sourdough starters and sea shanties. Knitting and boardgames and puppies. A new world of old pastimes.

And all of this is happening virtually, through video chat and social media. Instagram fantasies of rural life and Tik Tok tutorials on tuning and ukulele.

There’s nothing strange about living out a fantasy of a unconnected, local life on globally network social media, any more than there’s something strange about financial institutions trying to reassure us with their jaunty whistling TV ads.

We need that reassurance and we need that respite precisely because the world in our phones is so complex and overwhelming. The ukulele is our alternative, our escape. The dissonance is the point.

I would still like clients to stop requesting it, though.

Next week: the (gender) politics of dancing. The politics of, ooh, feeling good.