Bimbo eruption

SPOILER WARNING for Primary Colors (the novel and the film)

I reckon there are two things all Gen Xers remember about Monica Lewinsky: that she wore a beret while shaking Bill Clinton’s hand in a line-up, and that she owned a Gap dress that still bore the presidential seal of approval when she put it back in the wardrobe.

The ‘Gap’ label had semiotic weight. It had arrived in the UK at the end of the ‘80s blazoning clean, Benetton-style images of white backgrounds and ethnically diverse models. It was a little bit smart, a little bit different, a little bit pricey; somewhere you might go on pay day, or in the sales. In 1998 — when we first heard the name ‘Monica Lewinsky’ — it was still a reasonably fresh, aspirational brand. It felt very, very American, in a way that made its clothes difficult to parse (Are putty-coloured chinos cool? These guys seem to think they are.) But ‘American’, as a fashion vibe, was more desirable than it had been in the ‘80s. I had a Gap top with crossover spaghetti-straps of such baffling complexity that I briefly throttled myself every time I put it on.

If you were in your early 20s in the 1990s and had landed a starter-level job somewhere exciting, you might well have treated yourself to a Gap shift dress in celebration. Professional, ‘decent’, but slyly sexy; workwear that made people think ‘Audrey Hepburn’, not ‘Susan from accounts’. The kind of thing that probably costs a bit more than you can afford, and nevertheless probably doesn’t fit brilliantly, because in the scheme of things this is still cheaply-made clothing. But you’re 22; you look better in it than a 40 year old looks in Vivienne Westwood. You’ll cope.

These days, of course, Gap is where you go if you don’t have the nouse to go to Uniqlo or Cos. And the fact that Lewinsky was stitched up like a kipper in a Gap dress that she couldn’t afford to have dry-cleaned… man, that’s poignant. Like a Kids from Fame! LP in the rain.

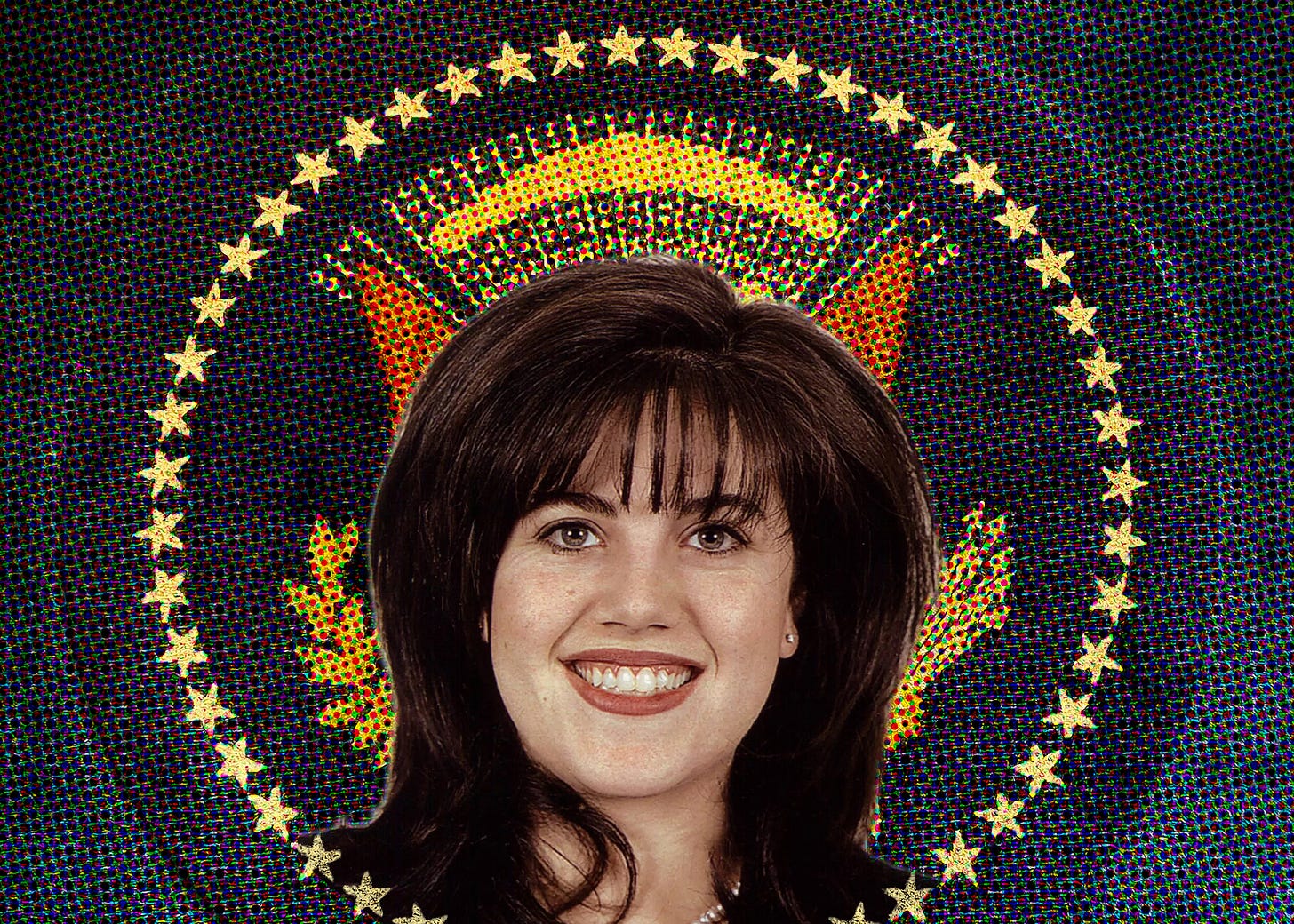

I think about Monica Lewinsky quite a lot; I suspect a lot of Gen X feminists do. It was a public fight between an incredibly powerful old man and a junior female staffer of our own age, and most of us called it wrong. But I think about her not so much because our feminist power-analysis was off, but because we were nasty about her. We smirked at her hairspray, her weight, her clothes, her make-up, her eager-beaver toothy smile. We didn’t only fail to recognise the not-so-subtle misogyny; we participated in it. We flubbed the ‘basic solidarity’ test. We thought she was a silly slut, and that she was destroying Clinton — the first Democrat president of our adult lifetimes — out of spite. We were mean, as well as wrong. Our instincts were to make it personal.

It’s hard to take a principled stand when the relevant conceptual premises are all tangled up with your real, everyday life. (This is a general problem with feminism.) I’m roughly the same age as Lewinsky, and when I first heard her name I knew plenty of women my age who were shagging their married bosses. They made me angry; the bosses, yes, but also the young women. They thought fucking the boss was an enviable achievement, and so did I. I thought it was mucky and immoral to cause that much pain to wives and children, but I also saw the procurement of male sexual attention as a competition. And a boss who had chosen to screw my colleague was a boss who had chosen not to screw me.

I like to think that I wouldn’t have shagged a married boss, although my opinions about these things were more about personal morality than they were about structural power. And anyway, none of them ever asked me to, so who knows? My more immediate problem was that I couldn’t incite a man to be so cruel and reckless, and it felt like a judgement on my lack of sexual distinction.

As Hanif Kureishi wrote in the year the ‘Lewinsky scandal’ broke, ‘There are some fucks for which a person would have their partner and children drown in a freezing sea.’ (‘Person’, eh? Pull the other one.) It’s not clear whether this is ‘fucks’ as in acts, or ‘fucks’ as in person-who-fucks; but whichever it was, it was, like, totally aspirational. I heard Kureishi’s line at the time because there was a lot of fuss about it, perhaps more than he had expected. It was a gleefully destructive obscenity of the kind that is thought awfully clever; but it also spears an actually-existing phenomenon, which is why it made so many people so angry. Adrift in this miasma of addled bollocks, I had one fixed point of concrete knowledge: I wasn’t the kind of woman for whom any man would risk his marriage, let alone watch his children drown. And I felt kind of second-rate about it.

This is what I mean about analytical premises getting tangled up with your real life. When these boss-fucking women dragged me into pub corners, a bottle of wine down and bursting to tell, they glittered. They had all the distinctive marks of a ‘promising young woman’: thin, clever, pretty, determined, quick, charismatic, a little bit dangerous. It did feel a lot like a competition, and they did seem empowered. They all made quicker progress in their careers than I did, and in the next ten years or so they will have the pensions to show for it. After all, they conducted pay-and-progression negotiations with someone who was naked, post-coital and had suddenly remembered that he quite enjoyed spending time with his kids. When the boss dumped them unceremoniously; when people around the office started to laugh at them; when they had to find a new job in a hurry because he wasn’t going to… When everything, eventually, came crashing down around their ears, as these things tend to do, it was hard to see them as women who required my feminist solidarity. They certainly hadn’t seemed very interested in it last time I’d checked.

And then Monica Lewinsky came along and I thought: why is she making such a bloody fuss? Silly cow.

Most recently I’ve been thinking about Lewinsky while re-reading Primary Colors (1996), the gossipy novelisation of Bill Clinton’s first presidential campaign. Primary Colors s one of those novels that is so close to real life that the reader has no way of knowing where the facts end and the fiction begins; Clinton is not even remotely disguised as Jack Stanton, a white governor from a southern US state running an outsider campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination. It was published anonymously, which was a terrific wheeze; but it would have been an enormous smash in any circumstances, because it’s highly enjoyable, well-drawn and tightly plotted.

There’s no Lewinsky avatar in Primary Colors; it was published before her affair with Clinton became public, and it covers the period before Stanton/Clinton entered the White House. Nevertheless, the candidate’s ‘bimbo eruption’ problem is at the heart of the book. Stanton’s staff are aware that their candidate keeps having one-off assignations in hotel rooms between campaign stops. But these incidents don’t qualify as ‘affairs’, nor (wearing our 1990s goggles) do there seem to be any troubling questions of consent. (Unlike Clinton’s real-life presidential campaign, none of the women accuse Stanton of abuse.) When the skeletons in Stanton’s boudoir are more ruthlessly interrogated, though, it turns out there is something worse: a ‘deeply, lusciously adolescent’ girl who says Stanton is the father of her unborn child. Even more serious — it is implied — is that this girl is the daughter of a Black restaurateur who is one of Stanton’s friends. The combination of age, ethnicity, pregnancy and friendship makes this a deadly political threat, and something must be done to find out whether her accusation is true.

The term ‘bimbo eruption’ is deeply redolent of the late ‘90s. It gave us a collective noun for all the big-haired, over-made-up, unclassy women who went public with accusations about Clinton’s behaviour. Like Kureishi’s line, it was cruel, funny and seemed to describe something real, something we could all see happening. It named a phenomenon, channelled a public intuition, and told us who to laugh at (and who to laugh with); it was a drive-by insult and a good joke; it was a highly effective piece of political comms.

So here’s the thing: ‘bimbo eruption’ was coined by Betsey Wright, the deputy chair of Clinton’s first presidential campaign. And Wright was not only a long-time Clinton devotee; she was a staunch advocate for women’s causes. She was the model for Primary Colors’ Libby Holden, the stroppy feminist activist who uncovers Stanton’s criminality and refuses to back down (Kathy Bates in the film; astonishingly great).

Wright remained loyal to Clinton through decades of revelations about his sexual affairs; ‘bimbo eruption’ was just the peak of her public prominence. It was Wright who warned Clinton not to run for the Arkansas governorship until he had a strategy for dealing with all the women who said he’d screwed them. Throughout his first presidential campaign she defended him against all-comers. In 1994 Time called her his ‘chief squelcher of controversy and scandal’, a role she was able to perform precisely because she knew so much of the truth, and because journalists found it hard to believe that a feminist — and a long-time close friend of Hillary — would stand by Bill if he had done the things he was accused of. She did not go with Clinton into the White House; her messy, ‘emotional’ professional style was enough to see her categorised as ‘not ready for prime time.’ (Funny, the things that are and are not considered disqualifying.) But in public at least, she kept her counsel as Kenneth Starr pursued Bill Clinton through seemingly endless tortuous legal procedures. Perhaps, like most left-aligned or ‘progressive’ activists, she thought it was all a radically right-wing Republican tactic to destroy a successful Democrat president.

We all thought that. Joe Klein, the Democrat-aligned journalist who wrote Primary Colors, still thinks it. In an afterword to the novel written in 2006, he dismisses the ‘Lewinsky insanity’ and asserts that Clinton’s political genius and performance in office excuses behaviour that was harmless, if faithless; ‘I remain convinced that his presidency will be judged far better in history than the reputations of those who attacked him so mercilessly and trivially.’ But then, Klein these days is to be found on Substack advising Democrats to be ‘less feminised’. I’m not really sure what that means. In office, Clinton required employers to allow (unpaid) pregnancy leave, and shored up family planning programmes. Was that enough to justify placing a man of dubious sexual morality in the White House? Those were the real-world choices.

Who knows what to make of Wright’s story? In Primary Colors, when Holden reaches the final, rotten bottom of Stanton’s amorality, she kills herself rather than choose between covering for him and going to the press. The fictional arc of Libby Holden — an adamantine, copper-bottomed Second Wave feminist defending a powerful man who, at best, exploits his position — could end only in self-murder; the dissonance was real, and even Klein didn’t know how to handle it. Wright, though, preferred to go on. A longstanding campaigner against the death penalty, in 2009 she was accused of smuggling ‘a knife, tweezers, a boxcutter, and 48 tattoo needles’ into prison while visiting an inmate awaiting execution. Most of the charges were dismissed, but it’s kind of a magnificent rap sheet.

If you’re not the sort of woman who fucks the boss, then you just might be <shudder> a good girl.

This is a great essay and expresses really well so many of the contradictions of internalised misogyny that I’m still trying to come to terms with at 50 years of age!