To London for a meeting, but I made time beforehand to visit Lambeth Palace Library to see Unfolding Time, a small but exquisite exhibition of medieval pockets calendars, almanacs and time keeping accessories.

I went largely in my real world identity as an information designer and I was not disappointed. The objects on display were mostly paper pocket calendars, complex documents of timelines and matrices that helped medieval people keep track of saints’ days, moveable feasts and sometimes just what day of the week it was.

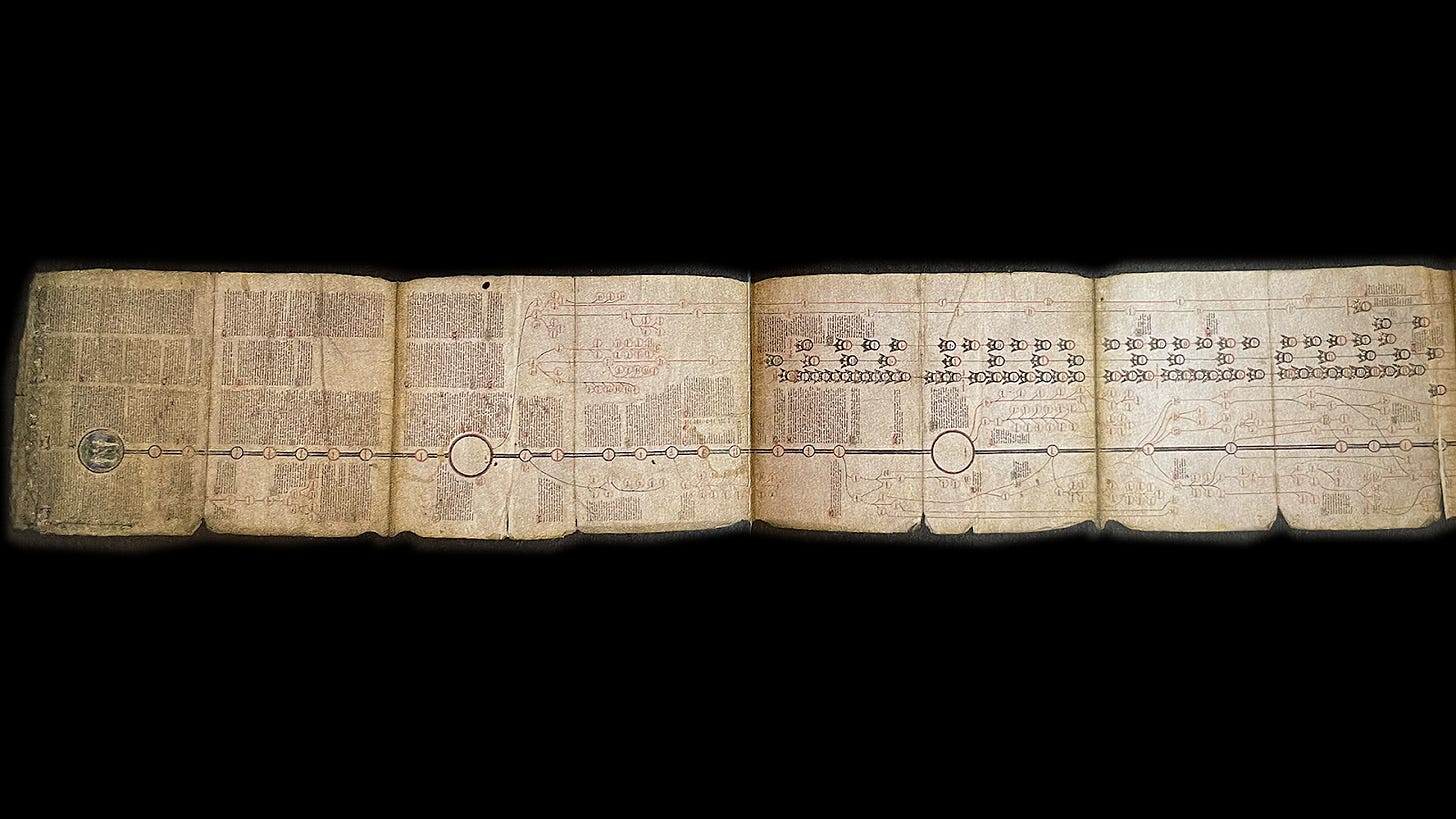

As the title of the exhibition suggests, the books themselves were extraordinary objects, cleverly folded and pleated to tuck long timelines and almanacks into tiny books that would fit in a pocket. But their contents were even more extraordinary.

There was beautiful data visualisation, as in this table of months, showing the tasks suitable for each month, coupled with an infographic showing the hours of daylight: the red lines in each disc are day time, the black, hours of night. You’ll note that the proper activity for May is collecting flowers.

Then there was fantastic paper engineering, as in this volvelle:

A volvelle is circular layers of card stacked up on top of each other and pinned in the centre so that they can each rotate independently. The circles on top have holes or pointers cut into them so that as they rotate they reveal elements of the circle beneath.

I love volvelles. One of the highlights of my career so far is persuading Google to make one as a marketing exercise. How delightful to have a twenty-first century digital company indulging in medieval paper engineering.

This one was particularly splendid for having a hole which revealed phases of the moon. The moon, of course, as a grumpy little blue face, like a character from The Mighty Boosh.

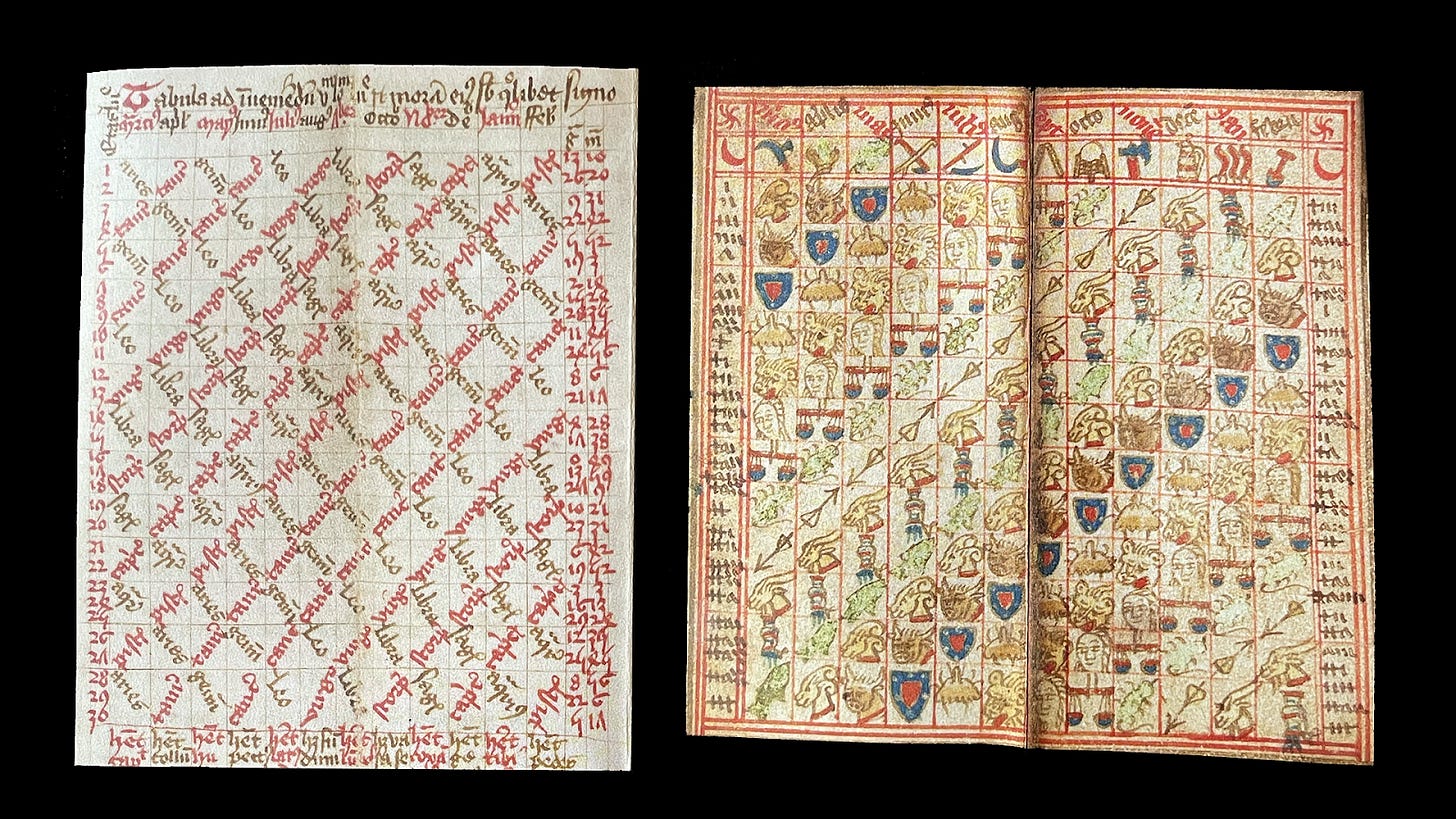

Then there were extraordinary pieces of text art, like this matrix for determining the star sign for each month (and a lovely iconographic version next to it):

The exhibition was wonderful, but small, and I found myself still early for my meeting, so I wandered to it by way of Tate Britain, where I saw this, ‘The Arrival’ by Christopher Nevinson (c. 1913):

Having just come from the medieval calendars, this really made me stop and think.

Most of those medieval calendars were intended to be perpetual, not for one year but eternally useful. And they meant eternally. Right up to the end of the world, which was presumably, hopefully, imminent.

These calendars placed the present within an eternal pattern. Not just the reliable cycle of feast days and seasons, but within a divine history, frequently including timelines that went all the way back to the Biblical creation of the world:

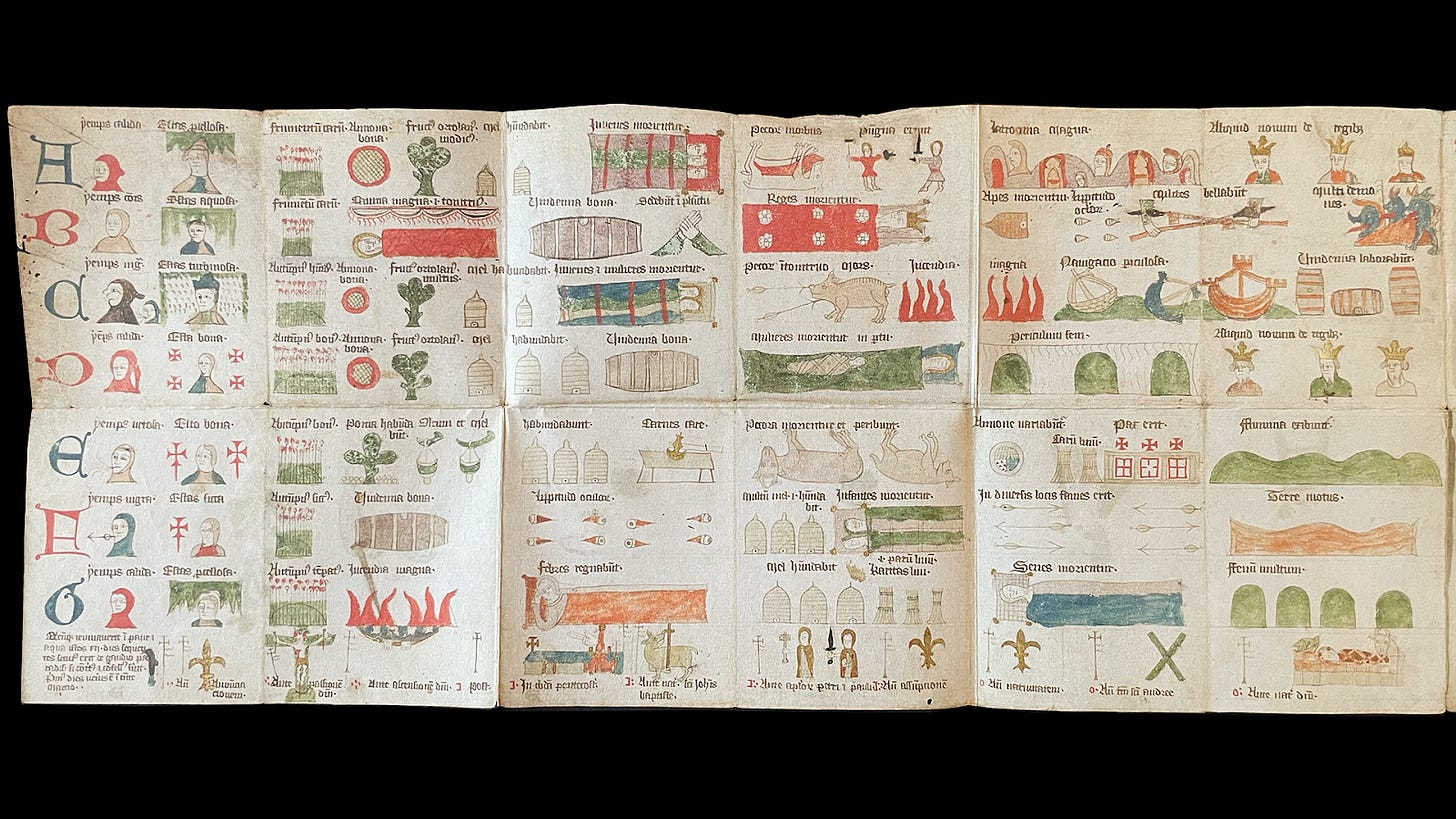

And they also went forward, often featuring means of foretelling the future. Depending on the dominical letter of a year, the wine harvest will be good, the king will die, it’ll be a good time to treat eye diseases:

These calendars situated the user in a predictable, ordained mechanism of time, in which the past, present and future were all parts of a divine process.

The modernist painting, on the other hand, anatomises the moment. Nevinson was interested in ‘simultaneity’, the way that our experience of the world is made from multiple elements, the eye saccading, the brain piecing together a gestalt from the different senses.

On the other hand it could be seen as a vision of individual experience, the way a moment can be experienced in multiple different ways by different people. No moment is definitive but only exists in the eyes of the beholders.

The comparison between the two depictions of time really struck me, the intervening changes in technology, which increasingly mechanised our sense of time, of culture, in which labour, communication and connectedness demanded a new conception of the present, and the changes in the idea of the self in relation to society. How the medieval depiction of the now in the universal and eternal had become the infinite, individual present.

It also reminded me that I need to go to galleries more often.

The Metropolitan visits art galleries all too infrequently:

Nice indeed. I think there is a historical narrative to it. It's all about ordering the world (what we perceive as the world) and what we loose by ordering it. The medieval pieces help to provide temporal order, fixing the past and even predicting the future, thereby annihalating the present and all the dangers and uncertainties it brings. Absolutely necessary for survival in medieval times. The arrival tells you that you are missing something when ordering everything. The multiple presents, the uncertain past, and daunting, but exciting future, once you arrived. But might well lead you into madness... and that indeed came shortly after 1913.

I love this sort of thing—it has a "spreadsheets of the past" kind of vibe to it that pleases both my left and right brains.

This also reminds me that I have a small collection of optical toys (including stereoscopes, thaumatropes, and a zoetrope) that I don't get out often enough.